[book] Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models

A study note of [1]

Chapter 9 Causal inference using regression on the treatment variable

9.1 Causal inference and predictive comparisons

-

In the usual regression context, predictive inference relates to comparisons between units, whereas causal inference addresses comparisons of different treatments if applied to the same units.

-

More generally, causal inference can be viewed as a special case of prediction in which the goal is to predict what would have happened under different treatment options.

-

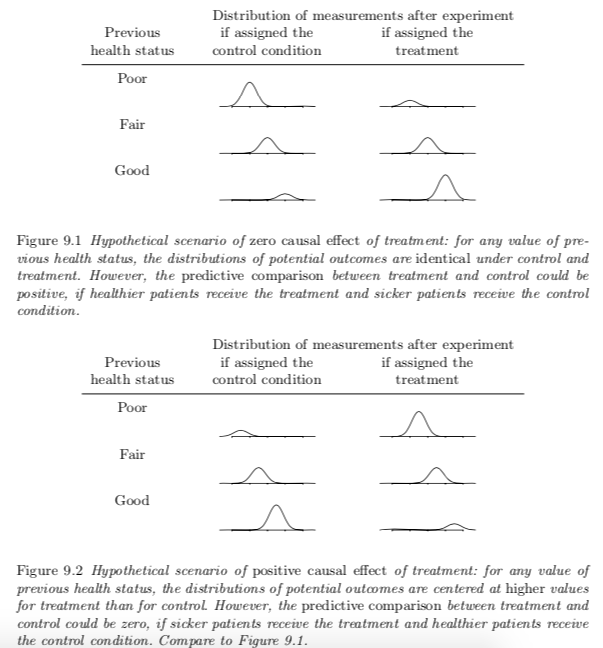

It's possible for a data to show zero causal effect but positive predictive comparison or vice versa

- The scenario illustrated in Figure 9.1 is called selection bias, because participatns are slecting themselves into different treatments

- To overcome this bias, we can either compare the averages across treatment groups within each group of the biased variable (previous health status here) OR, adjust for previous health status in the regression model

-

In general, causal effects can be estimated using regression if the model includes all confounding covariates (predictors that can affect treatment assignment or the outcome) and if the model is correct.

-

Omitting the confounder in regression model leads to biased estimate of causal effect:

-

True/correct model, where $x_i$ reprents the confounder

$$y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1T_i + \beta_2x_i + \epsilon_i$$ -

If the confounder is ignored

-

Then if we assume $x_i = \gamma_0 + \gamma_1T_i + v_i$, the second model is equivalent to replacing $x_i$ in the first model

\begin{align} y_i &= \beta_0 + \beta_1T_i + \beta_2( \gamma_0 + \gamma_1T_i)+ \epsilon_i\ & = \beta_0 +\beta_2\gamma_0 + (\beta_1 + \beta_2\gamma_1)T_i + \epsilon_i + \beta_2v_i \end{align}

-

That is $\beta_1^* = \beta_1 + \beta_2\gamma_1$. It's unbiased only when $\beta_2 = 0$ or $\gamma_1 = 0$, that is $x_i$ isn't a confoundering factor.

-

9.2 The fundamental problem of causal inference

- The causal effect of a treatment $T$ on an outcome $y$ for an observational or experimental unit $i$ can be defined by comparisons between the outcomes that would have occurred under each of the different treatment possibilities.

- Counterfactual: it represents what would have happend to the individual if assigned to control instead of treatment

- The so-called fundamental problem of causal inference is that at most one of these two potential outcomes, $y_i^0$ and $y_i^1$, can be observed for each unit $i$.

- How to get around the problem

- To make it clear, we can never measure a causal effect directly

- Instead we can think of causal inference as a prediction of what would happen to unit $i$ if $T_i = 0$ or $T_i = 1$. It's thus predictive inference in the potential-outcome framework.

- Estimating calsual effects requires one or more combination of the following

- Close substitutes for the potential outcomes

- Randomization

- Statistical adjustment

9.3 Randomized experiments

-

Random sampling and random treatment assignment allow us to estimate the average causal effect of the treatment in the population

$$\text{average treatment effect} = \text{avg}(y_i^1 - y_i^0)$$ -

Randomized experiment is the cleanest way to estimate the population average, in which each unit has a positive chance of receiving each of the possible treatments.

-

If randomized experiments are conducted within certain group of participants, the causal inference no longer generalize to the entire population.

-

When the causal inferences are merited for a specific sample or population, it's said to have internal validity; when those inferences can be generalized to a broader population of interest the study is said to have external validity

-

We avoid the term confounding covariates when describing adjustment in the context of a randomized experiment. Predictors are included in this context to increase precision. We expect them to be related to the outcome but not to the treatment assignment due to the randomiza- tion. Therefore they are not confounding covariates.

-

Modeling change from baseline (gain score) in response variable:

- In some cases the gain score can be more easily interpreted than the original outcome variable $y$.

- Using gain scores is most effective if the pre-treatment score is comparable to the post-treatment measure.

- Modeling the gain score without adjusting for baseline score (unnecessarily) assumes $\beta_2$ = 1 in model $y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1T_i + \beta_2x_i + \epsilon_i$; to aovid this assumption, we can adjust for baseline score, in which the estimate for treatment effect is equivalent to the estimated coefficient from the original model.

-

More than two treatment levels:

- With several discrete treatments that are unordered (such as in a comparison of three different sorts of psychotherapy), we can move to multilevel modeling, with the group index indicating the treatment assigned to each unit, and a second-level model on the group coefficients, or treatment effects.

-

No interference between units

- In above RCT analysis, we must assume also that the treatment assignment for one individual (unit) in the experiment does not affect the outcome for another. This has been incorporated into the “stable unit treat- ment value assumption” (SUTVA).

9.4 Treatment interactions and poststratification

- When including interaction between treatment and pre-treatment inputs, we get a range of estimates of treatment effects (as a function of pre-treatment input value). This range represents the variantion in estimated treatment effects as a function of pre-test score, not uncertainty in the estimated treatment effect.

- In general, for a linear regression model, the estimate obtained by including the interaction, and then averaging over the data, reduces to the estimate with no interaction.

