[book] Python Data Science Handbook

A study note of [1]

1. Numpy

Data types in Python 🐍

-

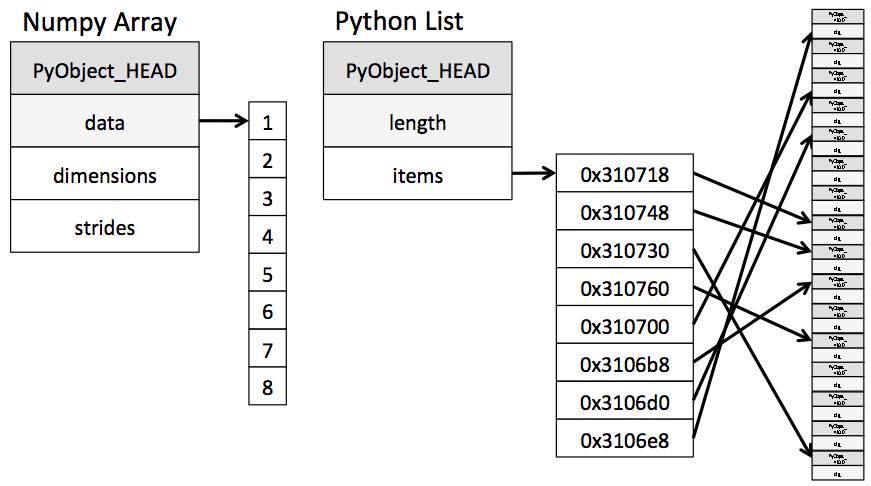

Fixed-type NumPy-style arrays lack this flexibility, but are much more efficient for storing and manipulating data.

-

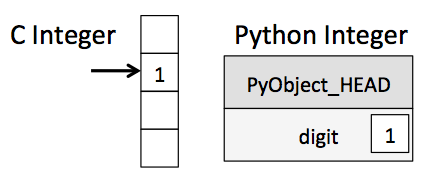

The standard Python implementation is written in C. This means that every Python object is simply a cleverly-disguised C structure, which contains not only its value, but other information as well.

-

A Python integer is a pointer to a position in memory containing all the Python object information, including the bytes that contain the integer value. This extra information in the Python integer structure is what allows Python to be coded so freely and dynamically. All this additional information in Python types comes at a cost, however, which becomes especially apparent in structures that combine many of these objects.

-

Much more useful, however, is the

ndarrayobject of the NumPy package. While Python's array object provides efficient storage of array-based data, NumPy adds to this efficient operations on that data.

Basics of NumPy arrays

TOC

- np arrary attributes: dimension, shape, size, dtype, itemsize, etc.

- Array indexing: Accessing Single Elements

- Array Slicing: Accessing Subarrays

- one-dimensional array

- multi-dimensional

- Reshaping of Arrays

- Array Concatenation and Splitting

- The NumPy slicing syntax follows that of the standard Python list; to access a slice of an array x, use this:

x[start:stop:step]

-

If any of these are unspecified, they default to the values start=0, stop=size of dimension, step=1.

-

Other attributes include

itemsize, which lists the size (in bytes) of each array element, andnbytes, which lists the total size (in bytes) of the array -

In a multi-dimensional array, items can be accessed using a comma-separated tuple of indices:

x2

>>> array([[3, 5, 2, 4],

[7, 6, 8, 8],

[1, 6, 7, 7]])

x2[0, 0]

>>> 3

-

In slicing, a potentially confusing case is when the step value is negative. In this case, the defaults for start and stop are swapped. This becomes a convenient way to reverse an array. (便捷地反转一个array的方法)

-

Keep in mind that, unlike Python lists, NumPy arrays have a fixed type. This means, for example, that if you attempt to insert a floating-point value to an integer array, the value will be silently truncated.

-

One important–and extremely useful–thing to know about array slices is that they return views rather than copies of the array data. This is one area in which NumPy array slicing differs from Python list slicing: in lists, slices will be copies.

-

If we modify the subarray, we'll see that the original array is changed! This default behavior is actually quite useful: it means that when we work with large datasets, we can access and process pieces of these datasets without the need to copy the underlying data buffer.

-

In the case of row access, the empty slice can be omitted for a more compact syntax:

print(x2[0]) # equivalent to x2[0, :]

- Another common reshaping pattern is the conversion of a one-dimensional array into a two-dimensional row or column matrix. This can be done with the reshape method, or more easily done by making use of the newaxis keyword within a slice operation:

x = np.array([1, 2, 3])

# row vector via reshape

x.reshape((1, 3))

# row vector via newaxis

x[np.newaxis, :]

Computation on NumPy Arrays: Universal Functions

TOC

- The Slowness of Loops

- Introducing UFuncs

- Exploring NumPy's UFuncs

- Array arithmetic

- Absolute value

- Trigonometric functions

- Exponents and logarithms

- Specialized ufuncs

- Advanced Ufunc Features

- Specifying output

- Aggregates

- Outer products

- Ufuncs: Learning More

-

Vectorized operations in NumPy are implemented via ufuncs, whose main purpose is to quickly execute repeated operations on values in NumPy arrays. Ufuncs are extremely flexible – before we saw an operation between a scalar and an array, but we can also operate between two arrays

-

Ufuncs exist in two flavors: unary ufuncs, which operate on a single input, and binary ufuncs, which operate on two inputs.

-

Each of these arithmetic operations are simply convenient wrappers around specific functions built into NumPy

-

The following table lists the arithmetic operators implemented in NumPy:

| Operator | Equivalent ufunc | Description |

|---|---|---|

+ |

np.add |

Addition (e.g., 1 + 1 = 2) |

- |

np.subtract |

Subtraction (e.g., 3 - 2 = 1) |

- |

np.negative |

Unary negation (e.g., -2) |

* |

np.multiply |

Multiplication (e.g., 2 * 3 = 6) |

/ |

np.divide |

Division (e.g., 3 / 2 = 1.5) |

// |

np.floor_divide |

Floor division (e.g., 3 // 2 = 1) |

** |

np.power |

Exponentiation (e.g., 2 ** 3 = 8) |

% |

np.mod |

Modulus/remainder (e.g., 9 % 4 = 1) |

- There are also some specialized versions that are useful for maintaining precision with very small input:

x = [0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1]

print("exp(x) - 1 =", np.expm1(x))

print("log(1 + x) =", np.log1p(x))

>>> exp(x) - 1 = [ 0. 0.0010005 0.01005017 0.10517092]

>>> log(1 + x) = [ 0. 0.0009995 0.00995033 0.09531018]

When x is very small, these functions give more precise values than if the raw np.log or np.exp were to be used.

- Specifying the output:

y = np.zeros(10)

np.power(2, x, out=y[::2])

print(y)

>>> [ 1. 0. 2. 0. 4. 0. 8. 0. 16. 0.]

If we had instead written y[::2] = 2 ** x, this would have resulted in the creation of a temporary array to hold the results of 2 ** x, followed by a second operation copying those values into the y array. This doesn't make much of a difference for such a small computation, but for very large arrays the memory savings from careful use of the out argument can be significant.

-

Another excellent source for more specialized and obscure ufuncs is the submodule

scipy.special. If you want to compute some obscure mathematical function on your data, chances are it is implemented inscipy.special. -

The

ufunc.atandufunc.reduceatmethods, which we'll explore in Fancy Indexing, are very helpful as well. -

More information on universal functions (including the full list of available functions) can be found on the

NumPyandSciPydocumentation websites.

