Survival Analysis

Survival analysis general

Definitions of survival endpoints

Guidance for Industry Clinical Trial Endpoints for the Approval of Cancer Drugs and Biologics

- OS: overall survival. time from randomization to death from any cause, and is measured in ITT population.

- PFS: time from randomization until objective tumor progression or death.

- TTP: time to progression. time from randomization until objective rumor progression; doesn't include deaths

- DFS: disease free survival. time from randomization until recurrence of tumor or death for any cause. usually used in the adjuvant setting after definitive surgery or rediotherapy

- ORR: objective response rate. proportion of patients with tumor size reduction of a predefined amount for a minimum time period.

Counting process representation

- The process $Y_i(t)$ is equal to 1 while a person is known to be at risk and 0 otherwise ($Y_i(t) = I(V_i < t \le T_i)$, where $V_i$ is the time of entering the study) and the process $N_i(t)$ denotes the number of observed events by time $t$, here simply given by $N_i(t) = I(V_i < t \le T_i, \delta_i=1)$

- Defining $dN_i(t) = N_i(t) - N_i(t-)$, observation of the event at time $t$ can then be represented by $dN_i(t)= 1$, that is, the counting process for individual $i$ increments by 1 at that time.

Censoring

- Independent censoring: A basic assumption that the information that a patient has not been censored at a certain time point does not carry any information about his/her prognosis beyond that time point.

- The assumption can be weakened to conditionally independent censoring, i.e. independent censoring within a group of patients with a certain set of characteristics, defined by the covariates available in the study data base.

- Administrative censoring: censoring at a certain calendar time due to the end of study, is a common example of independent censoring, as the censoring mechanism is not related to individual patient prognosis.

The intensity

- Definition

\begin{array} & \lambda_i(t) & \approx P(\text{event in} (t, t+dt)|\text{past at time } t-)/dt\ & = P(dN_i(t) = 1|H_i(t-))/dt \end{array}

-

where $H_i(t-) = (N_i(s), Y_i(s), Z_i(s), s

-

More formally, $\lambda_i(t) = \lim_{\Delta\rightarrow 0} P(dN_i(t) = 1 | H_i(t-)/\Delta t)$

-

Hazard function

$$ \lambda(t) = -\frac{d\log S(t)}{dt} $$ -

When no time-dependent covariates are considered in $H_i(t)$, the intensity simply equals to the hazard.

-

When there is only one type of event, there is an one-to-one correspondce between hazard function $\lambda(t)$ and $S(t)$, and thereby with the cumulative risk $F(t) = 1-S(t)$.

- While, if there are other events competing with the event of interest, $\lambda(t)$ is a transition hazard (or cause-specific hazard) from state 0 to state 1. In this case, a one-to-one correspondence between the single cause-specific hazard and the absolute probabilities no longer exists.

-

Interpretation of the intentisty

- Given the information that is available so far for the subject (i.e. the subject is still observed to be at risk at time $t$), what is the probability per time unit that the subject experiences the event in the next little time interval from $t$ to $t + dt$?

- The intensity gives a dynamical description of how events occur over time and, in this description, all aspects of the past observed for the subject up to time t may be taken into account, such as (time-dependent) covariates and, possibly, previous events.

-

Other notes

- the hazard function (in contrast to the survival function) can still be studies under censoring mechanism since it relies exclusively on the information on the individuals still at risk (assuming the independent censoring assumption to hold)

- One of the greatest strengths of intensity-basedmodels is that one can examine the effects of both baseline covariates (ie, information available at time of entry into the study) and time-dependent covariates that are updated during follow-up.

- Using a hazard regression model is that it “corrects for non-independent censoring” in the sense that regression coefficients are estimated consistently even if censoring depends on covariates, as long as these covariates are included as predictors in the hazard model (==how to understand this?==)

Hazrd models

-

Estimating the hazard non-parametrically requires some sort of smoothing. What may be estimated non-parametrically is the cumulative hazard $\Lambda(t) = \int_0^t\lambda(u)du$. This may be done with the Nelson-Aalen estimator

$$ \hat{\Lambda}(t) = \int_0^t \frac{dN(u)}{Y(u)} du= \sum_{i: T_i\le t} \frac{\delta_i}{Y(T_i)}, $$where $Y(t) = \sum_i Y_i(t)$ and $N(t) = \sum_i N_i(t)$.