- The motivation for including the interaction is thus to get a better idea of how the treatment effect varies with pre-treatment predictors, not simply to estimate an average effect.

- To estimate an average treatment effect, we can post-stratify—that is, average over the population. [2]

- Modeling interactions is important when we care about differences in the treatment effect for different groups, and post-stratification then arises naturally if a population average estimate is of interest.

9.5 Observational studies

-

In observational studies treatments are observed rather than assigned, study, there can be systematic differences between groups of units that receive different treatments—differences that are outside the control of the experimenter—and they can affect the outcome, $y$.

-

As opposed to making the same assumption as the completely randomized experiment, the key assumption underlying the estimate is that, conditional on the confounding covariates used in the analysis (here as inputs in the regression analysis), the distribution of units across treatment conditions is, in essence, “random” (in this case, pre-test score) with respect to the potential outcomes.

$$y^0, y^1 \perp T | X$$- This assumption is referred to as ignorability of the reatment assignment in the statistics literature and selection on observables in econometrics.

- we expect any two classes at the same levels of the confounding covariates (that is, pre-treatment variables; in our example, average pre-test score) to have had the same probability of receiving the supplemental version of the treatment.

- the ignorability assumption is that it requires that we control for all confounding covariates, the pre-treatment variables that are associated with both the treatment and the outcome.

-

Completely randomized experiments need not condition on any pre-treatment variables—this is why we can use a simple difference in means to estimate causal effects.

-

Randomized experiments that block or match satisfy ignorability conditional on the design variables used to block or match, and therefore these variables need to be included when estimating causal effects.

-

For ignorability to hold, it is not necessary that the two treatments be equally likely to be picked, but rather that the probability that a given treatment is picked should be equal, conditional on our confounding covariates. [3]

-

In general, one can never prove that the treatment assignment process in an observational study is ignorable—it is always possible that the choice of treatment depends on relevant information that has not been recorded.

-

Even ignorability is justified, model adjustment with confounding variables in regression analysis doesn't guarantee it's the best modeling approach for estimating treatment effect, as there are two primary concerns related to the distributions of the confounding covariates across the treatment groups: lack of complete overlap and lack of balance.

9.6 Understanding causal inference in observational studies

-

“infinite regress of causation”: looking for the most important cause of an outcome is a confusing framing for a research question because one can always find an earlier cause that affected the “cause” you determine to be the strongest from your data.

-

If you find yourself confused about what can be estimated and how the various aspects of your study should be defined, a simple strategy is to try to formalize the randomized experiment you would have liked to have done to answer your causal question. A perfect mapping rarely exists between this experimental ideal and your data so often you will be forced instead to figure out, given the data you have, what randomized experiment could be thought to have generated such data.

-

Finally, thinking about hypothetical randomized experiments can help with problems of trying to establish a causal link between two variables when neither has temporal priority and when they may have been simultaneously determined.

9.7 Do not control for post-treatment variables

- The problem of controlling post-treatment variables is that post-treatment variables is the intermediate result from treatment, when they are at the same level in the middle of study, it doesn't mean they are comparable at baseline (and highly likely they are not).

- Then controlling for post-treatment variables leads to imbalance in the baseline values of these varibales between treatment groups, which further leads to biased estimate of treatment effect

9.8 Intermediate outcomes and causal paths

-

A question addressed by simply running a regression of the outcome on the randomized treatment variable along with a predictor representing (post-treatment) “parenting” added to the equation; recall that this is often called a mediating variable or mediator.

- Implicitly, the coefficient on the treatment variable then creates a comparison between those randomly assigned to treatment and control, within subgroups defined by post-treatment variable

-

Regression controlling for intermediate outcomes cannot, in general, estimate “mediating” effects

-

The regression controlling for the intermediate outcome thus implicitly compares unlike groups of people and underestimates the treatment effect, because the treatment group in this comparison is made up of lower-performing children, on average.

-

randomization allows us to calculate causal effects of the variable randomized, but not other variables unless a whole new set of assumptions is made.

-

The key theoretical step here is to divide the population into categories based on their potential outcomes for the mediating variable—what would happen under each of the two treatment conditions. In statistical parlance, these categorizations are sometimes called principal strata.

- The problem is that the principal stratum labels are generally unobserved.

- It is theoretically possible to statistically infer principal-stratum categories based on covariates, especially if the treatment was randomized—because then at least we know that the distribution of principal strata is the same across the randomized groups.

- Principal strata are important because they can define, even if only theoretically, the categories of people for whom the treatment effect can be estimated from available data.

-

It should come as no surprise that it generally is also problematic for observational studies. The concern is nonignorability—systematic differences between groups defined conditional on the post-treatment intermediate outcome.

- Studying intermediate outcomes in an observational study involves two ignorability problems to deal with rather than just one, making it all the more challenging to obtain trustworthy results.

Chapter 10 Causal inference using more advanced models

10.1 Imbalance and lack of complete overlap

-

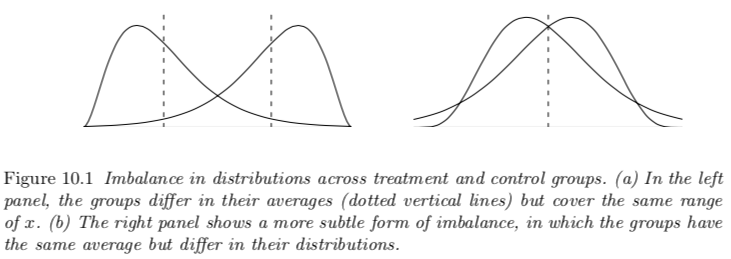

Imbalance: Imbalance occurs if the distributions of relevant pre-treatment variables differ for the treatment and control groups.

-

When treatment and control groups are unbalanced, the simple comparison of group averages, $\bar{y}_1−\bar{y}_0$, is not, in general, a good estimate of the average treatment effect. Instead, some analysis must be performed to adjust for pre-treatment differences between the groups.

-

Imbalance creates problems primarily because it forces us to rely more on the correctness of our model than we would have to if the samples were balanced.