Aggregations: Min, Max, and Everything In Between

TOC

- Summing the Values in an Array

- Minimum and Maximum

- Multi dimensional aggregates

- Other aggregation functions

- For min, max, sum, and several other NumPy aggregates, a shorter syntax is to use methods of the array object itself:

print(big_array.min(), big_array.max(), big_array.sum())

-

The

axiskeyword specifies the dimension of the array that will be collapsed, rather than the dimension that will be returned. So specifyingaxis=0means that the first axis will be collapsed: for two-dimensional arrays, this means that values within each column will be aggregated. -

Most aggregates have a

NaN-safe counterpart that computes the result while ignoring missing values, which are marked by the special IEEE floating-point NaN value (for a fuller discussion of missing data, see Handling Missing Data).The following table provides a list of useful aggregation functions available inNumPy:

| Function Name | NaN-safe Version | Description |

|---|---|---|

| np.sum | np.nansum | Compute sum of elements |

| np.prod | np.nanprod | Compute product of elements |

| np.mean | np.nanmean | Compute mean of elements |

| np.std | np.nanstd | Compute standard deviation |

| np.var | np.nanvar | Compute variance |

| np.min | np.nanmin | Find minimum value |

| np.max | np.nanmax | Find maximum value |

| np.argmin | np.nanargmin | Find index of minimum value |

| np.argmax | np.nanargmax | Find index of maximum value |

| np.median | np.nanmedian | Compute median of elements |

| np.percentile | np.nanpercentile | Compute rank-based statistics of elements |

| np.any | N/A | Evaluate whether any elements are true |

| np.all | N/A | Evaluate whether all elements are true |

Computation on Arrays: Broadcasting

TOC

- Introducing Broadcasting

- Rules of Broadcasting

- Broadcasting examples 1/2/3

- Broadcasting in Practice

- Centering an array

- Plotting a two-dimensional function

-

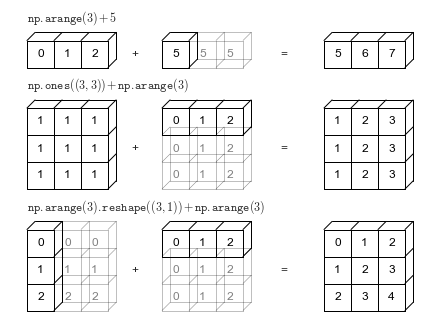

Broadcasting is simply a set of rules for applying binary ufuncs (e.g., addition, subtraction, multiplication, etc.) on arrays of different sizes.

-

For arrays of the same size, binary operations are performed on an element-by-element basis

-

The advantage of

NumPy's broadcasting is that this duplication of values does not actually take place, but it is a useful mental model as we think about broadcasting. -

Broadcasting in

NumPyfollows a strict set of rules to determine the interaction between the two arrays:- Rule 1: If the two arrays differ in their number of dimensions, the shape of the one with fewer dimensions is padded with ones on its leading (left) side.

- Rule 2: If the shape of the two arrays does not match in any dimension, the array with shape equal to 1 in that dimension is stretched to match the other shape.

- Rule 3: If in any dimension the sizes disagree and neither is equal to 1, an error is raised.

Comparisons, Masks, and Boolean Logic

TOC

- Example

- Comparison Operators as ufuncs

- Working with Boolean Arrays

- Counting entries

- Boolean operators

- Boolean Arrays as Masks

- Aside: Using the Keywords

and/orVersus the Operators&/|

-

A quick warning: as mentioned in Aggregations: Min, Max, and Everything In Between, Python has built-in

sum(),any(), andall()functions. These have a different syntax than theNumPyversions, and in particular will fail or produce unintended results when used on multidimensional arrays. Be sure that you are usingnp.sum(),np.any(), andnp.all()for these examples! -

When you use

andoror, it's equivalent to asking Python to treat the object as a single Boolean entity. So remember this:andandorperform a single Boolean evaluation on an entire object, while&and|perform multiple Boolean evaluations on the content (the individual bits or bytes) of an object. For BooleanNumPyarrays, the latter is nearly always the desired operation.

Fancy Indexing

TOC

- Exploring Fancy Indexing

- Combined Indexing

- Example: Selecting Random Points

- Modifying Values with Fancy Indexing

- Example: Binning Data

-

Fancy indexing is like the simple indexing we've already seen, but we pass arrays of indices in place of single scalars. This allows us to very quickly access and modify complicated subsets of an array's values.

-

When using fancy indexing, the shape of the result reflects the shape of the index arrays rather than the shape of the array being indexed:

ind = np.array([[3, 7],

[4, 5]])

x[ind]

>>> array([[71, 86],

[60, 20]])

-

It is always important to remember with fancy indexing that the return value reflects the broadcasted shape of the indices, rather than the shape of the array being indexed.

-

One common use of fancy indexing is the selection of subsets of rows from a matrix.

indices = np.random.choice(X.shape[0], 20, replace=False)

selection = X[indices] # fancy indexing here

selection.shape

>>> (20, 2)

print(x)

>>> [ 6. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

i = [2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4]

x[i] += 1

x

>>> array([ 6., 0., 1., 1., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.])

-

x[i] += 1is meant as a shorthand ofx[i] = x[i] + 1.x[i] + 1is evaluated, and then the result is assigned to the indices inx. With this in mind, it is not the augmentation that happens multiple times, but the assignment, which leads to the rather nonintuitive results. -

What if you want the other behavior where the operation is repeated? For this, you can use the

at()method of ufuncs (available since NumPy 1.8), and do the following:

i = [2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4]

x = np.zeros(10)

np.add.at(x, i, 1)

print(x)

>>> [ 0. 0. 1. 2. 3. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.]

- The pairing of indices in fancy indexing follows all the broadcasting rules that were mentioned in Computation on Arrays: Broadcasting.

Sorting Arrays

TOC

- Fast Sorting in

NumPy:np.sortandnp.argsort- Sorting along rows or columns

- Partial Sorts: Partitioning

- Example: k-Nearest Neighbors

- Aside: Big-O Notation

-

As any first-year computer science major will tell you, the selection sort is useful for its simplicity, but is much too slow to be useful for larger arrays. For a list of $N$ values, it requires $N$ loops, each of which does on order $\sim N$ comparisons to find the swap value. In terms of the "big-O" notation often used to characterize these algorithms (see Big-O Notation), selection sort averages $\mathcal{O}[N^2]$: if you double the number of items in the list, the execution time will go up by about a factor of four.

-

By default

np.sortuses an $\mathcal{O}[N \mathcal{log}N]$ , quicksort algorithm, though mergesort andheapsortare also available. For most applications, the default quicksort is more than sufficient. -

To return a sorted version of the array without modifying the input, you can use

np.sort

x = np.array([2, 1, 4, 3, 5])

np.sort(x)

>>> array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

- A related function is

argsort, which instead returns the indices of the sorted elements:

x = np.array([2, 1, 4, 3, 5])

i = np.argsort(x)

print(i)

>>> [1 0 3 2 4]

- If you prefer to sort the array in-place, you can instead use the sort method of arrays:

x.sort()

print(x)

>>> [1 2 3 4 5]

- Sometimes we're not interested in sorting the entire array, but simply want to find the k smallest values in the array.

NumPyprovides this in thenp.partitionfunction.np.partitiontakes an array and a number K; the result is a new array with the smallest K values to the left of the partition, and the remaining values to the right, in arbitrary order.

x = np.array([7, 2, 3, 1, 6, 5, 4])

np.partition(x, 3)

>>> array([2, 1, 3, 4, 6, 5, 7])

-

Big-O notation, in this loose sense, tells you how much time your algorithm will take as you increase the amount of data. If you have an $\mathcal{O}[N]$ (read "order $N$") algorithm that takes 1 second to operate on a list of length N=1,000, then you should expect it to take roughly 5 seconds for a list of length N=5,000. If you have an $\mathcal{O}[N^2]$ (read "order N squared") algorithm that takes 1 second for N=1000, then you should expect it to take about 25 seconds for N=5000.

-

Notice that the big-O notation by itself tells you nothing about the actual wall-clock time of a computation, but only about its scaling as you change N. Generally, for example, an $\mathcal{O}[N]$ algorithm is considered to have better scaling than an $\mathcal{O}[N^2]$ algorithm, and for good reason. But for small datasets in particular, the algorithm with better scaling might not be faster.

