Model comparison methods

Model Comparison Methods

General background

-

A list of criteria that are thought to be important for model comparison that have been proposed including:

- falsifiability

- explanatory adequacy

- interpretability

- faithfulness

- ⭐ goodness of fit

- ⭐ complexity or simplicity

- ⭐ generalizability

-

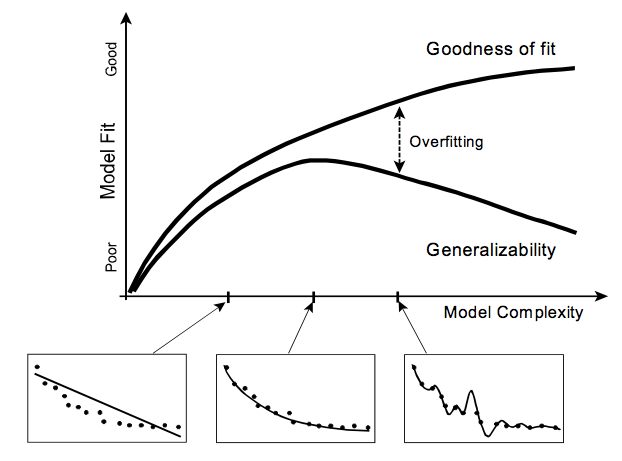

Modern statistical approaches to model comparison consider only the last three (goodness of fit, complexity, and generalizability).

- The goal of modeling is to identify the model that generated the data.

- Challenges: a) information in the data sample itself is frequently insufficient to narrow the choices down to a single model. b) data are inevitably confounded by random noise (sampling error, measurement error, etc.).

- Model selection is an inference game, with selection methods differing in their rules of play.

Notation and definition

- Formally, a model is defined as a parametric family of probability distributions. Each distribution is indexed by the model's parameter vector ${\boldsymbol w} = (w_1,\cdots,w_k)$ and corresponds to a population.

- The probability (density) function, denoted by $f({\boldsymbol y}|{\boldsymbol w})$, specifies the probability of observing data ${\boldsymbol y}$ given the parameter ${\boldsymbol w}$.

- Given the fixed data vector ${\boldsymbol y}$, $f({\boldsymbol y|w})$ becomes a function of ${\boldsymbol w}$ and is called the likelihood function denoted by ${\boldsymbol L(w)}$.

- Given a data sample, a model's descriptive adequacy is assessed by finding parameter values of the model that best fit the data in some defined sense. This procedure, called parameter estimation, is carried out by seeking the parameter vector ${\boldsymbol w}^*$ that maximizes the likelihood function $L({\boldsymbol w})$ given the observed data vector ${\boldsymbol y}$ $-$ a procedure known as maximum likelihood estimation.

Goodness-of-fit (maximized likelihood)

- The resulting maximized likelihood (ML) value, $L({\boldsymbol w}^*)$, defines a measure of the model's goodness of fit, which represents a model's ability to fit a particular set of observed data.

- Other examples of goodness-of-fit measures include the minimized sum of squared errors (SSE) between a model's predictions and observations, the proportion variance accounted for or otherwise known as the coefficient of determination $r^2$, and the mean squared error (MSE) defined as the square root of SSE divided by the number of observations.

- ML is a standard measure of goodness of fit, most widely used in statistics, and all of the model comparison methods discussed in the present chapter were developed using ML.

A good fit can be insufficient and misleading

$$\text{goodness of fit = fit to regularity + fit to noise}$$- Among a set of models under comparison, the scientist chooses the model that provides the best fit (i.e., highest ML value) to the observed data. The justification for this choice may be that the model best fitting the data is the one that does a better job than its rivals of capturing the underlying regularity.

- Such reasoning can be unfounded because a model can produce a good fit for reasons that have nothing to do with its ability to approximate the regularity of interest.

- Selecting among models using a goodness-of-fit measure would make sense if data were free of noise. In reality, however, data are not "pure" reflections of the population of interest.

- Any goodness-of-fit measure contains a contribution from the model's ability to fit random error as well as its ability to approximate the underlying regularity. The problem is that both quantities are unknown because when fitting a data set, we obtain the overall value of their sum, that is, a single goodness of fit.

Model complexity

- A model's ability to fit random noise is closely correlated with the complexity of the model.

- Complexity (or flexibility) refers to the property of a model that enables it to fit diverse patterns of data.

- A model with many parameters is more complex than a model with few parameters. Also, two models with the same number of parameters but different forms of the model equation (e.g., $y = w_1x + w_2 \text{ and } y = w_1x^{w_2}$) can differ in their complexity.

- Generally speaking, the more complex the model, the more easily it can absorb random noise, thus increasing its fit to the data without necessarily increasing its fit to the regularity.

- In fact one can always improve goodness of fit by increasing model complexity, such as adding more parameters.

Generalizability

-

A model's ability to fit the regularity in the data, represented by the first term on the right-hand side of the equation (1), defines its generalizability.