-

In linear regression, assume a quadratic relationship between outcome $y$ and pre-treatment covariate $x$:

$$y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + \beta_2x_i^2 + \theta T_i + \epsilon_i$$-

Treatment effect $\theta$ can be derived as

$$\theta = \hat{y}_1 - \hat{y}_0 - \beta_1(\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_0) - \beta_2(\bar{x_1^2} - \bar{x_2^2})$$ -

$x$ are included since we can't assume they are exactly the same between treatment groups. And it can be seen that esitmate of $\theta$ depends on the difference in distrbution of $x$ between each arm. Unless, $x$'s are comparable (in distribution), the estimate will be biased for different level of quantities (depending on the true model parameterization).

-

-

To examine the imbalance between groups

- Compare difference in mean values divided by pooled within-group standard deviations for the groups under comparion

-

-

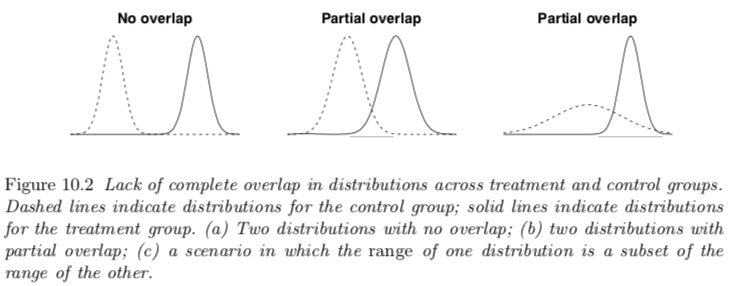

Lack of overlap: occurs if there are regions in the space of relevant pre-treatment variables where there are treated units but no controls, or controls but no treated units.

- There is complete overlap if this range is the same in the two groups.

- When treatment and control groups do not completely overlap, the data are inherently limited in what they can tell us about treatment effects in the regions of nonoverlap, i.e. there are treatment observations for which we have no counterfactuals and vice versa

- No amount of adjustment can create direct treatment/control comparisons, and one must either restrict inferences to the region of overlap, or rely on a model to extrapolate outside this region.

-

Imbalance is not the same as lack of overlap

- Imbalance does not necessarily imply lack of complete overlap

- Conversely, lack of complete overlap does not necessarily necessarily result in imbalance in the sense of different average values in the two groups.

-

Lack of complete overlap is a more serious problem than imbalance. But similar statistical methods are used in both scenarios

-

Broadly speaking, any differences across groups can be referred to as lack of balance across groups. The terms “imbalance” and “lack of balance” are commonly used as a shorthand for differences in averages, but more broadly they can refer to more general differences in distributions across groups.

10.2 Subclassification: effects and estimates for different subpopulations

-

Subclassification

- This analysis is similar to a regression with interaction between the treatment and the stratification variable

- To calculate the average treatment effect for treated, we would have to poststratify—that is, estimate the treatment effect separately for each category of statification factor, and then average these effects based on the distribution of the stratification factor in the population.

- This strategy has the advantage of imposing overlap and, moreover, forcing the control sample to have roughly the same covariate distribution as the treated sample.

- One drawback of subclassifying, however, is that when controlling for a continuous variable, some information may be lost when discretizing the variable. A more substantial drawback is that it is difficult to control for many variables at once.

-

Average treatment effects: whom do we average over?

- Depends on which part of the population we are interested in the effect of intervention acts, we will need to apply different weighting strategy:

- Effect of the treatment on the treated: weighting using the number of treatment participants

- Effect of the treatment on the controls: weighted by the number of control subjects in each subclass

- Deriving which effect depends on the original quesiton of interest and also if there are no/limited counterfactual the data for the other group, these data are likely inappropriate for drawing inferences from this group.

- We can think of the estimate of the effect of the treatment on the treated as a poststratified version of the estimate of the average causal effect.

- Depends on which part of the population we are interested in the effect of intervention acts, we will need to apply different weighting strategy:

10.3 Matching: subsetting the data to get overlapping and balanced treatment and control groups

-

Matching refers to a variety of procedures that restrict and reorganize the original sample in preparation for a statistical analysis.

-

Once the matched units have been selected out of the larger dataset, they can be analyzed by estimating a simple difference in average outcomes across treatment groups or by using regression methods to estimate the effect of the treatment in the area of overlap.

-

Matching and subclassification

- Matching on one variable is similar to subclassification except that it handles con- tinuous variables more precisely.

- Exact matching is difficult with many confounders, but “nearest- neighbor” matching is often still possible. This strategy matches treatment units to control units that are “similar” in terms of their confounders where the metric for similarity can be defined in any variety of ways, one of the most popular being the Mahalanobis distance, which is defined in matrix notation as $d(x^{(1)},x^{(2)}) = (x^{(1)} −x^{(2)})^t\Sigma^{−1}(x^{(1)} −x^{(2)})$, where $x^{(1)}$ and $x^{(2)}$ represent the vectors of predictors for points 1 and 2, and $\Sigma$ is the covariance of the predictors in the dataset.

-

Propensity score matching

- The propensity score for the $i$th individual is defined as the probability that he or she receives the treatment given everything we observe before the treatment (that is, all the confounding covariates for which we want to control).

- From its application mechanism (e.g. one-to-one matching or one-to-many matching), matching can be thought of as a way of discarding observations so that the remaining data show good balance and overlap.

- The goal of propensity score matching is not to ensure that each pair of matched observations is similar in terms of all their covariate values, but rather that the matched groups are similar on average across all their covariate values.

- The adequacy of the model used to estimate the propensity score can be evaluated by examining the balance that results on average across the matched groups.

- Insufficient overlap problem

- One option is to accept some lack of comparability (and corresponding level of imbalance in covariates).

- Another option is to eliminate the problematic treated observations.

- Matched pairs and correlation concern in analysis

- Although matching often results in pairs of treated and control units, we typically ignore the pairing in the analysis of the matched data.

- Propensity score matching works well (in appropriate settings) to create matched groups, but it does not necessarily created closely matched pairs.

- Because the pairing in the matching is performed in the analysis, not the data collection, it is not generally appropriate to add the complication of including the pairing in the model

- However, pairing in this way does affect variance calculations

- A quick way of assessing whether matching has achieved increased balance and overlap is to plot histograms of propensity scores across treated and control groups.