Structured Data: NumPy's Structured Arrays

less important - use more pandas instead of numpy structed array

TOC

- Creating Structured Arrays

- More Advanced Compound Types

- RecordArrays: Structured Arrays with a Twist

- On to Pandas

- The handy thing with structured arrays is that you can now refer to values either by index or by name

- If the names of the types do not matter to you, you can specify the types alone in a comma-separated string

np.dtype('S10,i4,f8')

>>> dtype([('f0', 'S10'), ('f1', '<i4'), ('f2', '<f8')])

- The shortened string format codes may seem confusing, but they are built on simple principles. The first (optional) character is

<or>, which means "little endian" or "big endian," respectively, and specifies the ordering convention for significant bits. The next character specifies the type of data: characters, bytes, ints, floating points, and so on (see the table below). The last character or characters represents the size of the object in bytes.

| Character | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 'b' | Byte | np.dtype('b') |

| 'i' | Signed integer | np.dtype('i4') == np.int32 |

| 'u' | Unsigned integer | np.dtype('u1') == np.uint8 |

| 'f' | Floating point | np.dtype('f8') == np.int64 |

| 'c' | Complex floating point | np.dtype('c16') == np.complex128 |

| 'S', 'a' | String | np.dtype('S5') |

| 'U' | Unicode string | np.dtype('U') == np.str_ |

| 'V' | Raw data (void) | np.dtype('V') == np.void |

2. Pandas 🐼

Introducing Pandas Objects

TOC

- The Pandas Series Object

Seriesas generalized NumPy arraySeriesas specialized dictionary- Constructing Series objects

- The Pandas DataFrame Object

- DataFrame as a generalized NumPy array

- DataFrame as specialized dictionary

- Constructing DataFrame objects

- From a single Series object

- From a list of dicts

- From a dictionary of Series objects

- From a two-dimensional NumPy array

- From a NumPy structured array

- The Pandas Index Object

- Index as immutable array

- Index as ordered set

-

A Pandas Series is a one-dimensional array of indexed data.

-

At the very basic level, Pandas objects can be thought of as enhanced versions of NumPy structured arrays in which the rows and columns are identified with labels rather than simple integer indices. (series as generalized Numpy array)

-

You can think of a Pandas Series a bit like a specialization of a Python dictionary. A dictionary is a structure that maps arbitrary keys to a set of arbitrary values, and a Series is a structure which maps typed keys to a set of typed values. This typing is important: just as the type-specific compiled code behind a NumPy array makes it more efficient than a Python list for certain operations, the type information of a Pandas Series makes it much more efficient than Python dictionaries for certain operations. (series as specilized dictionary)

-

Unlike a dictionary, though, the Series also supports array-style operations such as slicing (using its index)

-

It may look like the Series object is basically interchangeable with a one-dimensional NumPy array. The essential difference is the presence of the index: while the Numpy Array has an implicitly defined integer index used to access the values, the Pandas Series has an explicitly defined index associated with the values.

-

As we see in the output, the Series wraps both a sequence of values and a sequence of indices, which we can access with the values and index attributes. The values are simply a familiar NumPy array

-

The pandas Series

indexis an array-like object of typepd.Index

data.index

>>> RangeIndex(start=0, stop=4, step=1)

Data Indexing and Selection

TOC

- Data Selection in Series

- Series as dictionary

- Series as one-dimensional array

- Indexers: loc, iloc, and ix

- Data Selection in DataFrame

- DataFrame as a dictionary

- DataFrame as two-dimensional array

- Additional indexing conventions

-

There are a couple extra indexing conventions that might seem at odds with the preceding discussion, but nevertheless can be very useful in practice. First, while indexing refers to columns, slicing refers to rows

-

Pandas provides some special indexer attributes, these are not functional methods, but attributes that expose a particular slicing interface to the data in the Series.

-

the

locattribute allows indexing and slicing that always references the explicit index, this means explicit index and column names in DataFrames. -

The

ilocattribute allows indexing and slicing that always references the implicit Python-style index -

A third indexing attribute, ix, is a hybrid of the two, and for Series objects is equivalent to standard []-based indexing. The purpose of the ix indexer will become more apparent in the context of DataFrame objects, where both implicit index or expilcit index and column name can be used.

data = pd.Series(['a', 'b', 'c'], index=[1, 3, 5])

data

>>>

1 a

3 b

5 c

dtype: object

data.loc[1]

>>> 'a'

data.iloc[1]

>>> 'b'

-

One guiding principle of Python code is that "explicit is better than implicit." The explicit nature of

locandilocmake them very useful in maintaining clean and readable code -

a DataFrame acts in many ways like a two-dimensional or structured array, and in other ways like a dictionary of Series structures sharing the same index. These analogies can be helpful to keep in mind as we explore data selection within this structure.

-

we can use attribute-style access with column names that are strings

data.area

>>>

California 423967

Florida 170312

Illinois 149995

New York 141297

Texas 695662

Name: area, dtype: int64

- Avoid the temptation to try column assignment via attribute (i.e., use data['pop'] = z rather than data.pop = z)

Operating on Data in Pandas

TOC

- Ufuncs: Index Preservation

- UFuncs: Index Alignment

- Index alignment in Series

- Index alignment in DataFrame

- Ufuncs: Operations Between DataFrame and Series

-

Pandas includes a couple useful twists, however: for unary operations like negation and trigonometric functions, these ufuncs will preserve index and column labels in the output, and for binary operations such as addition and multiplication, Pandas will automatically align indices when passing the objects to the ufunc.

-

For binary operations on two Series or DataFrame objects, Pandas will align indices in the process of performing the operation. This is very convenient when working with incomplete data

-

Any item for which one or the other does not have an entry is marked with

NaN, or "Not a Number," which is how Pandas marks missing data (see further discussion of missing data in Handling Missing Data). This index matching is implemented this way for any of Python's built-in arithmetic expressions; any missing values are filled in withNaNby default -

If using

NaNvalues is not the desired behavior, the fill value can be modified using appropriate object methods in place of the operators.

A.add(B, fill_value=0)

>>>

0 2.0

1 5.0

2 9.0

3 5.0

dtype: float64

- This preservation and alignment of indices and columns means that operations on data in Pandas will always maintain the data context, which prevents the types of silly errors that might come up when working with heterogeneous and/or misaligned data in raw NumPy arrays.

Handling Missing Data

TOC

- Trade-Offs in Missing Data Conventions

- Missing Data in Pandas

None: Pythonic missing dataNaN: Missing numerical data- NaN and None in Pandas

- Operating on Null Values

- Detecting null values

- Dropping null values

- Filling null values

-

With these constraints in mind, Pandas chose to use sentinels for missing data, and further chose to use two already-existing Python

nullvalues: the special floating-pointNaNvalue, and the Python None object. This choice has some side effects, as we will see, but in practice ends up being a good compromise in most cases of interest. -

The way in which Pandas handles missing values is constrained by its reliance on the NumPy package, which does not have a built-in notion of

NAvalues for non-floating-point data types. -

Because it is a Python object,

Nonecannot be used in any arbitrary NumPy/Pandas array, but only in arrays with data type 'object' (i.e., arrays of Python objects)

vals1 = np.array([1, None, 3, 4])

vals1

>>> array([1, None, 3, 4], dtype=object)

This dtype=object means that the best common type representation NumPy could infer for the contents of the array is that they are Python objects. While this kind of object array is useful for some purposes, any operations on the data will be done at the Python level, with much more overhead than the typically fast operations seen for arrays with native types.

-

The use of Python objects in an array also means that if you perform aggregations like

sum()ormin()across an array with aNonevalue, you will generally get an error -

The following table lists the upcasting conventions in Pandas when NA values are introduced:

| Typeclass | Conversion When Storing NAs | NA Sentinel Value |

|---|---|---|

floating |

No change | np.nan |

object |

No change | None or np.nan |

integer |

Cast to float64 |

np.nan |

boolean |

Cast to object | None or np.nan |

-

Keep in mind that in Pandas, string data is always stored with an

objectdtype. -

The other missing data representation,

NaN(acronym for Not a Number), is different; it is a special floating-point value recognized by all systems that use the standard IEEE floating-point representation

vals2 = np.array([1, np.nan, 3, 4])

vals2.dtype

>>> dtype('float64')

-

Notice that NumPy chose a native floating-point type for this array: this means that unlike the object array from before, this array supports fast operations pushed into compiled code. You should be aware that

NaNis a bit like a data virus–it infects any other object it touches. -

Keep in mind that

NaNis specifically a floating-point value; there is no equivalentNaNvalue for integers, strings, or other types. -

Pandas treats

NoneandNaNas essentially interchangeable for indicating missing or null values. To facilitate this convention, there are several useful methods for detecting, removing, and replacingnullvalues in Pandas data structures.isnull(): Generate a boolean mask indicating missing valuesnotnull(): Opposite ofisnull()dropna(): Return a filtered version of the datafillna(): Return a copy of the data with missing values filled or imputed

-

- In addition to the masking used before, there are the convenience methods, dropna() (which removes NA values) and fillna() (which fills in NA values)

-

By default, dropna() will drop all rows in which any null value is present; you might rather be interested in dropping rows or columns with all

NAvalues, or a majority ofNAvalues. This can be specified through the how or thresh parameters, which allow fine control of the number of nulls to allow through.

df.dropna(axis='columns', how='all')

df.dropna(axis='rows', thresh=3)

Hierarchical Indexing

TOC

- A Multiply Indexed Series

- The bad way

- The Better Way: Pandas MultiIndex

- MultiIndex as extra dimension

- Methods of MultiIndex Creation

- Explicit MultiIndex constructors

- MultiIndex level names

- MultiIndex for columns

- Indexing and Slicing a MultiIndex

- Multiply indexed Series

- Multiply indexed DataFrames

- Rearranging Multi-Indices

- Sorted and unsorted indices

- Stacking and unstacking indices

- Index setting and resetting

- Data Aggregations on Multi-Indices

- Aside: Panel Data

-

While Pandas does provide

PanelandPanel4Dobjects that natively handle three-dimensional and four-dimensional data (see Aside: Panel Data), a far more common pattern in practice is to make use of hierarchical indexing (also known as multi-indexing) to incorporate multiple index levels within a single index. In this way, higher-dimensional data can be compactly represented within the familiar one-dimensional Series and two-dimensional DataFrame objects. -

The most straightforward way to construct a multiply indexed Series or DataFrame is to simply pass a list of two or more index arrays to the constructor.