- This is an increasing step function with steps at each observed event time, the step size at $t$ being inversely proportional to the number $Y(t)$ at risk.

- The approximate "local slope" of $\hat{\Lambda}$ at $t$ reflects the hazard at that time.

Cox PH model

Time-dependent covariates and immortal time bias

- Immortal time bias: including in the model the value of time-dependent covarite(s) collected after the time of event outcome.

- It is crucial that only information reflecting covariate values observed before time t (ie, from the “past” at t) is used to define the value of a variable $Z(t)$ at time $t$.

- A common example is to group patients at time t = 0 according to the use of drugs or treatments at any time during the follow-up even if many might have started their use only at some time after time $t = 0$ (“ever treated” vs “never treated”)

- Another example can be the study of total number doses recevied and survial outcome. A patient generally receive more treatment doses when he/she lives longer.

- In all of the above cases, creation of a well-defined time-dependent covariate where $Z(t)$ does not depend on any of $Z(s), N(s)$, or $Y(s)$ for any $s > t$ repairs the bias.

Competing risk model

Prediction using hazard models

- Communication is usually easier in terms of the absolute risk, that is, the probability of the event occurring in some interval or, more generally, the probability of being in a certain state by time t.

Prediction in the absence competing risks

-

Without time-dependent covarites

$$ F(t|Z) = 1 - S(t|Z) = 1 - \exp(-\Lambda(t|Z)) $$ -

From $t=0$ onwards

- Using the Cox model

- If the focus is on one particular value ts (eg, the 5-year survival in cancer), a surprisingly robust estimator of $S(t_s|Z)$ can often be obtained by applying administrative censoring at $t_s$ and using a simple Cox model with the effects $\beta$ fixed in time provided $t_s$ is not too large.

- Direct modeling

- If there were no censoring before ts, the survival probability $S(t_s|Z)$ could be directly estimated by models for the binary outcome $I(T^* > t_s)$

- Using the Cox model

-

Dynamic prediction

- Prediction at a later time $t_{\text{pred}} + t_s$ built on some intermediate time $t_{\text{pred}}$

- the prediction is based on a new model using the data of the individuals still alive at $t_{\text{pred}}$ is known as dynamic prediction

- the approach of building new models using the individuals at risk at $t_{\text{pred}}$ is known as landmarking

- Prediction at a later time $t_{\text{pred}} + t_s$ built on some intermediate time $t_{\text{pred}}$

-

Prediction exploiting time-dependent covariates

- Using the landmarking method, where the history of a time-dependent covariate up to $t_{\text{pred}}$ is summarized in to a single statistic (e.g. the last observation) and used as a time-fixed covariate in the prediction model. Such model can only be used as a working model.

- Using joint models of longitudinal and survial outcomes and estimate survival prob. by conditioning on the history of $Z(t)$ at $t_{\text{pred}}$ and $T^*\ge t_{\text{pred}}$.

Prediction with competing risks

-

Ignoring competing risk(s) will produce an upwards biased estimate of the absolute risk (cumulative incidence) because by treating competing events as censorings, one pretends that the target population is one where the competing events are not operating and therefore neglects the fact that subjects who have died from competing causes can no longer experience the event of interest.

-

In such a situation it is necessary to estimate the absolute risk. This is the probability of experiencing event 1 at a certain time point and it depends not only on the hazard of this event but also on the probability of having survived up to this time point. And as this survival probability depends on the hazards of all events, this implies it is necessary also to estimate the intensity of the competing events.

¶ F_1(t|Z) = \int_0^t S(u|Z)d\Lambda_{01}(u|Z) = \int_0^t\exp(-\Lambda_{02}(u|Z) - \Lambda_{01}(u|Z))d\Lambda_{01}(u|Z)\label{pred_comp}where $\Lambda_{02}(t|Z)$ is the cumulative hazard for competing events.

- Without covariates, the estimator obtained by plugging-in Nelson-Aalen estimates for the cumulative hazard in {eq}

pred_compis known as the Aalen-Johansen estimator. - The intuition behind the middle term of {eq}

pred_compis that the integrand, the survival probability, $S(u|Z)$ of surviving to time $u$, times the conditional probability, $dΛ_{01}(u|Z)$ of dying from cause 1 at time $u$ given survival till $u$, is the (unconditional) probability of dying from cause 1 at time $u$; $F_1(t | Z)$, the probability of dying from cause 1 by time $t$ is then obtained as the sum (integral)

- Without covariates, the estimator obtained by plugging-in Nelson-Aalen estimates for the cumulative hazard in {eq}

-

It's also possible to directly model $F(t|Z)$, e.g., using the Fine and Gray regression model.