-

Different ways of using propensity score

-

Matching

- without replacement: any given control observation can only be used once as a match for the treatment observation (when have large data with enough controls)

- with replacement: one control is used multiple times to match with different treatment observation; a term which commonly refers to with one-to-one matching but could generalize to multiple control matches for each control. This approach create better balance and should yield estimates that are closer to the truth on average. Once such data are incorporated into a regression, however, the multiple matches reduce to single data points, which suggests that matching with replacement has limitations as a general strategy.

- Subclassification based on propensity score: The estimated treatment effects from each of the subclasses then can either be reported separately or combined in a weighted average with different weights used for different estimands.

- full matching: can be conceptualized as a fine stratification of the units where each statum has either (1) one treated unit and one control unit, (2) one treated unit and multiple control units, or (3) multiple treated units and one control unit.

-

Inverse of estimated propensity scores: to create a weight for each point in the data, with the goal that weighted averages of the data should look, in effect, like what would be obtained from a randomized experiment. (also called inverse probability of treatment weighting [IPTW])

- To obtain an estimate of an average treatment effect: $1/p_i$ weights for treated and $1/(1-p_i)$ for controls, where $p_i$ is the propensity score

- To obtain an estimate of the effect of the treatment on the treated: weight 1 for treated and $p_i/(1-p_i)$ for controls

- These strategies have the advantage (in terms of precision) of retaining the full sample.

- However, the weights may have wide variability and may be sensitive to model specification, which could lead to instability.

- Need to create stable weights and to use robust or nonparametric models to estimate the weights.

-

Used as the regression covariate: However, if observations that lie in areas where there is no overlap across treatment groups are not removed, the same problems regarding model extrapolation will persist.

-

Standard errors

- matching induces correlation among the matched observations.

- our uncertainty about the true propensity score is not reflected in our calculations.

- more complicated matching methods (for example, matching with replacement and many-to-one matching methods) generally require more sophisticated approaches to variance estimation. (exactly how?)

- Ultimately, one good solution may be a multilevel model that includes treatment interactions so that inferences explicitly recognize the decreased precision that can be obtained outside the region of overlap.

-

10.4 Lack of overlap when the assignment mechanism is known: regression discontinuity

-

If the treated and control groups are very different from each other, it can be more appropriate to identify the subset of the population with overlapping values of the predictor variables for both treatment and control conditions, and to estimate the causal effect (and the regression model) in this region only. Propensity score matching is one approach to lack of overlap.

-

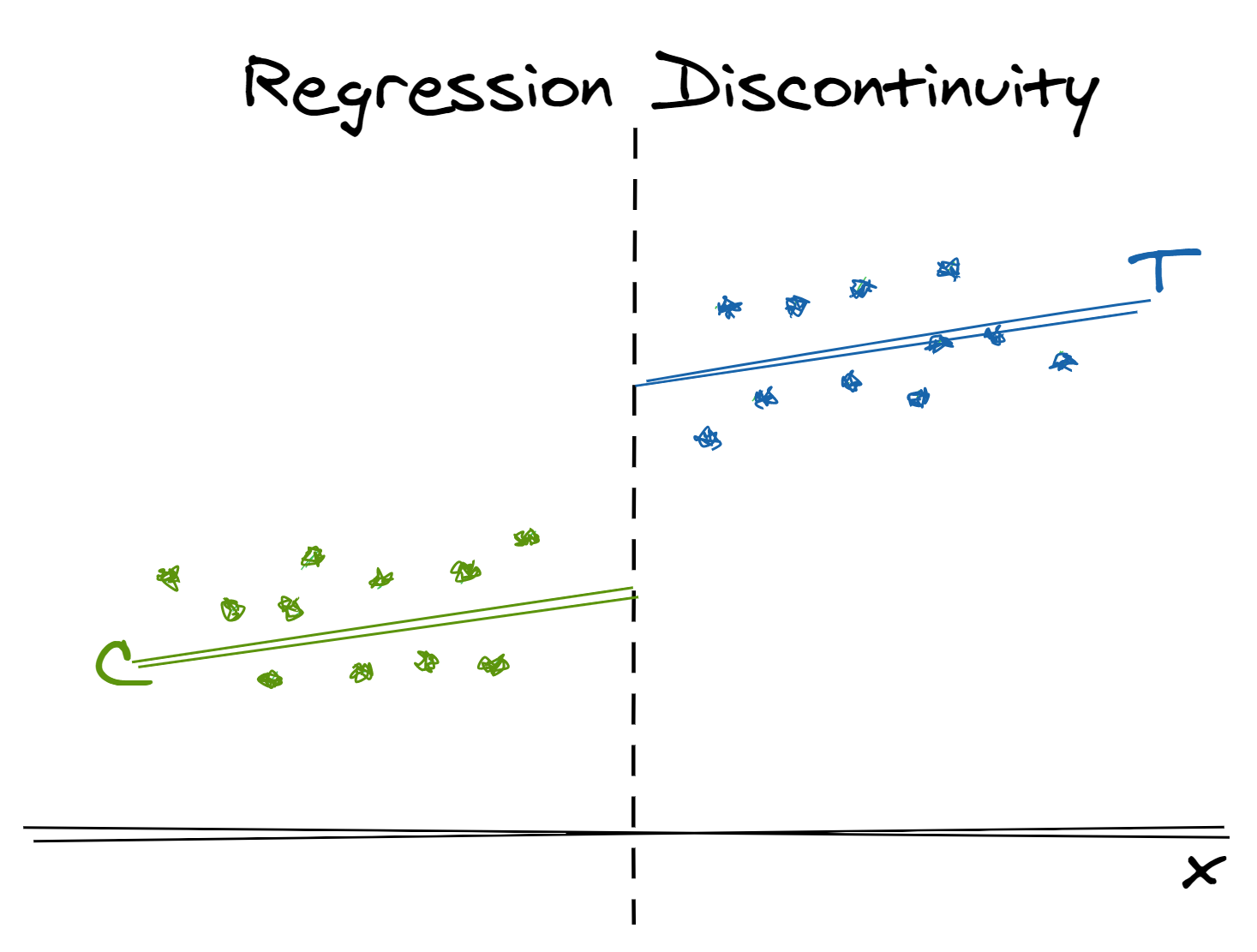

Sometimes a clean lack of overlap arises from a covariate that itself was used to assign units to treatment conditions. Regression discontinuity analysis is an approach for dealing with this extreme case of lack of overlap in which the assignment mechanism is clearly defined.