-

Pandas is built with this equivalence in mind. The unstack() method will quickly convert a multiply indexed Series into a conventionally indexed DataFrame and naturally, the stack() method provides the opposite operation

pop_df = pop.unstack()

pop = pop_df.stack()

- Seeing this, you might wonder why would we would bother with hierarchical indexing at all. The reason is simple: just as we were able to use multi-indexing to represent two-dimensional data within a one-dimensional Series, we can also use it to represent data of three or more dimensions in a Series or DataFrame. Each extra level in a multi-index represents an extra dimension of data; taking advantage of this property gives us much more flexibility in the types of data we can represent.

df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.rand(4, 2),

index=[['a', 'a', 'b', 'b'], [1, 2, 1, 2]],

columns=['data1', 'data2'])

df

| data1 | data2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | 1 | 0.554233 | 0.356072 |

| 2 | 0.925244 | 0.219474 | |

| b | 1 | 0.441759 | 0.610054 |

| 2 | 0.171495 | 0.886688 |

- The work of creating the MultiIndex is done in the background. Similarly, if you pass a dictionary with appropriate tuples as keys, Pandas will automatically recognize this and use a

MultiIndexby default:

data = {('California', 2000): 33871648,

('California', 2010): 37253956,

('Texas', 2000): 20851820,

('Texas', 2010): 25145561,

('New York', 2000): 18976457,

('New York', 2010): 19378102}

pd.Series(data)

>>>

California 2000 33871648

2010 37253956

New York 2000 18976457

2010 19378102

Texas 2000 20851820

2010 25145561

dtype: int64

- For more flexibility in how the index is constructed, you can instead use the class method constructors available in the

pd.MultiIndex:

pd.MultiIndex.from_arrays([['a', 'a', 'b', 'b'], [1, 2, 1, 2]])

pd.MultiIndex.from_tuples([('a', 1), ('a', 2), ('b', 1), ('b', 2)])

- For various reasons, partial slices and other similar operations require the levels in the

MultiIndexto be in sorted (i.e., lexographical) order. Pandas provides a number of convenience routines to perform this type of sorting; examples are thesort_index()andsortlevel()methods of the DataFrame:

data = data.sort_index()

-

Remember that columns are primary in a DataFrame, and the syntax used for multiply indexed Series applies to the columns.

-

Another way to rearrange hierarchical data is to turn the index labels into columns; this can be accomplished with the

reset_indexmethod.

pop_flat = pop.reset_index(name='population')

- We've previously seen that Pandas has built-in data aggregation methods, such as

mean(),sum(), andmax(). For hierarchically indexed data, these can be passed alevelparameter that controls which subset of the data the aggregate is computed on.

data_mean = health_data.mean(level='year') #average over the year

- By further making use of the axis keyword, we can take the mean among levels on the columns as well:

data_mean.mean(axis=1, level='type') # row average over the year

- panel data is fundamentally a dense data representation, while multi-indexing is fundamentally a sparse data representation. As the number of dimensions increases, the dense representation can become very inefficient for the majority of real-world datasets.

Combining Datasets: Concat and Append

TOC

- Recall: Concatenation of NumPy Arrays

- Simple Concatenation with

pd.concat- Duplicate indices

- Catching the repeats as an error

- Ignoring the index

- Adding MultiIndex keys

- Concatenation with joins

- The

append()method

- Duplicate indices

-

By default, the concatenation takes place row-wise within the DataFrame (i.e., axis=0/'row' or stack). Like

np.concatenate,pd.concatallows specification of an axis along which concatenation will take place. -

One important difference between

np.concatenateandpd.concatis that Pandas concatenation preserves indices, even if the result will have duplicate indices! While this is valid within DataFrames, the outcome is often undesirable. pd.concat() gives us a few ways to handle it. (i.e. next bullet point) -

If you'd like to simply verify that the indices in the result of

pd.concat()do not overlap, you can specify theverify_integrityflag. With this set toTrue, the concatenation will raise an exception if there are duplicate indices. -

Because direct array concatenation is so common, Series and DataFrame objects have an

appendmethod that can accomplish the same thing in fewer keystrokes:df1.append(df2)- Keep in mind that unlike the

append()andextend()methods of Python lists, theappend()method in Pandas does not modify the original object–instead it creates a new object with the combined data. Thus, if you plan to do multiple append operations, it is generally better to build a list of DataFrames and pass them all at once to theconcat()function.

- Keep in mind that unlike the

Combining Datasets: Merge and Join

TOC

- Relational Algebra

- The behavior implemented in

pd.merge()is a subset of what is known as relational algebra, which is a formal set of rules for manipulating relational data, and forms the conceptual foundation of operations available in most databases. - The strength of the relational algebra approach is that it proposes several primitive operations, which become the building blocks of more complicated operations on any dataset. With this lexicon of fundamental operations implemented efficiently in a database or other program, a wide range of fairly complicated composite operations can be performed.

- The behavior implemented in

- Categories of Joins

- The

pd.merge()function implements a number of types of joins: the one-to-one, many-to-one, and many-to-many joins. All three types of joins are accessed via an identical call to the pd.merge() interface; the type of join performed depends on the form of the input data. - One-to-one joins

- keep in mind that the merge in general discards the index, except in the special case of merges by index (see the

left_indexandright_indexkeywords)

- keep in mind that the merge in general discards the index, except in the special case of merges by index (see the

- Many-to-one joins

- Many-to-many joins

- The

- Specification of the Merge Key

- The

onkeyword - The

left_onandright_onkeywords- At times you may wish to merge two datasets with different column names; for example, we may have a dataset in which the employee name is labeled as "name" rather than "employee". In this case, we can use the

left_onandright_onkeywords to specify the two column names

pd.merge(df1, df3, left_on="employee", right_on="name").drop('name', axis=1) - At times you may wish to merge two datasets with different column names; for example, we may have a dataset in which the employee name is labeled as "name" rather than "employee". In this case, we can use the

- The

left_indexandright_indexkeywords- For convenience, DataFrames implement the

join()method, which performs a merge that defaults to joining on indices

df1a.join(df2a)- If you'd like to mix indices and columns, you can combine

left_indexwithright_onorleft_onwithright_indexto get the desired behavior

pd.merge(df1a, df3, left_index=True, right_on='name') - For convenience, DataFrames implement the

- The

- Specifying Set Arithmetic for Joins

- We can specify this explicitly using the how keyword, which defaults to "inner"

- Other options for the how keyword are 'outer', 'left', and 'right'

- Overlapping Column Names: The

suffixesKeyword- In a case where your two input DataFrames have conflicting column names, it is possible to specify a custom suffix using the suffixes keyword

pd.merge(df8, df9, on="name", suffixes=["_L", "_R"])

Aggregation and Grouping

TOC

-

Planets Data

-

Simple Aggregation in Pandas

- For a

DataFrame, by default the aggregates (i.e. compute the summary statistics) return results within each column - There is a convenience method

describe()that computes several common aggregates for each column and returns the result.