-

Generalizability, or predictive accuracy, refers to how well a model predicts the statistical properties of future, as yet unseen, samples from a replication of the experiment that generated the current data sample.

-

Statistically speaking, generalizability is defined in terms of a discrepancy function that measures the degree of approximation or dissimilarity between two probability distributions (Linhart & Zucchini, 1986).

-

When a model is evaluated against its competitors, the goal should be not to assess how much better it fits a single data sample, but how well it captures the process that generated the data.

$$\text{Generalizability} = E_T[D(f_T, f_M)]=\int D[f_T, f_M({\boldsymbol w^*(Y)})]f_T({\boldsymbol y})d{\boldsymbol y}$$where $D(f, g)$ is the discrepancy function between two distributions $f$ and $g$; the less one probability distribution approximates the other, the larger value of $D(f, g)$.

-

Generalizability is a mean discrepancy between the true model and the model of interest, averaged across all data that could possibly be observed under the true model.

-

Generalizability increases positively with complexity only up to the point where the model is optimally complex to capture the regularities in the data. Any additional complexity beyond this point will cause generalizability to diminish as the model begins to over-fit the data by absorbing random noise.

-

In short, a model must be sufficiently complex to capture the underlying regularity yet not too complex to cause it to over-fit the data and thus lose generalizability.

-

To reiterate, in model comparison, one would like to choose the model, among a set of competing models, that maximizes generalizability. Unfortunately, generalizability is not directly observable because noise always distorts the regularity of interest.

-

Generalizability, therefore, must be estimated from a data sample. It is achieved by weighting a model\textquoteright s goodness of fit relative to its complexity.

Model comparions methods

Measures of generalizability

-

AIC: (Akaike, 1973; Bozdogan, 2000): Akaike Information Criterion

-

BIC: (Schwarz, 1978): Bayesian Information Criterion

-

MDL: Minimum Description Length; Rissanen, 1983, 1996; Grunwald, 200; Hanse & Yu, 2001)

-

CV: cross-validation; (Stone 1974; Browne, 2000)

-

BMS: Bayesian model selection; (Kass & Raftery, 1995; Wasserman, 2000)

$$AIC=-2\ln L({\boldsymbol w}^*)+2k$$$$BIC=-2\ln L({\boldsymbol w}^*)+k\ln(n)$$$$MDL=-\ln L({\boldsymbol w}^*)+\frac{k}{2}\ln\left(\frac{n}{2\pi}\right)+\ln\int\sqrt{|I({\boldsymbol w})|}d{\boldsymbol w}$$$$CV=-\ln f({\boldsymbol y}_{val}|{\boldsymbol w}^*({\boldsymbol y}_{cal}))$$$$BMS=-\ln\int L({\boldsymbol w})\pi({\boldsymbol w})d{\boldsymbol w}$$where

$$L({\boldsymbol w}^*)\text{ is the natrual logarithm of the maximized likelihood};$$$$k \text{ is the number of parameter in the model};$$$$n \text{ is the sample size};$$$$\pi({\boldsymbol w})\text{ is the parameter prior density};$$$$I({\boldsymbol w})\text{ is the Fisher information matrix}.$$These comparison methods prescribe that the model minimizing the given criterion should be preferred.

-

Among the five comparison methods discussed above, BMS and MDL represent state-of-the-art techniques that will generally perform more accurately across a range of modeling situations than the other three criteria (AIC, BIC, CV).

-

The latter three are attractive given their ease of use, and are likely to perform adequately under certain circumstances. In particular, if the models being compared do differ in number of parameters and further, sample size is sufficiently large, then one may be able to use AIC or BIC with confidence instead of the more sophisticated BMS and MDL.

AIC, BIC, and MDL

-

For these three, the first term represents a lack of fit measure and the remaining terms represent a model complexity measure.

-

Each criterion defines complexity differently:

- AIC $-$ # of parameters;

- BIC $-$ # of parameters + sample size;

- MDL $-$ first two terms are similar to what BIC has, the additional last term accounts for the effect of complexity due to functional form (which is reflected through the Fisher informtion matrix $I({\boldsymbol w})$[1]

-

AIC was derived as a large sample approximation of the discrepancy between the true model and the fitted model in which the discrepancy is measured by the Kullback-Leiber distance (Kullback & Leibler, 1951). AIC purports to select the model, among a set of candidate models, that is closest to the truth in the Kullback-Leibler sense.

-

BIC has its origin in Bayesian statistics and seeks the model that is "most likely " to have generated the data in the Bayesian sense. BIC can be seen as a large sample approximation of a quantity related to BMS.

-

MDL: originated from algorithmic coding theory in computer science. The goal of MDL is to select the model that provides the shortest description of the data in bits. The more the model is able to compress the data by extracting the regularities or patterns in it, the better the model's generalizability because these uncovered regularities can then be used to predict accurately future data.