-

In a setting where one treatment occurs only for$ x < C$ and the other only for $x > C$, it is still possible to estimate the treatment effect for units with $x$ in the neighborhood of $C$, if we assume that the regression function—the average value of the outcome $y$, given $x$ and the treatment—is a continuous function of $x$ near the cutoff value $C$.

-

All we need to do is control for the input(s) used to determine treatment assignment—these are our confounding covariates. The disadvantage is that, by design, there is no overlap on this covariate across treatment groups.

-

Therefore, to “control for” this variable we must make stronger modeling assumptions because we will be forced to extrapolate our model out of the range of our data. To mitigate such extrapolations, one can limit analyses to observations that fall just above and below the threshold for assignment.

-

In general, the model fit just to the area of overlap may be considered more trustworthy.

-

-

"Fuzzy" discontinuity (as opposed to the "sharp" discontinuity): when the discontinuity is not so starkly defined.

-

this overlap arises from deviations from the stated assignment mechanism. If the reasons for these deviations are well defined (and measurable), then ignorability can be maintained by controlling for the appropriate characteristics.

-

Similarly, if the reasons for these deviations are independent of the potential outcomes of interest, there is no need for concern.

-

If not, inferences could be compromised by failure to control for important omitted confounders.

-

-

A counter-example that violates the assumption would be advertising “Free Shipping and Returns over $50” and attempting to measure the effect of offering free shipping on future customer loyalty. Why? This cut-off is known to individuals ahead of time and can be gamed. For example, perhaps less loyal are more skeptical of a company’s products and more likely to return, so they might intentionally spend more than $50 to change their classification and gain entrance to the treatment group

10.5 Estimating causal effects indirectly using instrumental variables

-

When ignorability is in doubt (because the dataset does not appear to capture all inputs that predict both the treatment and the outcomes), the method of instrumental variables (IV) can sometimes help.

-

In some situation, what we want to compare/estimate is not ready to be compared/estimated directly or can be truly compared/estimated due to the nature of the intervention or limitation in randomization. An example can be the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis, where subjects may not comply with the original assignment of randomization but are still treated as randomized assignment instead of acutal recieved intervention. ITT effect is not the estimate of true causal effect of intervention of interest, instead it is the estimate of the effect from the "process of treatment randomization". In order to estimate the true treatment effect of interest, instrument variable come play its role.

- An instrument is a variable thought to randomly induce variation in the treatment variable of interest.

-

Assumptions for instrumental variables estimation

-

Ignorability of the instrument: w.r.t the potential outcomes (both for the primary outcome of interest and the treat- ment variable)

- This is trivially satisfied in a randomized experiment (assuming the randomization was pristine). In the absence of a randomized experiment (or natural experiment) this property may be more difficult to satisfy and often requires conditioning on other predictors.

-

Nonzero association between instrument and treatment variable

- Although a nonzero association between the instrument and the treatment is an assumption of the model, fortunately this assumption is empirically verifiable.

-

Monotonicity: participant's behavior won't be affect by the true randomized intervention. Formally this is called the monotonicity assumption, and it need not hold in practice, though there are many situations in which it is defensible. [4]

-

Exclusion restriction: This assumption says for those children whose behavior would not have been changed by the encouragement (never-watchers and always-watchers) there is no effect of encouragement on outcomes.

- The exclusion restriction forces the potential outcomes to be the same for those whose viewing would not be affected by the encouragement.

- The effect of watching for the “induced watchers” is equivalent to the intent-to-treat effect (encouragement effect over the whole sample) divided by the proportion induced to view

-

In addition, the model assumes no interference between units (the stable unit treat- ment value assumption) as with most other causal analyses

-

-

Wald estimate: ITT estimate / ratio of participants to whom the intervention has effect

- This causal estimates apply only to the “induced watchers", i.e. it only applies to those the invention would have effect

- We are estimating (a special case of) what has been called a local average treatment effect (LATE).

-

The ITT effect may be of more interest in real-world. However, the intent- to-treat effect only parallels a true policy effect if in the subsequent policy implementation the compliance rate remains unchanged.

- It is recommended to estimate both the intent-to-treat effect and the local average treatment effect to maximize what we can learn about the intervention.

10.6 Instrumental variables in a regression framework

-

Model setting

\begin{align} y_i & = \beta_0 + \beta_1 T_i + \epsilon_i\ T_i & = \gamma_0 + \gamma_1 z_i + v_i \end{align}

where $z$ is the instrumental variable, $T$ is the treatment.

- The first assumption is that $z_i$ is uncorrelated with both $\epsilon_i$ and $ν_i$, which translates informally into the ignorability assumption and exclusion restriction (here often expressed informally as “the instrument only affects the outcome through its effect on the treatment”).

- The correlation between $z_i$ and $t_i$ must be nonzero (parallel to the monotonicity assumption from the previous section).

-

Without the assumption of exclusion restriction of instrument variable, true treatment effect is not identifiable:

\begin{align} y & = \beta_0 + \beta_1 T + \beta_2 z + error\ T& = \gamma_0 + \gamma_1 z + error \end{align}

-

$T$ is observational instead of being randomly assigned ($z$ is randomly assigned)[5], in general it can be correlated with the erorr in the first equation; thus we can't simply estimate $\beta_1$ by fitting a regression of $y$ on $T$ and $z$

-

By replacing $T$ in the first equation with second equation, we get

$$y = (\beta_0 + \beta_1\gamma_0) + (\beta_1\gamma_1 + \beta_2)z + error$$- Let $\delta_0 = \beta_0 + \beta_1\gamma_0$ and $\delta_1 = \beta_1\gamma_1 + \beta_2$, which are the regression coefficient from regressing $y$ on $z$, we then get $\beta_1 = (\delta_1 - \beta_2)/\gamma_2$