- For a

-

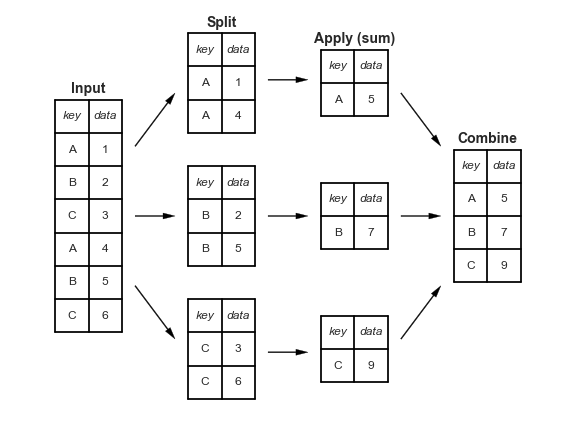

GroupBy: Split, Apply, Combine

-

This makes clear what the groupby accomplishes:

- The *split* step involves breaking up and grouping a DataFrame depending on the value of the specified key. - The *apply* step involves computing some function, usually an aggregate, transformation, or filtering, within the individual groups. - The *combine* step merges the results of these operations into an output array.- While this could certainly be done manually using some combination of the masking, aggregation, and merging commands covered earlier, an important realization is that the intermediate splits do not need to be explicitly instantiated. Rather, the GroupBy can (often) do this in a single pass over the data, updating the sum, mean, count, min, or other aggregate for each group along the way. The power of the GroupBy is that it abstracts away these steps: the user need not think about how the computation is done under the hood, but rather thinks about the operation as a whole.

- The name "group by" comes from a command in the SQL database language, but it is perhaps more illuminative to think of it in the terms first coined by Hadley Wickham of Rstats fame: split, apply, combine.

- Notice that what is returned is not a set of

DataFrames, but aDataFrameGroupByobject. This object is where the magic is: you can think of it as a special view of the DataFrame, which is poised to dig into the groups but does no actual computation until the aggregation is applied. This "lazy evaluation" approach means that common aggregates can be implemented very efficiently in a way that is almost transparent to the user. - Split, apply, combine

- The GroupBy object

- Column indexing

- Iteration over groups

- Dispatch methods

- Aggregate, filter, transform, apply

- Aggregation

- Filtering

- Transformation

- The

apply()method- The

apply()method lets you apply an arbitrary function to the group results. The function should take aDataFrame, and return either a Pandas object (e.g.,DataFrame,Series) or a scalar; the combine operation will be tailored to the type of output returned.

df.groupby('key').apply(norm_by_data2) - The

- Specifying the split key

- A list, array, series, or index providing the grouping keys

- A dictionary or series mapping index to group

- Any Python function

- A list of valid keys

-

Grouping example

Pivotal tables

TOC

-

Motivating Pivot Tables

- The pivot table takes simple column-wise data as input, and groups the entries into a two-dimensional table that provides a multidimensional summarization of the data. The difference between pivot tables and GroupBy can sometimes cause confusion; It helpsto think of pivot tables as essentially a multidimensional version of GroupBy aggregation. That is, you split-apply-combine, but both the split and the combine happen across not a one-dimensional index, but across a two-dimensional grid.

-

Pivot Tables by Hand

titanic.groupby(['sex', 'class'])['survived'].aggregate('mean').unstack() -

Pivot Table Syntax

titanic.pivot_table('survived', index='sex', columns='class')- Multi-level pivot tables

age = pd.cut(titanic['age'], [0, 18, 80]) titanic.pivot_table('survived', ['sex', age], 'class') - Additional pivot table options

- Multi-level pivot tables

-

Example: Birthrate DataFurther data exploration¶

- Further data exploration

- You can learn more about sigma-clipping operations in a book I coauthored with Željko Ivezić, Andrew J. Connolly, and Alexander Gray: "Statistics, Data Mining, and Machine Learning in Astronomy" (Princeton University Press, 2014)

- Further data exploration

Vectorized String Operations

TOC

-

Introducing Pandas String Operations

- This vectorization of operations simplifies the syntax of operating on arrays of data: we no longer have to worry about the size or shape of the array, but just about what operation we want done. For arrays of strings, NumPy does not provide such simple access, and thus you're stuck using a more verbose loop syntax

-

Tables of Pandas String Methods

-

Methods similar to Python string methods

- Nearly all Python's built-in string methods are mirrored by a Pandas vectorized string method. Here is a list of Pandas

strmethods that mirror Python string methodslen()lower()translate()islower()

ljust()upper()startswith()isupper()

rjust()find()endswith()isnumeric()

center()rfind()isalnum()isdecimal()

zfill()index()isalpha()split()

strip()rindex()isdigit()rsplit()

rstrip()capitalize()isspace()partition()

lstrip()swapcase()istitle()rpartition()

- Nearly all Python's built-in string methods are mirrored by a Pandas vectorized string method. Here is a list of Pandas

-

Methods using regular expressions

Method Description match()Call re.match()on each element, returning a boolean.extract()Call re.match()on each element, returning matched groups as strings.findall()Call re.findall()on each elementreplace()Replace occurrences of pattern with some other string contains()Call re.search()on each element, returning a booleancount()Count occurrences of pattern split()Equivalent to str.split(), but accepts regexps rsplit()Equivalent to str.rsplit(), but accepts regexps -

Miscellaneous methods

Method Description get()Index each element slice()Slice each element slice_replace()Replace slice in each element with passed value cat()Concatenate strings repeat()Repeat values normalize()Return Unicode form of string pad()Add whitespace to left, right, or both sides of strings wrap()Split long strings into lines with length less than a given width join()Join strings in each element of the Series with passed separator get_dummies()extract dummy variables as a dataframe - Vectorized item access and slicing

- Indicator variables

-

-

Example: Recipe Database

- A simple recipe recommender

- Going further with recipes

Working with Time Series

TOC

-

Date and time data comes in a few flavors, which we will discuss here:

- Time stamps reference particular moments in time (e.g., July 4th, 2015 at 7:00am).

- Time intervals and periods reference a length of time between a particular beginning and end point; for example, the year 2015. Periods usually reference a special case of time intervals in which each interval is of uniform length and does not overlap (e.g., 24 hour-long periods comprising days).

- Time deltas or durations reference an exact length of time (e.g., a duration of 22.56 seconds).

-

Dates and Times in Python

-

Native Python dates and times:

datetimeanddateutil- Python's basic objects for working with dates and times reside in the built-in

datetimemodule. Along with the third-partydateutilmodule, you can use it to quickly perform a host of useful functionalities on dates and times. - A related package to be aware of is

pytz, which contains tools for working with the most migrane-inducing piece of time series data: time zones.

- Python's basic objects for working with dates and times reside in the built-in

-

Typed arrays of times: NumPy's

datetime64- The weaknesses of Python's datetime format inspired the NumPy team to add a set of native time series data type to NumPy. The

datetime64dtype encodes dates as 64-bit integers, and thus allows arrays of dates to be represented very compactly. Thedatetime64requires a very specific input format:

import numpy as np date = np.array('2015-07-04', dtype=np.datetime64) date >>> array(datetime.date(2015, 7, 4), dtype='datetime64[D]')-

One detail of the

datetime64andtimedelta64objects is that they are built on a fundamental time unit. Because thedatetime64object is limited to 64-bit precision, the range of encodable times is $2^{64}$ times this fundamental unit. In other words,datetime64imposes a trade-off between time resolution and maximum time span. -

The time zone is automatically set to the local time on the computer executing the code. You can force any desired fundamental unit using one of many format codes

Code Meaning Time span (relative) Time span (absolute) Y Year ± 9.2e18 years [9.2e18 BC, 9.2e18 AD] M Month ± 7.6e17 years [7.6e17 BC, 7.6e17 AD] W Week ± 1.7e17 years [1.7e17 BC, 1.7e17 AD] D Day ± 2.5e16 years [2.5e16 BC, 2.5e16 AD] h Hour ± 1.0e15 years [1.0e15 BC, 1.0e15 AD] m Minute ± 1.7e13 years [1.7e13 BC, 1.7e13 AD] s Second ± 2.9e12 years [ 2.9e9 BC, 2.9e9 AD] ms Millisecond ± 2.9e9 years [ 2.9e6 BC, 2.9e6 AD] us Microsecond ± 2.9e6 years [290301 BC, 294241 AD] ns Nanosecond ± 292 years [ 1678 AD, 2262 AD] ps Picosecond ± 106 days [ 1969 AD, 1970 AD] fs Femtosecond ± 2.6 hours [ 1969 AD, 1970 AD] as Attosecond ± 9.2 seconds [ 1969 AD, 1970 AD] - For the types of data we see in the real world, a useful default is

datetime64[ns], as it can encode a useful range of modern dates with a suitably fine precision. - we will note that while the

datetime64data type addresses some of the deficiencies of the built-in Python datetime type, it lacks many of the convenient methods and functions provided bydatetimeand especiallydateutil.