-

For constant hazard $\lambda$, thus exponentially distributed survival times,

-

the MLE of $\lambda$ is given by

$$ \hat{\lambda} = \frac{d}{\sum_{i=1}^dx_i} $$- $d$: total number of events

- $x_i$: event time for $i$th event

-

If an estimate $\hat{\pi}$ of the event rate in a period of length $l$ is given, $\lambda$ is estimated by

$$ \hat{\lambda} = \frac{-\log(1-\hat{\pi})}{l} $$

-

-

with the median survival time estimate of $\hat{m}$, the estimated hazard can be estimated as

$$ \hat{\lambda} = \frac{log(2)}{\hat{m}} $$- Thus, the estimate of hazard ratio is the reciprocal of the ratio of median survival time between two groups:

Sample size calculation [1]

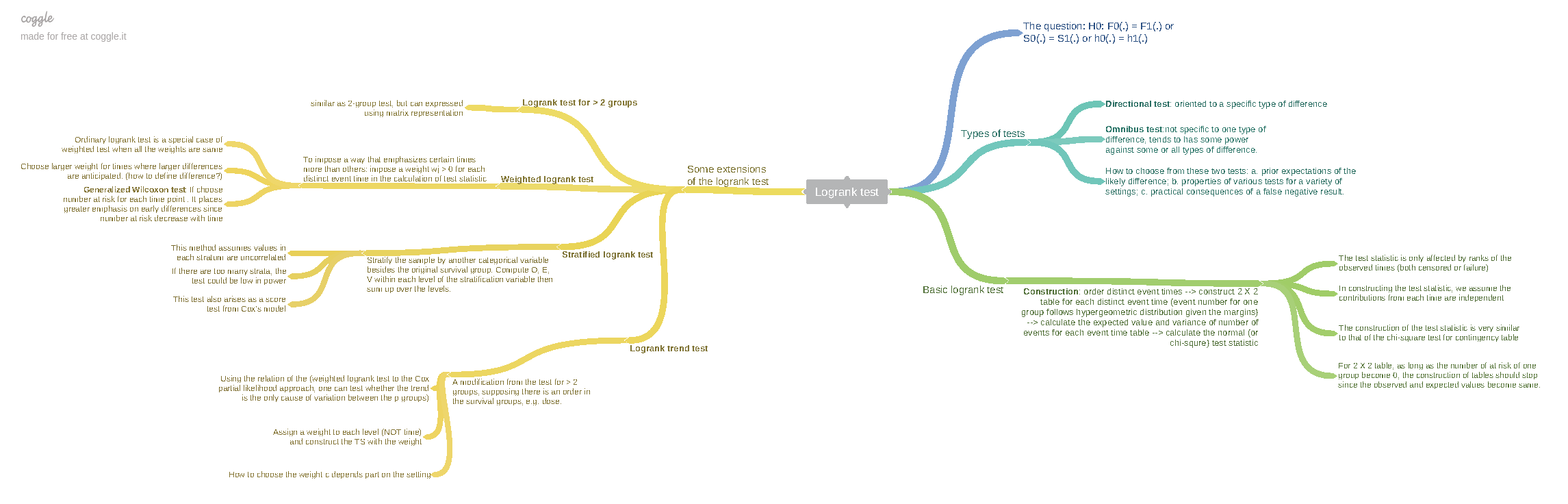

Log-rank test

-

Test statistic for LR test

$$ LR = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^d\left(I_{2i} - \frac{n_{2i}}{n_{1i} + n_{2i}}\right)}{\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^d\frac{n_{1i}n_{2i}}{(n_{1i} + n_{2i})^2}}} $$- $d$ is the total number of events

- $n_{1i}$ and $n_{2i}$ are number of patients at risk in group 1 and 2, respectively, when the $i$th event occurred.