- It can be seen that without knowing $\beta_2$, $\beta_1$ isn't identifiable. And only under the exclusion restricion assumption, $\beta_2 = 0$ and $\beta_1 = \delta_1/\gamma_1$

-

-

Two-sage least squares

- The Wald estimate can be used but this method is more general; the difference from the Wald estimate is that, in the second

lm, predicted treatment is used as the predictor instead of the instrumental variable. - The first step is to regress the “treatment” variable on the randomized instrument

- Then make predicted values of the treatment and plug them into the equaiton of predicting the outcome of $y$

- the coefficient on the predicted treatment variable is the estimate of the causal effect of treatment of interest

fit.2a <- lm (watched ~ encouraged) watched.hat <- fit.2a$fitted fit.2b <- lm (y ~ watched.hat) coef.est coef.se (Intercept) 20.6 3.9 watched.hat 7.9 4.9 n = 240, k = 2 residual sd = 13.3, R-Squared = 0.01 - The Wald estimate can be used but this method is more general; the difference from the Wald estimate is that, in the second

-

Addjusting for covariates and standard error estimate

# put same set of adjustment variable in two stages fit.3a <- lm (watched ~ encouraged + pretest + as.factor(site) + setting) watched.hat <- fit.3a$fitted fit.3b <- lm (y ~ watched.hat + pretest + as.factor(site) + setting) display (fit.3b)- the standard-error calculation is complicated because we cannot simply look at the second regression in isolation.

- To adjust the standard error to account for the uncertainty in both stages of the model. The adjusted standard errors are calculated as the square roots of the diag- onal elements of $(X^tX)^{-1}\hat{\sigma}^2_{TSLS}$, where $\hat{\sigma}^2_{TSLS}$ is calculated using the residuals from an equation predicting the outcome from original design matrix using the two-stage least squares estimate of the coefficient, not the coefficient that would have been obtained in a least squares regression of the outcome on watched.

fit.3b <- lm (y ~ watched.hat+pretest+as.factor(site)+setting, x=TRUE) X.adj <- fit.2$x X.adj[,"watched.hat"] <- watched residual.sd.adj <- sd (y - X.adj %*% coef(fit.3b)) se.adj <-se.coef(fit.3b)["watched.hat"]*residual.sd.adj/sigma.hat(fit.3b)

-

Performing two-stage least squares automatically using the

tslsfunctioniv1 <- tsls (postlet ~ regular, ~ encour, data=sesame) display (iv1)- where in the second equation it is assumed that the “treatment” (in econometric parlance, the endogenous variable) for which encour is an instrument is whatever predictor from the first equation that is not specified as a predictor in the second.

-

A single instrument cannot be used to identify more than one treatment variable. As a general rule, we need to use at least as many instruments as treatment variables in order for all the causal estimates to be identifiable.

-

A binary instrument cannot in general identify a continuous treatment or “dosage” effect (without further assumptions).

- In essence this is equivalent to a setting with many different treatments (one at each dosage level) but only one instrument— therefore causal effects for all these treatments are not identifiable (without further assumptions).

-

In practice an instrumental variables strategy potentially is more useful in the context of a natural experiment, that is, an observational study context in which a “randomized” variable (instrument) appears to have occurred naturally. E.g.

- The draft lottery in the Vietnam War as an instrument for estimating the effect of military service on civilian health and earnings,

- The weather in New York as an instrument for estimating the effect of supply of fish on their price,

- The sex of a second child (in an analysis of people who have at least two children) as an instrument when estimating the effect of number of children on labor supply.

-

Assessing the plausibility of the instrumental variables assumptions

-

As a first step, the “first stage” model (the model that predicts the treatment using the instrument) should be examined closely to ensure both that the instrument is strong enough and that the sign of the coefficient makes sense.

- If the association between the instrument and the treatment is weak, instrumental variables can yield incorrect estimates of the treatment effect even if all the other assumptions are satisfied.

- Another consequence of a weak instrument is that it exacerbates the bias that can result from failure to satisfy the monotonicity and exclusion restrictions.

-

The two primary assumptions of instrumental variables (ignorability, exclusion) are not directly verifiable, but in some examples we can work to make them more plausible.

-

-

Structural equation modeling is a family of methods of multivariate data analysis that are sometimes used for causal inference.

- Instrumental variables can be considered to be a special case of a structural equation model.

-

A structural equation model that tries to estimate many causal effects at once multiplies the number of assumptions required with each desired effect so that it quickly becomes difficult to justify all of them.

-

Other online blog post on this topic:

10.7 Identification strategies that make use of variation within or between groups

-

Sometimes repeated observations within groups or within individuals over time can provide a means for controlling for unobserved characteristics of these groups or individuals.

-

Difference-in-difference strategies additionally make use of another source of variation in outcomes, typically time, to help control for potential (observed and unobserved) differences across these groups.

- An important advantage of this strategy is that the units of observation (in this case, houses) need not be the same across the two time periods.

- The assumption needed with this strategy is a weaker than the (unconditional) ignorability assumption because rather than assuming that potential outcomes are the same across treatment groups, one only has to assume that the potential gains in potential outcomes over time are the same across groups (for example, exposed and unexposed neighborhoods).

- Panel data is a special case of difference-in-differences estimation occurs when the same set of units are observed at both time points. This is also a special case of the so-called fixed effects model that includes indicators for treatment groups and for time periods.

- A simple way to fit this model is with a regression of the outcome on an indicator for the groups, an indicator for the time period, and the interaction between the two.

- The coefficient on the interaction is the estimated treatment effect.

Chapter 23 Causal inference using multilevel models

23.1 Multilevel aspects of data collection

23.2 Estimating treatment effects in a multilevel observational study

23.3 Treatments applied at different levels

23.4 Instrumental variables and multilevel modeling

Chapter 25 Missing data imputation

Missing data in R and Bugs

25.1 Missing-data mechanisms

Missingness completely at random (MCAR)

- A variable is missing completely at random if the probability of missingness is the same for all units

- If data are missing completely at random, then throwing out cases with missing data does not bias your inferences.

Missingness at random (MAR)

- Amore general assumption, missing at random, is that the probability a variable is missing depends only on available (fully recorded variables) information.