- The weaknesses of Python's datetime format inspired the NumPy team to add a set of native time series data type to NumPy. The

-

Dates and times in pandas: best of both worlds

- Pandas builds upon all the tools just discussed to provide a

Timestampobject, which combines the ease-of-use ofdatetimeanddateutilwith the efficient storage and vectorized interface ofnumpy.datetime64. From a group of theseTimestampobjects, Pandas can construct aDatetimeIndexthat can be used to index data in aSeriesorDataFrame

- Pandas builds upon all the tools just discussed to provide a

-

The power of datetime and dateutil lie in their flexibility and easy syntax: you can use these objects and their built-in methods to easily perform nearly any operation you might be interested in. Where they break down is when you wish to work with large arrays of dates and times: just as lists of Python numerical variables are suboptimal compared to NumPy-style typed numerical arrays, lists of Python datetime objects are suboptimal compared to typed arrays of encoded dates.

-

-

Pandas Time Series: Indexing by Time

- Where the Pandas time series tools really become useful is when you begin to index data by timestamps.

-

Pandas Time Series Data Structures

- For time stamps, Pandas provides the

Timestamptype. The associated Index structure isDatetimeIndex. - For time Periods, Pandas provides the

Periodtype. This encodes a fixed-frequency interval based onnumpy.datetime64. The associated index structure isPeriodIndex. - For time deltas or durations, Pandas provides the

Timedeltatype.Timedeltais a more efficient replacement for Python's nativedatetime.timedeltatype, and is based onnumpy.timedelta64. The associated index structure isTimedeltaIndex. - The most fundamental of these date/time objects are the

TimestampandDatetimeIndexobjects. While these class objects can be invoked directly, it is more common to use thepd.to_datetime()function, which can parse a wide variety of formats. Passing a single date topd.to_datetime()yields aTimestamp; passing a series of dates by default yields aDatetimeIndexdates = pd.to_datetime([datetime(2015, 7, 3), '4th of July, 2015', '2015-Jul-6', '07-07-2015', '20150708']) dates >>> DatetimeIndex(['2015-07-03', '2015-07-04', '2015-07-06', '2015-07-07', '2015-07-08'], dtype='datetime64[ns]', freq=None) - A TimedeltaIndex is created, for example, when a date is subtracted from another:

dates - dates[0] >>> TimedeltaIndex(['0 days', '1 days', '3 days', '4 days', '5 days'], dtype='timedelta64[ns]', freq=None)- Regular sequences:

pd.date_range()

- For time stamps, Pandas provides the

-

Frequencies and Offsets

- Fundamental to these Pandas time series tools is the concept of a frequency or date offset.

Code Description Code Description D Calendar day B Business day W Weekly M Month end BM Business month end Q Quarter end BQ Business quarter end A Year end BA Business year end H Hours BH Business hours T Minutes S Seconds L Milliseonds U Microseconds N nanoseconds - The monthly, quarterly, and annual frequencies are all marked at the end of the specified period. By adding an S suffix to any of these, they instead will be marked at the beginning:

Code Description Code Description MS Month start BMS Business month start QS Quarter start BQS Business quarter start AS Year start BAS Business year start -

Resampling, Shifting, and Windowing

- Resampling and converting frequencies

- One common need for time series data is resampling at a higher or lower frequency. This can be done using the

resample()method, or the much simplerasfreq()method. The primary difference between the two is thatresample()is fundamentally a data aggregation, whileasfreq()is fundamentally a data selection.

- One common need for time series data is resampling at a higher or lower frequency. This can be done using the

- Time-shifts

- Rolling windows

- Resampling and converting frequencies

-

Where to Learn More

-

Example: Visualizing Seattle Bicycle Counts

- Visualizing the data

- Digging into the data

High-Performance Pandas: eval() and query()

TOC

-

As of version 0.13 (released January 2014), Pandas includes some experimental tools that allow you to directly access C-speed operations without costly allocation of intermediate arrays. These are the

eval()andquery()functions, which rely on theNumexprpackage. -

Motivating

query()andeval(): Compound Expressions- In other words, every intermediate step is explicitly allocated in memory. If the

xandyarrays are very large, this can lead to significant memory and computational overhead. TheNumexprlibrary gives you the ability to compute this type of compound expression element by element, without the need to allocate full intermediate arrays. - The benefit here is that

Numexprevaluates the expression in a way that does not use full-sized temporary arrays, and thus can be much more efficient than NumPy, especially for large arrays. The Pandaseval()andquery()tools that we will discuss here are conceptually similar, and depend on the Numexpr package.

- In other words, every intermediate step is explicitly allocated in memory. If the

-

pandas.eval()for Efficient Operations-

The

eval()function in Pandas uses string expressions to efficiently compute operations using DataFramespd.eval('df1 + df2 + df3 + df4') -

Operations supported by

pd.eval()- Comparison operators

- Bitwise operators

- Object attributes and indices

- Other operations

-

-

DataFrame.eval() for Column-Wise Operations

- Just as Pandas has a top-level

pd.eval()function, DataFrames have aneval()method that works in similar ways. The benefit of theeval()method is that columns can be referred to by name:

pd.eval("(df.A + df.B) / (df.C - 1)")-

Assignment in

DataFrame.eval()- In addition to the options just discussed,

DataFrame.eval()also allows assignment to any column.df.eval('D = (A - B) / C', inplace=True) # compute D based on A, B, and C

- In addition to the options just discussed,

-

Local variables in

DataFrame.eval()- The

DataFrame.eval()method supports an additional syntax that lets it work with local Python variables. - The

@character here marks a variable name rather than a column name, and lets you efficiently evaluate expressions involving the two "namespaces": the namespace of columns, and the namespace of Python objects. Notice that this@character is only supported by theDataFrame.eval()method, not by thepandas.eval()function, because thepandas.eval()function only has access to the one (Python) namespace.

- The

- Just as Pandas has a top-level

-

DataFrame.query()Method- Note that the

query()method also accepts the@flag to mark local variablesCmean = df['C'].mean() result1 = df[(df.A < Cmean) & (df.B < Cmean)] result2 = df.query('A < @Cmean and B < @Cmean') np.allclose(result1, result2)

- Note that the

-

Performance: When to Use These Functions

- When considering whether to use these functions, there are two considerations: computation time and memory use. Memory use is the most predictable aspect. As already mentioned, every compound expression involving NumPy arrays or Pandas DataFrames will result in implicit creation of temporary arrays

- If the size of the temporary DataFrames is significant compared to your available system memory (typically several gigabytes) then it's a good idea to use an eval() or query() expression.

- On the performance side,

eval()can be faster even when you are not maxing-out your system memory. The issue is how your temporary DataFrames compare to the size of the L1 or L2 CPU cache on your system (typically a few megabytes in 2016); if they are much bigger, theneval()can avoid some potentially slow movement of values between the different memory caches. In practice, I find that the difference in computation time between the traditional methods and the eval/query method is usually not significant–if anything, the traditional method is faster for smaller arrays! The benefit of eval/query is mainly in the saved memory, and the sometimes cleaner syntax they offer.

Further Resources

- Python Data Analysis Library — pandas: Python Data Analysis Library

- Python for Data Analysis - O'Reilly Media

- Newest 'pandas' Questions - Stack Overflow

- PyVideo.org

3. Machine Learning 💻

What Is Machine Learning?

-

The study of machine learning certainly arose from research in this context, but in the data science application of machine learning methods, it's more helpful to think of machine learning as a means of building models of data.

-

Fundamentally, machine learning involves building mathematical models to help understand data. "Learning" enters the fray when we give these models tunable parameters that can be adapted to observed data; in this way the program can be considered to be "learning" from the data. Once these models have been fit to previously seen data, they can be used to predict and understand aspects of newly observed data.

-

Categories of Machine Learning

- Supervised learning involves somehow modeling the relationship between measured features of data and some label associated with the data; once this model is determined, it can be used to apply labels to new, unknown data.

- Classification

- Regression

- Unsupervised learning involves modeling the features of a dataset without reference to any label, and is often described as "letting the dataset speak for itself."

