Propensity Score Methods & Implementation

Propensity score methods in observational data analysis (theoretical part) [1]

Randomized Controlled Trials Versus Observational Studies

The Potential Outcomes Framework and Average Treatment Effects

- What is the potential outcomes framework??

- The average treatment effect (ATE) is defined to be is $E[Y_i(1)-Y_i(0)]$

- A related measure of treatment effect is the average treatment effect for the treated (ATT; Imbens, 2004). The ATT is defined as $E[Y(1)-Y(0)|Z = 1]$

The Propensity Score And Propensity Score Methods

1. Propensity Score Matching

- Propensity score matching entails forming matched sets of treated and untreated subjects who share a similar value of the propensity score (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983a, 1985).

- Propensity score matching allows one to estimate the ATT (Imbens, 2004).

- Once a matched sample has been formed, the treatment effect can be estimated by directly comparing outcomes between treated and untreated subjects in the matched sample.

- With binary outcomes, the effect of treatment can also be described using the relative risk or the NNT (Austin, 2008a, 2010; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983a).

- Schafer and Kang (2008) suggest that, within the matched sample, the treated and untreated subjects should be regarded as independent.

- In contrast to this, Imbens (2004) suggests that, when using a matched estimator, the variance should be calculated using a method appropriate for paired experiments. I argue that the propensity score matched sample does not consist of independent observations.

- The lack of independence in the propensity score matched sample should be accounted for when estimating the variance of the treatment effect.

- The analysis of a propensity score matched sample can mimic that of an RCT

- In the context of an RCT, one expects that, on average, the distribution of covariates will be similar between treatment groups. However, in individual RCTs, residual differences in baseline covariates may exist between treatment groups.

- Regression adjustment results in increased precision for continuous outcomes and increased statistical power for continuous, binary, and time-to-event outcomes (Steyerberg, 2009).

- Propensity score matching can be combined with additional matching on prognostic factors or regression adjustment (Imbens, 2004; Rubin & Thomas, 2000).

Methods for forming matched pairs

- one must choose between matching without replacement and matching with replacement (Rosenbaum, 2002).

- When matching with replacement is used, variance estimation must account for the fact that the same untreated subject may be in multiple matched sets (Hill & Reiter, 2006).

- A second choice is between greedy and optimal matching (Rosenbaum, 2002).

- An alternative to greedy matching is optimal matching, in which matches are formed so as to minimize the total within-pair difference of the propensity score.

- optimal matching did no better than greedy matching in producing balanced matched samples.

- criteria for selecting untreated subjects whose propensity score is “close” to that of a treated subject.

- There are two primary methods for this: nearest neighbor matching and nearest neighbor matching within a specified caliper distance (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1985)

- If multiple untreated subjects have propensity scores that are equally close to that of the treated subject, one of these untreated subjects is selected at random. It is important to note that no restrictions are placed upon the maximum acceptable difference between the propensity scores of two matched subjects.

- Nearest neighbor matching within a specified caliper distance is similar to nearest neighbor matching with the further restriction that the absolute difference in the propensity scores of matched subjects must be below some prespecified threshold (the caliper distance).

- If no untreated subjects had propensity scores that lay within the specified caliper distance of the propensity score of the treated subject, that treated subject would not be matched with any untreated subject. The unmatched treated subject would then be excluded from the resultant matched sample.

- there is no uniformly agreed upon definition of what constitutes a maximal acceptable distance.

- Based on these results, there are theoretical arguments for matching on the logit of the propensity score, as this quantity is more likely to be normally distributed, and for using a caliper width that is a proportion of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score.

- For instance, if the variance of the logit of the propensity score in the treated subjects is the same as the variance in the untreated subjects, using calipers of width equal to 0.2 of the pooled standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score will eliminate approximately 99% of the bias due to the measured confounders.

- It was suggested that researchers use a caliper of width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score as this value (or one close to it) minimized the mean squared error of the estimated treatment effect in several scenarios.

-

Alternatives to one-to-one pair matching when matching on the propensity score:

- many-to-one (M: l) matching, M untreated subjects are matched to each treated subject.