- When an outcome variable is missing at random, it is acceptable to exclude the missing cases (that is, to treat them as NA’s), as long as the regression controls for all the variables that affect the probability of missingness.

- This missing-at-random assumption (a more formal version of which is sometimes called the ignorability assumption) in the missing-data framework is the basically same sort of assumption as ignorability in the causal framework.

- Both require that sufficient information has been collected that we can “ignore” the assignment mechanism (assignment to treatment, assignment to nonresponse).

Missingness not at random

Missingness that depends on unobserved predictors

- Missingness is no longer “at random” if it depends on information that has not been recorded and this information also predicts the missing values.

- If missingness is not at random, it must be explicitly modeled, or else you must accept some bias in your inferences.

Missingness that depends on the missing value itself

- The probability of missingness depends on the (potentially missing) variable itself.

- Censoring and related missing-data mechanisms can be modeled (as discussed in Section 18.5) or else mitigated by including more predictors in the missing-data model and thus bringing it closer to missing at random.

- Controlling for variables that may be predictive of missingness will probably somewhat correct the bias due to missing

- while it can be possible to predict missing values based on the other variables just as with other missing-data mechanisms, this situation can be more complicated in that the nature of the missing-data mechanism may force these predictive models to extrapolate beyond the range of the observed data.

General impossibility of proving that data are missing at random

- we generally cannot be sure whether data really are missing at random, or whether the missingness depends on unobserved predictors or the missing data themselves.

- The fundamental difficulty is that these potential “lurking variables” are unobserved—by definition—and so we can never rule them out.

- In practice, we typically try to include as many predictors as possible in a model so that the “missing at random” assumption is reasonable.

25.2 Missing-data methods that discard data

-

Complete-case analysis

- In the regression context, this usually means complete-case analysis: excluding all units for which the outcome or any of the inputs are missing.

- Problems with complete-case analysis

- If the units with missing values differ systematically from the completely observed cases, this could bias the complete-case analysis.

- If many variables are included in a model, there may be very few complete cases, so that most of the data would be discarded for the sake of a simple analysis.

-

Available-case analysis

- different aspects of a problem are studied with different subsets of the data.

- Problems with the approach

- different analyses will be based on different subsets of the data and thus will not necessarily be consistent with each other.

- if the nonrespondents differ systematically from the respondents, this will bias the available-case summaries.

- Available-case analysis also arises when a researcher simply excludes a variable or set of variables from the analysis because of their missing-data rates (sometimes called “complete-variables analyses”). In a causal inference context (as with many prediction contexts), this may lead to omission of a variable that is necessary to satisfy the assumptions necessary for desired (causal) interpretations.

-

Nonresponse weighting

- For instance, that only one variable has missing data. We could build a model to predict the nonresponse in that variable using all the other variables.

- The inverse of predicted probabilities of response from this model could then be used as survey weights to make the complete-case sample representative (along the dimensions measured by the other predictors) of the full sample.

- Limitations

- This method becomes more complicated when there is more than one variable with missing data.

- Moreover, as with any weighting scheme, there is the potential that standard errors will become erratic if predicted probabilities are close to 0 or 1.

25.3 Simple missing-data approaches that retain all the data

Simple deterministic imputation methods

-

Whenever a single imputation strategy is used, the standard errors of estimates tend to be too low.

- Why: We have substantial uncertainty about the missing values, but by choosing a single imputation we in essence pretend that we know the true value with certainty.

-

Mean imputation

- This strategy can severely distort the distribution for this variable, leading to complications with summary measures including, notably, underestimates of the standard deviation

- Moreover, mean imputation distorts relationships between variables by “pulling” estimates of the correlation toward zero.

-

Last value carried forward

- This is often thought to be a conservative approach (that is, one that would lead to underestimates of the true treatment effect). However, there are situations in which this strategy can be anticonservative.

-

Using information from related observations

- E.g. imput mother's income with father's

- This is a plausible strategy, although these imputations may propagate measurement error.

- we must consider whether there is any incentive for the reporting person to misrepresent the measurement for the person about whom he or she is providing information.

- E.g. imput mother's income with father's

-

Indicator variables for missingness of categorical predictors

- For unordered categorical predictors, a simple and often useful approach

-

Indicator variables for missingness of continuous predictors

- to include for each continuous predictor variable with missingness an extra indicator identifying which observations on that variable have missing data.

- Then the missing values in the partially observed predictor are replaced by zeroes or by the mean (this choice is essentially irrelevant).

- This strategy is prone to yield biased coefficient estimates for the other predictors included in the model because it forces the slope to be the same across both missing-data groups.

- Adding interactions between an indicator for response and these predictors can help to alleviate this bias (this leads to estimates similar to complete-case estimates).

- to include for each continuous predictor variable with missingness an extra indicator identifying which observations on that variable have missing data.

-

Imputation based on logical rules

- This type of imputation strategy does not rely on particularly strong assumptions since, in effect, the missing-data mechanism is known.

25.4 Random imputation of a single variable

Simple random imputation

random.imp <- function (a){

missing <- is.na(a)

n.missing <- sum(missing)

a.obs <- a[!missing]

imputed <- a

imputed[missing] <- sample (a.obs, n.missing, replace=TRUE)

return (imputed)

}

> earnings.imp <- random.imp (earnings)

-

This approach does not make much sense (compared with using regression model)—it ignores the useful information from all the other questions asked of these survey responses—but these simple random imputations can be a convenient starting point.

-

Zero coding and topcoding

- Topcoding: truncate large value and set it to an up limit value, it reduces the sensitivity of the results to the highest values

- By topcoding we lose information, but if the variable is to be catgoriezed later on, it won't affect the result

- The purpose of topcoding was not to correct the data—we have no particular reason to disbelieve the high responses—but rather to perform a simple transformation to improve the predictive power of the regression model.