- Clustering

- Dimensionality reduction

- In addition, there are so-called semi-supervised learning methods, which falls somewhere between supervised learning and unsupervised learning. Semi-supervised learning methods are often useful when only incomplete labels are available.

- Supervised learning involves somehow modeling the relationship between measured features of data and some label associated with the data; once this model is determined, it can be used to apply labels to new, unknown data.

-

Qualitative Examples of Machine Learning Applications

- Classification: Predicting discrete labels

- Regression: Predicting continuous labels

- Clustering: Inferring labels on unlabeled data

- Dimensionality reduction: Inferring structure of unlabeled data

-

Summary

Introducing Scikit-Learn

TOC

- Data Representation in Scikit-Learn

- The best way to think about data within Scikit-Learn is in terms of tables of data.

- Data as table

- Features matrix

- Target array

- Often one point of confusion is how the target array differs from the other features columns. The distinguishing feature of the target array is that it is usually the quantity we want to predict from the data: in statistical terms, it is the dependent variable.

- Scikit-Learn's Estimator API

-

The Scikit-Learn API is designed with the following guiding principles in mind, as outlined in the Scikit-Learn API paper:

- Consistency: All objects share a common interface drawn from a limited set of methods, with consistent documentation.

- Inspection: All specified parameter values are exposed as public attributes.

- Limited object hierarchy: Only algorithms are represented by Python classes; datasets are represented in standard formats (NumPy arrays, Pandas

DataFrames, SciPy sparse matrices) and parameter names use standard Python strings. - Composition: Many machine learning tasks can be expressed as sequences of more fundamental algorithms, and Scikit-Learn makes use of this wherever possible.

- Sensible defaults: When models require user-specified parameters, the library defines an appropriate default value.

-

In practice, these principles make Scikit-Learn very easy to use, once the basic principles are understood. Every machine learning algorithm in Scikit-Learn is implemented via the Estimator API, which provides a consistent interface for a wide range of machine learning applications.

-

Basics of the API

- Most commonly, the steps in using the Scikit-Learn estimator API are as follows (we will step through a handful of detailed examples in the sections that follow).

- Choose a class of model by importing the appropriate estimator class from Scikit-Learn.

- Choose model hyperparameters by instantiating this class with desired values.

- Arrange data into a features matrix and target vector following the discussion above.

- Fit the model to your data by calling the

fit()method of the model instance. - Apply the Model to new data:

- For supervised learning, often we predict labels for unknown data using the

predict()method. - For unsupervised learning, we often transform or infer properties of the data using the

transform()orpredict()method.

- For supervised learning, often we predict labels for unknown data using the

- Most commonly, the steps in using the Scikit-Learn estimator API are as follows (we will step through a handful of detailed examples in the sections that follow).

-

Supervised learning example: Simple linear regression

- Choose a class of model

- Choose model hyperparameters

- An important point is that a class of model is not the same as an instance of a model.

- In Scikit-Learn, by convention all model parameters that were learned during the

fit()process have trailing underscores - Keep in mind that when the model is instantiated, the only action is the storing of these hyperparameter values. In particular, we have not yet applied the model to any data: the Scikit-Learn API makes very clear the distinction between choice of model and application of model to data.

- Arrange data into a features matrix and target vector

- In general, Scikit-Learn does not provide tools to draw conclusions from internal model parameters themselves: interpreting model parameters is much more a statistical modeling question than a machine learning question.

- Fit the model to your data

- Predict labels for unknown data

-

Supervised learning example: Iris classification

- Because it is so fast and has no hyperparameters to choose, Gaussian naive Bayes is often a good model to use as a baseline classification, before exploring whether improvements can be found through more sophisticated models.

-

Unsupervised learning example: Iris dimensionality

- Often dimensionality reduction is used as an aid to visualizing data: after all, it is much easier to plot data in two dimensions than in four dimensions or higher!

-

Unsupervised learning: Iris clustering

-

- Application: Exploring Hand-written Digits

- Loading and visualizing the digits data

- Unsupervised learning: Dimensionality reduction

- Classification on digits

- Summary

Hyperparameters and Model Validation

TOC

- Thinking about Model Validation

- Model validation the wrong way

- Model validation the right way: Holdout sets

- Model validation via cross-validation

- One disadvantage of using a holdout set for model validation is that we have lost a portion of our data to the model training.

- One way to address this is to use cross-validation; that is, to do a sequence of fits where each subset of the data is used both as a training set and as a validation set.

- Scikit-Learn implements a number of useful cross-validation schemes that are useful in particular situations; these are implemented via iterators in the

cross_validationmodule.

- Selecting the Best Model

-

Of core importance is the following question: if our estimator is underperforming, how should we move forward? There are several possible answers:

- Use a more complicated/more flexible model

- Use a less complicated/less flexible model

- Gather more training samples

- Gather more data to add features to each sample

-

The answer to this question is often counter-intuitive. In particular, sometimes using a more complicated model will give worse results, and adding more training samples may not improve your results! The ability to determine what steps will improve your model is what separates the successful machine learning practitioners from the unsuccessful.

-

The Bias-variance trade-off

- For high-bias models, the performance of the model on the validation set is similar to the performance on the training set.

- For high-variance models, the performance of the model on the validation set is far worse than the performance on the training set.

-

Validation curves in Scikit-Learn

-

- Learning Curves

-

We see that the behavior of the validation curve has not one but two important inputs: the model complexity and the number of training points. It is often useful to to explore the behavior of the model as a function of the number of training points, which we can do by using increasingly larger subsets of the data to fit our model. A plot of the training/validation score with respect to the size of the training set is known as a learning curve.

-

One important aspect of model complexity is that the optimal model will generally depend on the size of your training data.

-

The notable feature of the learning curve is the convergence to a particular score as the number of training samples grows. In particular, once you have enough points that a particular model has converged, adding more training data will not help you! The only way to increase model performance in this case is to use another (often more complex) model.

-

The general behavior we would expect from a learning curve is this:

- A model of a given complexity will overfit a small dataset: this means the training score will be relatively high, while the validation score will be relatively low.

- A model of a given complexity will underfit a large dataset: this means that the training score will decrease, but the validation score will increase.

- A model will never, except by chance, give a better score to the validation set than the training set: this means the curves should keep getting closer together but never cross.

-

Learning curves in Scikit-Learn

- This (learning curve) is a valuable diagnostic, because it gives us a visual depiction of how our model responds to increasing training data. In particular, when your learning curve has already converged (i.e., when the training and validation curves are already close to each other) adding more training data will not significantly improve the fit!

-

- Validation in Practice: Grid Search

- The grid search provides many more options, including the ability to specify a custom scoring function, to parallelize the computations, to do randomized searches, and more.

- Summary

Feature Engineering

TOC

-

Categorical Features

- There is one clear disadvantage of this approach (one-hot encoding): if your category has many possible values, this can greatly increase the size of your dataset. However, because the encoded data contains mostly zeros, a sparse output can be a very efficient solution

sklearn.preprocessing.OneHotEncoderandsklearn.feature_extraction.FeatureHasherare two additional tools that Scikit-Learn includes to support this type of encoding.

-

Text Features

- There are some issues with this approach (using Scikit-Learn's

CountVectorizer), however: the raw word counts lead to features which put too much weight on words that appear very frequently, and this can be sub-optimal in some classification algorithms. One approach to fix this is known as term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF–IDF) which weights the word counts by a measure of how often they appear in the documentsfrom sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer vec = TfidfVectorizer() X = vec.fit_transform(sample) pd.DataFrame(X.toarray(), columns=vec.get_feature_names())

- There are some issues with this approach (using Scikit-Learn's

-

Image Features

- A comprehensive summary of feature extraction techniques for images is well beyond the scope of this section, but you can find excellent implementations of many of the standard approaches in the Scikit-Image project.

-

Derived Features

- This idea of improving a model not by changing the model, but by transforming the inputs, is fundamental to many of the more powerful machine learning methods.

-

Imputation of Missing Data

-

Feature Pipelines

- This pipeline looks and acts like a standard Scikit-Learn object, and will apply all the specified steps to any input data.

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline model = make_pipeline(Imputer(strategy='mean'), PolynomialFeatures(degree=2), LinearRegression())

- This pipeline looks and acts like a standard Scikit-Learn object, and will apply all the specified steps to any input data.

In Depth: Naive Bayes Classification

TOC

- Naive Bayes models are a group of extremely fast and simple classification algorithms that are often suitable for very high-dimensional datasets. Because they are so fast and have so few tunable parameters, they end up being very useful as a quick-and-dirty baseline for a classification problem.