- Full matching (Gu & Rosenbaum, 1993; Hansen, 2004; Rosenbaum, 1991) involves forming matched sets consisting of either one treated subject and at least one untreated subject or one untreated subject and at least one treated subject.

-

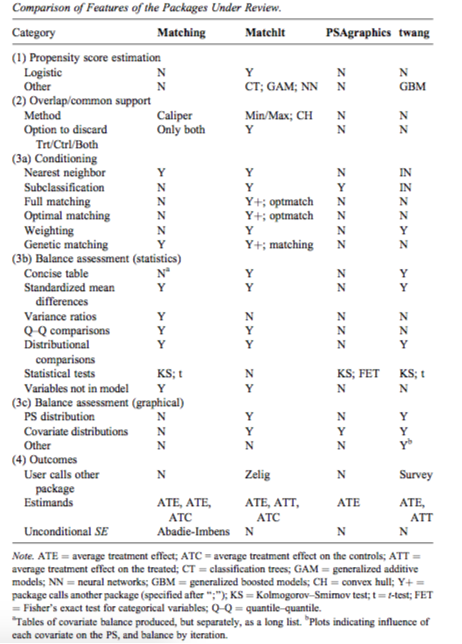

In R, the Matching (Sekhon, in press), Matchlt (Ho, Imai, King, & Stuart, 2011), and Optmatch (Hansen & Klopfer, 2006) packages allow one to implement a variety of different matching methods.

2. Stratification on the Propensity Score

- Stratification on the propensity score involves stratifying subjects into mutually exclusive subsets based on their estimated propensity score.

- A common approach is to divide subjects into five equal-size groups using the quintiles of the estimated propensity score.

- Rosenbaum and Rubin (1984) extended this result to stratification on the propensity score, stating that stratifying on the quintiles of the propensity score eliminates approximately 90% of the bias due to measured confounders when estimating a linear treatment effect. Increasing the number of strata used should result in improved bias reduction, although the marginal reduction in bias decreases as the number of strata increases (Cochran, 1968; Huppler Hullsiek & Louis, 2002).

- Stratification on the propensity can be conceptualized as a meta-analysis of a set of quasi-RCTs.

- In general, stratum-specific estimates of effect are weighted by the proportion of subjects who lie within that stratum. Thus, when the sample is stratified into K equal-size strata, stratum-specific weights of 1/K are commonly used when pooling the stratum-specific treatment effects, allowing one to estimate the ATE (Imbens, 2004). The use of stratum-specific weights that are equal to that proportion of treated subjects that lie within each stratum allow one to estimate the ATT (Imbens, 2004). A pooled estimate of the variance of the estimated treatment effect can be obtained by pooling the variances of the stratum-specific treatment effects.

- As with matching, within-stratum regression adjustment may be used to account for residual differences between treated and untreated subjects (Imbens, 2004; Lunceford & Davidian, 2004).

3. Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting Using the Propensity Score

-

Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) uses weights based on the propensity score to create a synthetic sample in which the distribution of measured baseline covariates is independent of treatment assignment.

-

Weights can be defined as

$$\omega_i = \frac{Z_i}{e_i} + \frac{(1-Z_i)}{1-e_i},$$where $e_i$ is the propensity score and $Z_i$ is the indicator of treatment assignment, where $Z_i=1$ for treated and 0 for control.

-

A subject's weight is equal to the inverse of the probability of receiving the treatment that the subject actually received. Thus, for control patients, the weight is $1/(1-e_i)$

-

An estimate of the ATE is

$$\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{Z_iY_i}{e_i} - \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{(1-Z_i)Y_i}{1-e_i},$$where $n$ denotes the number of subjects

-

When used in this context, IPTW is part of a larger family of causal methods known as marginal structural model (Hernan, Brumback, & Robins, 2000, 2002).

-

variance estimation must account for the weighted nature of the synthetic sample, with robust variance estimation commonly being used to account for the sample weights (Joffe et al., 2004).

-

The weights may be inaccurate or unstable for subjects with a very low probability of receiving the treatment.

-

However, using weights equal to

$$\omega_{i, ATT} = Z_i + \frac{(1-Z_i)e_i}{1-e_i}$$allows one to estimate the ATT, whereas the use of weights equal to

$$\omega_{i, ATC} = \frac{Z_i(1-e_i)}{e_i} + (1-Z_i)$$allows one to estimate the average effect of treatment in the controls (Morgan & Todd, 2008).