- Topcoding: truncate large value and set it to an up limit value, it reduces the sensitivity of the results to the highest values

Using regression predictions to perform deterministic imputation

- A simple and general imputation procedure that uses individual-level information uses a regression to the nonzero values of earnings.

lm.imp.1 <- lm (earnings ~ male + over65 + white + immig + educ_r + workmos + workhrs.top + any.ssi + any.welfare + any.charity, data=SIS, subset=earnings>0) pred.1 <- predict (lm.imp.1, SIS) impute <- function (a, a.impute){ ifelse (is.na(a), a.impute, a) } earnings.imp.1 <- impute (earnings, pred.1) - the predicted values from the regression will tend to be less variable than the original data

Random regression imputation

- Put the uncertainty back into the imputations by adding the prediction error into the regression

pred.4.sqrt <- rnorm (n, predict (lm.imp.2.sqrt, SIS), sigma.hat (lm.imp.2.sqrt)) pred.4 <- topcode (pred.4.sqrt^2, 100) earnings.imp.4 <- impute (earnings.top, pred.4)

Predictors used in the imputation model

- For imputation The goal here is not causal inference but simply accurate prediction, and it is acceptable to use any inputs (e.g. intermediate variable for the variable under imputation) in the imputation model to achieve this goal.

Two-stage modeling to impute a variable that can be positive or zero

Matching and hot-deck imputation

-

for each unit with a missing $y$, find a unit with similar values of $X$ in the observed data and take its y value.

- This approach is also sometimes called “hot-deck” imputation (in contrast to “cold deck” methods, where the imputations come from a previously collected data source).

- Matching can be viewed as a nonparametric or local version of regression and can also be useful in some settings where setting up a regression model can be challenging.

-

More generally, one could estimate a propensity score that predicts the missingness of a variable conditional on several other variables that are fully observed, and then match on this propensity score to impute missing values.

25.5 Imputation of several missing variables

Routine multivariate imputation

- The direct approach to imputing missing data in several variables is to fit a multivariate model to all the variables that have missingness, thus generalizing the approach of Section 25.4 to allow the outcome $Y$ as well as the predictors $X$ to be vectors.

- The difficulty of this approach is that it requires a lot of effort to set up a reasonable multivariate regression model

Iterative regression imputation

-

A different way to generalize the univariate methods of the previous section is to apply them iteratively to the variables with missingness in the data.

-

If the variables with missingness are a matrix $Y$ with columns $Y_{(1)}, . . . , Y_{(K)}$ and the fully observed predictors are $X$, this entails first imputing all the missing $Y$ values using some crude approach (for example, choosing imputed values for each variable by randomly selecting from the observed outcomes of that variable); and then imputing $Y_{(1)}$ given $Y_{(2)}, . . . , Y_{(K)}$ and $X$; imputing $Y_{(2)}$ given $Y_{(1)}, Y_{(3)}, . . . , Y_{(K)}$ and $X$ (using the newly imputed values for $Y_{(1)}$), and so forth, randomly imputing each variable and looping through until approximate convergence.

-

Iterative regression imputation has the advantage that, compared to the full multivariate model, the set of separate regression models (one for each variable, $Y_{(k)}$) is easier to understand, thus allowing the imputer to potentially fit a reasonable model at each step.

-

it is easier in this setting to allow for interactions (difficult to do using most joint model specifications)

-

The disadvantage of the iterative approach is that the researcher has to be more careful in this setting to ensure that the separate regression models are consistent with each other.

- Even if such inconsistencies are avoided, the resulting specification will not in general correspond to any joint probability model for all of the variables being imputed.

25.6 Model-based imputation

Nonignorable missing-data models

Imputation in multilevel data structures

- general advice in this situation is to create two datasets, one with only individual-level data, and one with group-level data and do separate imputations within each dataset while using results from one in the other (perhaps iterating back and forth).

25.7 Combining inferences from multiple imputations

-

Rather than replacing each missing value in a dataset with one randomly imputed value, it may make sense to replace each with several imputed values that reflect our uncertainty about our imputation model

-

Multiple imputation does this by creating several (say, five) imputed values for each missing value, each of which is predicted from a slightly different model and each of which also reflects sampling variability.

-

After MI, analyze each imputed complete dataset and combine the individual inference results into one

-

For instance, suppose we want to make inferences about a regression coefficient, $β$. We obtain estimates $\hat{\beta}_m$ in each of the $M$ datasets as well as standard errors, $s_1, . . . , s_M$.

-

To obtain an overall point estimate, we take the average over the $M$ estimates

$$\hat{\beta} = \frac{1}{M}\sum_{i=1}^M \hat{\beta}_m$$ -

A final variance estimate is a combination of variaion within and between imputations

$$V_{\beta} = W + \left(1 + \frac{1}{M}\right)B,$$where $W = \frac{1}{M}\sum_{m=1}^M s^2_m$ and $B = \frac{1}{M-1}\sum_{m=1}^M(\hat{\beta}_m - \hat{\beta})^2$.

-

-

If missing data have been included in the main data analysis (as when variables $X$ and $y$ are given distributions in a Bugs model), the uncertainty about the missing data imputations is automatically included in the Bayesian inference, and the above steps are not needed.

Causal design patterns for data analysts

References

Gelman, Andrew and Hill, Jennifer (2006). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. ↩︎

In survey sampling, stratification refers to the procedure of dividing the population into disjoint subsets (strata), sampling separately within each stratum, and then combining the stratum samples to get a population estimate. Poststratification is the analysis of an unstratified sample, breaking the data into strata and reweighting as would have been done had the survey actually been stratified. Stratification can adjust for potential differences between sample and population using the survey design; poststratification makes such adjustments in the data analysis. ↩︎

As further clarification, consider two participants of a study for which ignorability holds. If we define the probability of treatment participation as $Pr(T = 1|X)$, then this probability must be equal for these two individuals. However, suppose there exists another variable, $w$, that is associated with treatment participation (conditional on $X)$ but not with the outcome (conditionalon $X$). We do not require that $Pr(T = 1| X,W)$ be the same for these two participants. ↩︎

In defining never-watchers and always-watchers, we assumed that there were no children who would watch if they were not encouraged but who would not watch if they were encouraged. ↩︎

which can be most of the cases where instrumental variables are used: the intervention of interest is not randomized or is only observed during the trial; while there was some truly randomized treatment which affects the observed intervention of interest. When the truly randomized treatment statisify the instrumental variable assumption, we can use it as IV to estimate the effect from the observed (intermediate) variable on the outcome. ↩︎