- Bayesian Classification

- This is where the "naive" in "naive Bayes" comes in: if we make very naive assumptions about the generative model for each label, we can find a rough approximation of the generative model for each class, and then proceed with the Bayesian classification.

- Different types of naive Bayes classifiers rest on different naive assumptions about the data

- Gaussian Naive Bayes

- Perhaps the easiest naive Bayes classifier to understand is Gaussian naive Bayes. In this classifier, the assumption is that data from each label is drawn from a simple Gaussian distribution.

- A nice piece of this Bayesian formalism is that it naturally allows for probabilistic classification, which we can compute using the

predict_probamethod - in general, the boundary in Gaussian naive Bayes is quadratic

- Multinomial Naive Bayes

- The multinomial distribution describes the probability of observing counts among a number of categories, and thus multinomial naive Bayes is most appropriate for features that represent counts or count rates.

- Example: Classifying Text

- When to Use Naive Bayes

- Because naive Bayesian classifiers make such stringent assumptions about data, they will generally not perform as well as a more complicated model. That said, they have several advantages:

- They are extremely fast for both training and prediction

- They provide straightforward probabilistic prediction

- They are often very easily interpretable

- They have very few (if any) tunable parameters

- Naive Bayes classifiers tend to perform especially well in one of the following situations:

- When the naive assumptions actually match the data (very rare in practice)

- For very well-separated categories, when model complexity is less important

- For very high-dimensional data, when model complexity is less important

- Because naive Bayesian classifiers make such stringent assumptions about data, they will generally not perform as well as a more complicated model. That said, they have several advantages:

In Depth: Linear Regression

TOC

- Simple Linear Regression

- Basis Function Regression

- Notice that this is still a linear model—the linearity refers to the fact that the coefficients $a_n$ never multiply or divide each other.

- Polynomial basis functions

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures x = np.array([2, 3, 4]) poly = PolynomialFeatures(3, include_bias=False) poly.fit_transform(x[:, None]) - Gaussian basis functions

- one useful pattern is to fit a model that is not a sum of polynomial bases, but a sum of Gaussian bases. (add pic here)

- This is typical over-fitting behavior when basis functions overlap: the coefficients of adjacent basis functions blow up and cancel each other out.

- Regularization

- Ridge regression ($L_2$ Regularization)

- Perhaps the most common form of regularization is known as ridge regression or $L_2$ regularization, sometimes also called Tikhonov regularization. This proceeds by penalizing the sum of squares (2-norms) of the model coefficients; in this case, the penalty on the model fit would be

$$P = \alpha\sum_{n=1}^N \theta_n^2$$

where $\alpha$ is a free parameter that controls the strength of the penalty.

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge model = make_pipeline(GaussianFeatures(30), Ridge(alpha=0.1)) basis_plot(model, title='Ridge Regression')

- Perhaps the most common form of regularization is known as ridge regression or $L_2$ regularization, sometimes also called Tikhonov regularization. This proceeds by penalizing the sum of squares (2-norms) of the model coefficients; in this case, the penalty on the model fit would be

$$P = \alpha\sum_{n=1}^N \theta_n^2$$

where $\alpha$ is a free parameter that controls the strength of the penalty.

- Lasso regression ($L_1$ regularization)

-

Another very common type of regularization is known as lasso, and involves penalizing the sum of absolute values (1-norms) of regression coefficients: $$P = \alpha\sum_{n=1}^N|\theta_n|$$

-

due to geometric reasons lasso regression tends to favor sparse models where possible: that is, it preferentially sets model coefficients to exactly zero.

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso model = make_pipeline(GaussianFeatures(30), Lasso(alpha=0.001)) basis_plot(model, title='Lasso Regression') -

- Ridge regression ($L_2$ Regularization)

- Example: Predicting Bicycle Traffic

In-Depth: Support Vector Machines

TOC

- Motivating Support Vector Machines

- Generative classification: when learning a simple model describing the distribution of each underlying class, and uses these generative models to probabilistically determine labels for new points .

- In SVM we consider discriminative classification: rather than modeling each class, we simply find a line or curve (in two dimensions) or manifold (in multiple dimensions) that divides the classes from each other.

- Support Vector Machines: Maximizing the Margin

-

Support vector machines offer one way to improve on this. The intuition is this: rather than simply drawing a zero-width line between the classes, we can draw around each line a margin of some width, up to the nearest point.

-

In support vector machines, the line that maximizes this margin is the one we will choose as the optimal model. Support vector machines are an example of such a maximum margin estimator.

-

Fitting a support vector machine

from sklearn.svm import SVC # "Support vector classifier" model = SVC(kernel='linear', C=1E10) model.fit(X, y)- A key to this classifier's success is that for the fit, only the position of the support vectors matter; any points further from the margin which are on the correct side do not modify the fit! Technically, this is because these points do not contribute to the loss function used to fit the model, so their position and number do not matter so long as they do not cross the margin.

-

Beyond linear boundaries: Kernel SVM

- Idea: when linear separation is not possible, project the data into a higher dimension such that a linear separator would be sufficient.

- One strategy to this end is to compute a basis function centered at every point in the dataset, and let the SVM algorithm sift through the results. This type of basis function transformation is known as a kernel transformation, as it is based on a similarity relationship (or kernel) between each pair of points.

- A potential problem with this strategy—projecting $N$ points into $N$ dimensions—is that it might become very computationally intensive as $N$ grows large. However, because of a neat little procedure known as the kernel trick, a fit on kernel-transformed data can be done implicitly—that is, without ever building the full $N$-dimensional representation of the kernel projection! This kernel trick is built into the SVM, and is one of the reasons the method is so powerful.

- In Scikit-Learn, we can apply kernelized SVM simply by changing our linear kernel to an RBF (radial basis function) kernel, using the kernel model hyperparameter:

clf = SVC(kernel='rbf', C=1E6) clf.fit(X, y) -

Tuning the SVM: Softening Margins

- the SVM implementation has a bit of a fudge-factor which "softens" the margin: that is, it allows some of the points to creep into the margin if that allows a better fit.

- The hardness of the margin is controlled by a tuning parameter, most often known as $C$. For very large $C$, the margin is hard, and points cannot lie in it. For smaller $C$, the margin is softer, and can grow to encompass some points.

-

- Example: Face Recognition

- Support Vector Machine Summary

- Pros:

- Their dependence on relatively few support vectors means that they are very compact models, and take up very little memory.

- Once the model is trained, the prediction phase is very fast.

- Because they are affected only by points near the margin, they work well with high-dimensional data—even data with more dimensions than samples, which is a challenging regime for other algorithms.

- Their integration with kernel methods makes them very versatile, able to adapt to many types of data.

- Cons:

- The scaling with the number of samples $N$ is $\mathcal{O}[N^3]$ at worst, or $\mathcal{O}[N^2]$ for efficient implementations. For large numbers of training samples, this computational cost can be prohibitive.

- The results are strongly dependent on a suitable choice for the softening parameter $C$. This must be carefully chosen via cross-validation, which can be expensive as datasets grow in size.

- The results do not have a direct probabilistic interpretation. This can be estimated via an internal cross-validation (see the

probabilityparameter ofSVC), but this extra estimation is costly.

- Pros:

In-Depth: Decision Trees and Random Forests

TOC

- Random forests are an example of an ensemble method, meaning that it relies on aggregating the results of an ensemble of simpler estimators. The somewhat surprising result with such ensemble methods is that the sum can be greater than the parts: that is, a majority vote among a number of estimators can end up being better than any of the individual estimators doing the voting!

- Motivating Random Forests: Decision Trees

-

In machine learning implementations of decision trees, the questions generally take the form of axis-aligned splits in the data: that is, each node in the tree splits the data into two groups using a cutoff value within one of the features.

-

Creating a decision tree

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier tree = DecisionTreeClassifier().fit(X, y) -

Decision trees and over-fitting

- Over-fitting turns out to be a general property of decision trees: it is very easy to go too deep in the tree, and thus to fit details of the particular data rather than the overall properties of the distributions they are drawn from.

-

- Ensembles of Estimators: Random Forests

- Bagging makes use of an ensemble (a grab bag, perhaps) of parallel estimators, each of which over-fits the data, and averages the results to find a better classification. An ensemble of randomized decision trees is known as a random forest.