Derivation of the IPTW (from Causal inference in statistics a primer Section 3.6)

-

Notation:

- $Y$: outcome

- $X$: intervention of interest

- $Z$: confounders

-

Objective:

$$P(y|\text{do}(x=\text{yes [or no]}))$$ -

Derivation:

$$ \begin{array}{ll} P(y|\text{do}(x)) & = \sum_z P(y|X = x, Z = z)P(Z=z)\\ & = \sum_z \frac{P(y|X = x, Z = z)P(X=x|Z=z)P(Z=z)}{P(X=x|Z=z)}\\ & = \sum_z\frac{P(Y= y, X = x, Z = z)}{P(X=x|Z=z)} \end{array} $$- Each case $(Y = y, X = x, Z = z)$ in the population should boost its probability by a factor equals to $1∕P(X = x|Z = z)$. (Hence the name “Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting”; here it is the probability of getting $X = x$ [0 or 1], it is the 1/propensity score (PS) for the treated subjects but 1/(1 - PS) for the untreated ones)

4. Covariate Adjustment Using the Propensity Score

- This method assumes that the nature of the relationship between the propensity score and the outcome has been correctly modeled.

Comparison of the Different Propensity Score Methods

- Propensity score matching, stratification on the propensity score, and IPTW differ from covariate adjustment using the propensity score in that the three former methods separate the design of the study from the analysis of the study

- As Rubin (2001) notes, when using regression modeling, the temptation to work toward the desired or anticipated result is always present. Another difference between the four propensity score approaches is that covariate adjustment using the propensity score and IPTW may be more sensitive to whether the propensity score has been accurately estimated (Rubin, 2004).

See Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models Section 10.3 for another discussion of creation and using propensity score in causal inferenence.

Balance Diagnostics

- The true propensity score is a balancing score: conditional on the true propensity score, the distribution of measured baseline covariates is independent of treatment assignment.

- In strata of subjects that have the same propensity score, the distribution of measured baseline covariates will be the same between treated and untreated subjects.

- If, after conditioning on the propensity score, there remain systematic differences in baseline covariates between treated and untreated subjects, this can be an indication that the propensity score model has not been correctly specified.

- For IPTW this assessment involves comparing treated and untreated subjects in the sample weighted by the inverse probability of treatment.

-

Comparing the similarity of treated and untreated subjects in the matched sample should begin with a comparison of the means or medians of continuous covariates and the distribution of their categorical counterparts between treated and untreated subjects.

-

For a continuous covariate, the standardized difference is defined as

$$d = \frac{(\bar{X}_{treatment} - \bar{X}_{control})}{\sqrt{\frac{s^2_{treatment} + s^2_{control}}{2}}}$$where $\bar{X}_{treatment}$ and $\bar{X}_{control}$ denote the sample mean of the covariate in treated and untreated subjects, respectively, whereas $s^2$ denote the sample variance of the covariate.

-

For dichotomous variables, the standardized difference is defined as

$$d = \frac{(\hat{p}_{t} - \hat{p}_{c})}{\sqrt{\frac{\hat{p}_t(1-\hat{p_t}) + \hat{p}_c(1-\hat{p_c})}{2}}}$$where $\hat{p}$ denote the prevalence or mean of the dichotomous variable

-

The standardized difference compares the difference in means in units of the pooled standard deviation.

-

it is not influenced by sample size and allows for the comparison of the relative balance of variables measured in different units.

-

a standard difference that is less than 0.1 has been taken to indicate a negligible difference in the mean or prevalence of a covariate between treatment groups (Normand et al., 2001).

-

the entire distribution of baseline covariates, not just means and prevalences, should be similar between treatment groups in the matched sample. Therefore, higher order moments of covariates and interactions between covariates should be compared between treatment groups

-

graphical methods such as side-by-side boxplots, quantile-quantile plots, cumulative distribution functions, and empirical nonparametric density plots can be used to compare the distribution of continuous baseline covariates between treatment groups in the propensity score matched sample (Austin, 2009b).