-

Given this additional sensitivity, MDL is expected to perform more accurately than its two competitors. The price to pay for MDL's superior performance is the computational challenge in its calculation; the evaluation of the integral term generally requires use of numerical integration techniques.

Cross-validation (CV)

-

CV is a sampling-based method in which generalizability is estimated directly from the data without an explicit consideration of model complexity.

-

The method works as follows.

- First, the observed data are split into two sub-samples of equal size.

- We then fit the model of interest to the first, calibration sample (${\boldsymbol y}_{cal}$) and find the best-fitting parameter values, denoted by ${\boldsymbol w}^*({\boldsymbol y}_{cal})$.

- With these values fixed, the model is fitted to the second, validation sample (${\boldsymbol y}_{val}$). The resulting fit of the model to the validation data ${\boldsymbol y}_{val}$ defines the model's generalizability estimate.

-

CV's ease of use is offset by the unreliability of its generalizability estimate, especially for small sample sizes.

-

Unlike AIC and BIC, CV takes into account the functional form effects of complexity, although the implicit nature of CV makes it difficult to discern how this is achieved.

Bayesian model selection (BMS)

- BMS, a sharper version of BIC, is defined as the minus marginal likelihood.

- The marginal likelihood is the probability of the observed data given the model, averaged over the entire range of the parameter vector and weighted by the parameter prior density $\pi({\boldsymbol w})$. As such, BMS aims to select the model with the highest mean likelihood of the data.

- The often cited Bayes factor} (Kass & Raftery, 1995) is a ratio of marginal likelihoods between a pair of models being compared.

- BMS does not yield an explicit measure of complexity though complexity is taken into account and is hidden in the integral. It is through the integral that the functional form dimension of complexity, as well as the number of parameters and the sample size, is reflected.

- It is also the integral that makes it non-trivial to implement BMS.

Relation to generalized likelihood ratio test (GLRT)

-

Although the generalized likelihood ratio test (GLRT) is often used to test the adequacy of a model in the context of another model, it is not an appropriate method for model comparison.

-

The GLRT is definded as

$$G^2=-2\ln \frac{ML_0}{ML_a}\sim \chi^2_p \text{ under null}$$where $\frac{ML_0}{ML_a}$ is the ratio of the maximized likelihoods of two nested models, model null is nested within model alternative and $p$ is the difference of number of parameters in two models under comparison.

-

When the null hypothesis is retained (i.e., the p-value does not exceed the alpha level), the conclusion is that the reduced model null provides a sufficiently good fit to the observed data and therefore the extra parameters of the full model alternative unnecessary. If the null hypothesis is rejected, one concludes that model null is inadequate and the extra parameters are necessary to account for the observed data.

-

Several crucial differences between GLRT and the five model comparison methods:

- First, GLRT does not assess generalizability, which is the goal of model comparison. Rather, it is a hypothesis testing method that simply judges descriptive adequacy of a given model. Even if the null hypothesis is retained under GLRT, the result does not necessarily indicate that model null is more likely to be correct or generalize better than model alternative, or vice versa.

- Second, GLRT requires the nestedness assumption hold of the two models being tested. In contrast, no such assumptions is required for the five comparison methods, making them much more versatile.

- Third, GLRT was developed in the context of linear regression models with normally-distributed error, further restricting its use.

- GLRT is also inappropriate for testing non-linear models and models with non-normal error. Again, no such restrictions are imposed on the preceding model comparison methods.

Comments for real work

- A good method should be able to identify the true model (i.e., the one that generated the data) 100% of the time. Any deviations from perfect recovery reveal a bias in the selection method.

- It is importance to account for all relevant dimensions of complexity in model comparison. When comparing two models that have same number of parameters but different functional formats, methods only accout for number of parameters, like AIC, may be less favorable to those also account for the functional form like MDL.

- Model comparison is an inference problem. The quality of the inference depends strongly on the characteristics of the data (e.g., sample size, experimental design, type of random error) and the models themselves (e.g., model equation, parameters, nested vs non-nested). For this reason, it is unreasonable to expect a selection method to perform perfectly all the time.

- When using any of these selection methods, we advise that the results be interpreted in relation to the other criteria important in model selection

- They are not the arbiters of truth. Like any such tool, they are blind to the quality of the data and the plausibility of the models under consideration.

Bias-variance trade-off

- Common question for data science interviews

- “Bias” and “variance” are two ways of looking at the same thing. (“Bias” is conditional, “variance” is unconditional.) [2]

To grasp this, note that the matrix $I({\boldsymbol w})$ is defined in terms of the second derivative of the log-likelihood function $\ln L({\boldsymbol w})$, the value of which depends upon the form of the model equation,for instance, whether $y=w_1x+w_2 \text{ or } y=w_1x^{w_2}$ ↩︎

“Bias” and “variance” are two ways of looking at the same thing. (“Bias” is conditional, “variance” is unconditional.) ↩︎