- $I_{2i}$ = 1 if the $i$th event was in group 2 and = 0 otherwise

-

Non-parametric test as it doesn’t depend on the observed survival times but only depends on the number of patients who were at risk at the $i$th event

-

For fixed $d$ and let the patients be recruited until $d$ events were observed. Then the LR test statistic is approximately normally distributed

$$ LR \sim N(\sqrt{d}\frac{\sqrt{r}}{1 + r}\log(\omega), 1) $$- $\omega$ is the true hazard ratio

- $r = n_2/n_1$

Total number of events $\rightarrow$ total sample size

- Power calculation is based on total number of events not number of patients

-

The first step is to determine the required number of events

$$ d_f = \frac{\left(\Phi^{-1}(1-\alpha/2)+ \Phi^{-1}(1-\beta)\right)^2}{r/(1+r)^2(\log(\omega_1))^2} $$- $H_1: \omega = \omega_1$

- Two-sided $\alpha$, power = $1-\beta$

-

From total number of events to total sample size

$$ n = n_{f_1}+n_{f_2} = n_{f_1}(1+r) = d_f/\phi \Rightarrow n_{f_1} = \frac{d_f}{\phi*(1+r)} $$-

$\phi$ is the combined probability of an event in the two treatment groups:

$$ \phi = (\phi_{\lambda_1} + r\phi_{\lambda_2})/(1 + r) $$-

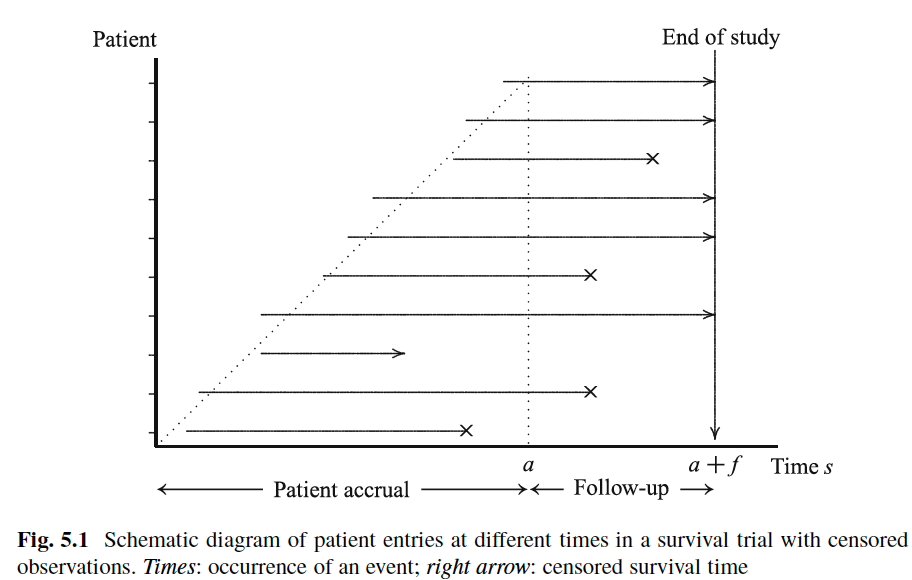

Assuming constant hazard rate (or exponential survival time) and patients enter the trial uniformly over the recruitment time period $a$

\begin{align} \phi_{\lambda_j(s)} &=& P_{\lambda_j}(X < C)\ &=& \int_{\max{0, s-a}}^s P_{\lambda_j}(X<c|C=c)g(c)dc\ &=& \int_{\max{0, s-a}}^s(1-\exp(-\lambda_jc))\frac{1}{a}dc \end{align}

$\Rightarrow$

$$ \phi_{\lambda_j(s)} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \frac{s}{a} - \frac{1-\exp(-\lambda_js)}{\lambda_ja} &&\text{if } s\le a\\ 1 - \exp(-\lambda_js)\frac{\exp(\lambda_ja) - 1}{\lambda_ja} &&\text{if } s>a \end{array} \right. $$ -

Thus, by the end of trial (i.e. $s = a+f > a$)

$$ \phi_{\lambda_j}(a + f) =1-\exp(-\lambda_j(a+f))\frac{\exp(\lambda_ja)-1}{\lambda_ja} $$

-

-

with increasing length $a + f$ of the study, the required total sample size decreases and, given any $a$, it converges to $d$.

-

References

Wassmer, Gernot and Brannath, Werner (2016). Group sequential and confirmatory adaptive designs in clinical trials. ↩︎