-

One proceeds in an iterative fashion until systematic differences in observed baseline covariates between treated and untreated subjects have either been eliminated or reduced to an acceptable level. It is important to note that at each step of the iterative process, one is not guided by the statistical significance of the estimated regression coefficients in the propensity score model (assuming one is using a logistic regression model).

-

Some authors have suggested that the comparison of baseline covariates may be complemented by comparing the distribution of the estimated propensity score between treated and untreated subjects in the matched sample (Ho et al., 2007).

-

This approach may be useful for determining the common area of support or the degree of overlap in the propensity score between treated and untreated subjects.

-

This approach is insufficient for determining whether an important variable has been omitted from the propensity score model or for assessing whether the propensity score model has been correctly specified (Austin, 2009b).

-

This approach has been criticized by several authors for two reasons (Imai et al., 2008; Austin, 2008b, 2009b).

- First, significance levels are confounded with sample size.

- Second, Imai et al. suggested that balance is a property of a particular sample and that reference to a superpopulation is inappropriate.

- For these reasons, the use of statistical significance testing to assess balance in propensity score matched samples is discouraged.

-

this statistic provides no information as to whether the propensity score model has been correctly specified

Variable Selection For The Propensity Score Model

-

Possible sets of variables for inclusion in the propensity score model include the following:

-

all measured baseline covariates,

-

all baseline covariates that are associated with treatment assignment,

-

all covariates that affect the outcome (i.e., the potential confounders)

-

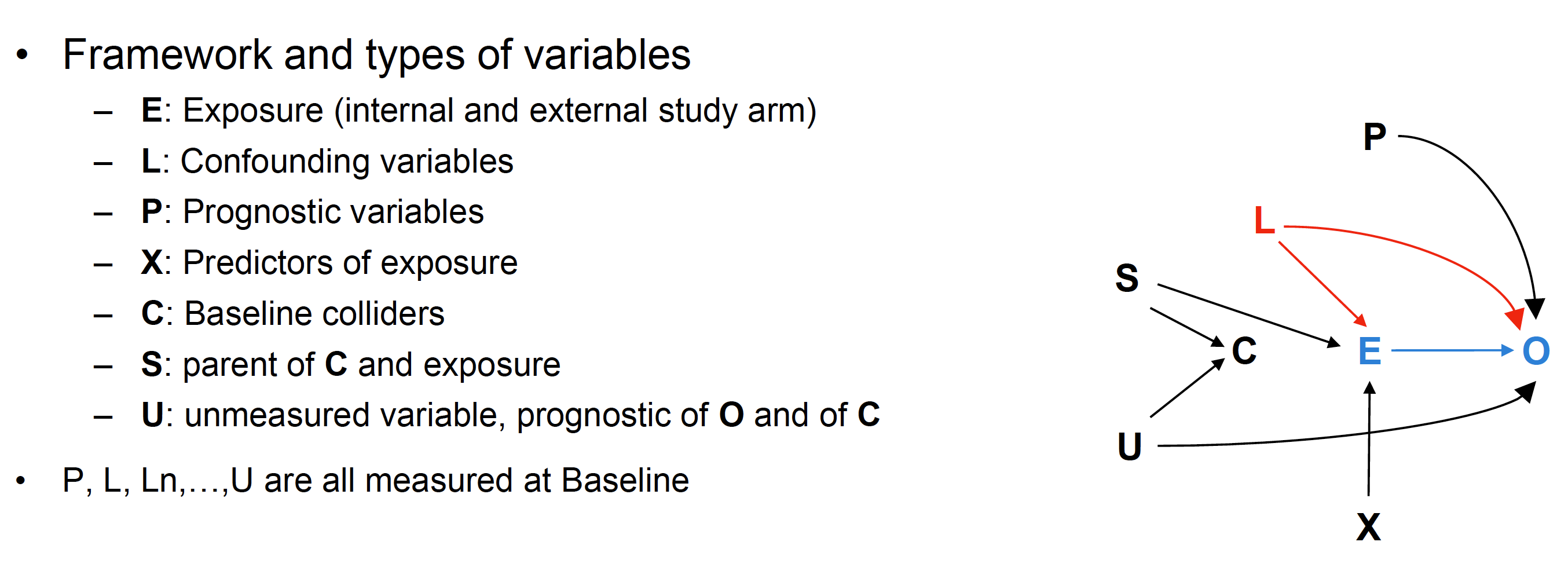

✔️ According to a presentation shared in a seminar, model inference performs best when the PS model includes L or L + P as shown in the DAG below

- Adding X to L does not harm but has a strong cost in precision and power

- PS based on L + Colliders (C), or only on X, or automatic variable selection of predictors of exposure is NOT recommended

-

-

there are theoretical arguments in favor of the inclusion of only those variables that affect treatment assignment.

-

✔️ It was shown that there were merits to including only the potential confounders or the true confounders in the propensity score model.

- using these two propensity score models did not result in the introduction of additional bias but resulted in estimates of treatment effect with greater precision.

-

✔️ variables that do not affect exposure but that affect the outcome (P) should always be included in the propensity score model. Furthermore, they noted that including variables that affect exposure but not the outcome (X) will increase the variance of the estimated treatment effect without a concomitant reduction in bias.

-

Therefore, in many settings, it is likely that one can safely include all measured baseline characteristics in the propensity score model.

-

✔️ Finally, one should stress that the propensity score model should only include variables that are measured at baseline and not post-baseline covariates that may be influenced or modified by the treatment.

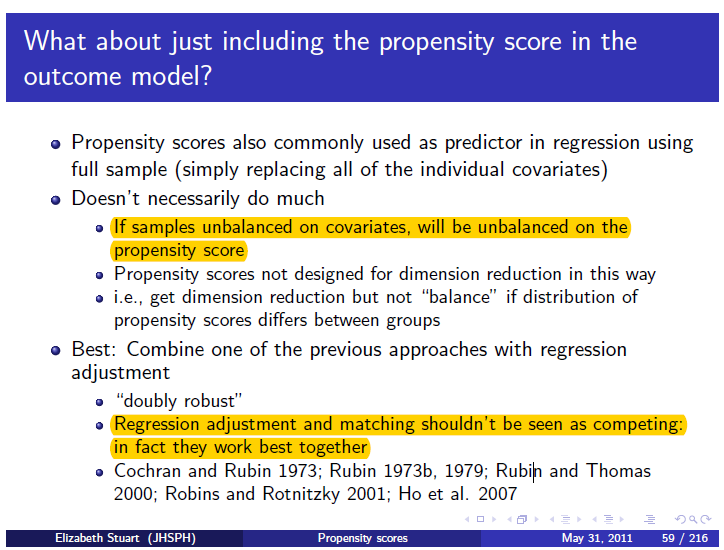

Propensity Score Methods Versus Regression Adjustment

Conditional Versus Marginal Estimates of Treatment Effect

- A conditional treatment effect is the average effect of treatment on the individual. A marginal treatment effect is the average effect of treatment on the population. A measure of treatment effect is said to be collapsible if the conditional and marginal effects coincide.

- Propensity score methods allow for estimation of the marginal treatment effect (Rosenbaum, 2005).

- Assuming that both the outcome regression model and the propensity score model were correctly specified, it follows that propensity score methods should result in conclusions similar to those obtained using linear regression adjustment.

- However, when the outcome is either binary or time-to-event in nature and if the odds ratio or the hazard ratio is used as the measure of treatment effect, then, even in the absence of confounding, the marginal and conditional estimates of the treatment effect need not coincide

- In part, study design and the analytic plan should reflect which treatment effect is more meaningful in a given context.

- researchers should note that both RCTs and propensity score methods allow one to estimate marginal treatment effects.

Regression Adjustment Versus Propensity Score Methods: Practical Concerns

- First, it is simpler to determine whether the propensity score model has been adequately specified than to assess whether the regression model relating treatment assignment and baseline covariates to the outcome has been correctly specified.

- it is much more difficult to determine whether the regression model relating treatment selection and baseline covariates to the outcome has been correctly specified.

- Second, these methods allow one to separate the design of the study from the analysis of the study.

- when using regression adjustment, the outcome is always in sight, and the researcher is faced with the subtle temptation to continually modify the regression model until the desired association has been achieved (Rubin, 2001).

- Third, there may be increased flexibility when outcomes (when binary or time-to-event in nature) are rare and treatment is common (Braitman & Rosenbaum, 2002).

- When outcomes are either binary or time-to-event in nature, prior research has suggested that at least 10 events should be observed for every covariate that is entered into a regression model (Peduzzi, Concato, Feinstein, & Holford, 1995; Peduzzi, Concato, Kemper, Holford, & Feinstein, 1996).

- Fourth, one can explicitly examine the degree of overlap in the distribution of baseline covariates between the two treatment groups.

-

When using regression-based approaches, it may be difficult to assess the degree of overlap between the distribution of baseline covariates for the two groups.

-

Propensity Score Analysis in R: A Software Review (implementation part)

Four basic steps in matching

-

Estimation of propensity scores That is the probability of getting treatment for each unit (various classification methods can be used to estimate this probability)

-

Assessment of overlap The support of estimated propensity scores in the treatment and control groups must share common support (units from different arm should have nonzero probability of receiving bot the treatment and control)

-

Assessment of balance Balance in confounding variables, measured by mean, std, standardized mean difference, and variance ratio (see below); Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance is another way to measure the balance $$d = \frac{\bar{X}_T - \bar{X}_C}{s_{\text{pooled}}}, r = \frac{s_T^2}{s_C^2}$$ $$s_{\text{pooled}} = \sqrt{\frac{(N_T-1)s_T^2 + (N_C - 1)s_C^2}{N_T + N_C - 2}}$$

-

Estimation of the average causal effect and its standard error i. average treatment effect (ATE): average effect for everyone in population $$ \begin{array}{ll} ATE & = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N Y_i(1) - Y_i(0)\\ & = \pi[E(Y(1) - Y(0)|T = 1)] + (1-\pi)[E(Y(1) - Y(0)|T = 0)], \end{array} $$ where $\pi$ is the proportion of subjects in the treatment group ii. **average treatment effect on the treated (ATT)**: average treatment effect for those in the treatment group $$ATT = \frac{1}{N_t}\sum_{i=1}^{N_t} [Y_i(1) - Y_i(0) | T_i = 1],$$ where $Y_i(0)$ is hypothetic and not observed in reality. iii. average treatment effect on the control (ATC)

- ATE is more general than ATT as it refers to the entire study cohort while ATT only refers to those who are treated. In the ideal case of randomized control trial, ATE = ATT because we assume $$E[Y(0)|T = 1] = E[Y(0) | T = 0]$$ $$E[Y(1)|T = 1] = E[Y(1) | T = 0]$$

- These are very strong assumptions which are commonly violated in observational studies and therefore the ATT and the ATE are not expected to be equal. Notice that if only the baselines are equal, you can still get an ATT through simple differences: $\mathrm{E}[Y(1)|T=1] - \mathrm{E}[Y(0)|T=0]$.

Comparison of packages in R

Propensity score matching using MatchIt in R

- General syntax:

matchit(trt ~ covariates, data, method = 'nearest', ratio = 1) - Different options for

method: a. Exact matching: matches each treated with a control unit that has exactly the same values on each covariate (not ideal for cases where there are many covariates that can take a large range of values) b. Subclassification: breaks the data set into subclasses such that the distributions of the covariates are similar in each subclass c. Nearest neighbor: matches a treated unit to a control unit(s) that is closest in terms of a distance measure such as a logit (PS calculated using logistic regression) d. Optimal matching: focuses on minimizing the average absolute distance across all matched pairs (depends onoptmatchpackage) e. Genetic matching: uses a computationally intensive genetic search algorithm to match treatment and control units (depending on Matching package) f. Coarsened exact matching: matches on a covariate while maintaining the balance of other covariates (supposed to work well for multicategory treatments, determining blocks in experimental designs, and evaluating extreme counterfactuals)

[Earlier note](./attachments/Propensity score methods in observational data analysis.pdf)

References

Austin, Peter C (2011). An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. ↩︎

Brookhart, M Alan and Wyss, Richard and Layton, J Bradley and St{"u}rmer, Til (2013). Propensity score methods for confounding control in nonexperimental research. ↩︎