Non-inferiority/equivalence/superiority test basics

Superiority, equivalence and non-inferiority [1]

-

Both non-inferiority and superiority tests are examples of directional (one-sided) tests and their power and sample size could be calculated using the Two-Sample T-Test procedure. A non-inferiority test tests that the treatment mean is not worse than the reference mean by more than the equivalence margin. The actual direction of the hypothesis depends on the response variable being studied.

- In the case of lower values are better. The hypotheses are arranged so that rejecting the null hypothesis implies that the treatment mean is no more than a small amount above the reference mean.

- Margin of non-inferiority. This is a tolerance value that defines the magnitude of the amount that is not of practical importance. This may be thought of as the largest change from the baseline that is considered to be trivial. The absolute value is shown to emphasize that this is a magnitude. The sign of the value will be determined by the specific design that is being used.

-

The statistical test will be set up so that if the null hypothesis is rejected, the conclusion will be that the new treatment is non-inferior. To assess whether the null hypothesis can be rejected (or, in this case, that the non-inferiority margin is met) it is usual practice to perform a one-sided hypothesis test at the α level of significance. One-sided tests are used here because our alternative hypothesis is examining whether the new product is the same (non-inferior to) or better than the existing product.

-

We are not interested in the hypothesis that the new product is significantly worse than the existing product. By not rejecting the non-inferiority hypothesis test, we will have accomplished this goal. This test will be identical to calculating a two-sided 100(1 – $\alpha$) percentage confidence interval for the difference between the two products $(X – Y)$. If the upper bound on the confidence interval of the difference between $X$ and $Y$ is less than $D$ (the prespecified non-inferiority margin), you can conclude that the standard product is more efficacious than the new product by no more than $D$. Then the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the non-inferiority of the new product.

-

Example

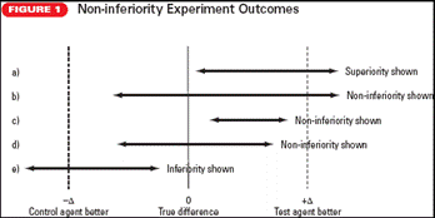

a. Superiority shown: The confidence bound of $(X – Y)$ does not include the 0 difference line, and the confidence bound exceeds the upper margin of non-inferiority. The result shows the superiority of $Y$. This result is identical to that of a hypothesis comparing $X$ and $Y$ in which superiority of $Y$ is shown.

b. Non-inferiority shown: Non-inferiority is shown because the lower bound of $(X – Y)$ crosses the 0 difference line; although the upper bound does exceed the upper non-inferiority boundary, but the lower bound does not cross the lower non-inferiority boundary.

c. Non-inferiority shown: Here non-inferiority is shown because the confidence bounds for $(X – Y)$ are totally within the non-inferiority boundaries.

d. Non-inferiority shown: Non-inferiority is shown because, although the confidence bounds for $(X – Y)$ cross the 0 line, the lower bound does not cross the lower non-inferiority boundary.

e. Inferiority shown: The lower bound of the confidence interval of $(X – Y)$ crosses the lower boundary of the inferiority margin.

-

In summary, the non-inferiority margin must be chosen to test $Y$ (new treatment) as being superior to placebo and non-inferior to $X$ (standard treatment). The value of the non-inferiority margin should be chosen as the maximum acceptable difference between $X$ and $Y$.

Understanding Equivalence and Noninferiority Testing[2]

-

Effective standards of care have been developed in many clinical settings, and it is increasingly more difficult to develop new therapies with higher efficacy than the standard of care.

-

These (new) therapies offer advantages such as fewer side effects, lower cost, easier application, or fewer drug interactions.

-

The objective in testing for equivalence/noninferiority is precisely the opposite (to traditional hypothesis testing), and it requires modifications to the traditional hypotheses testing methods.

-

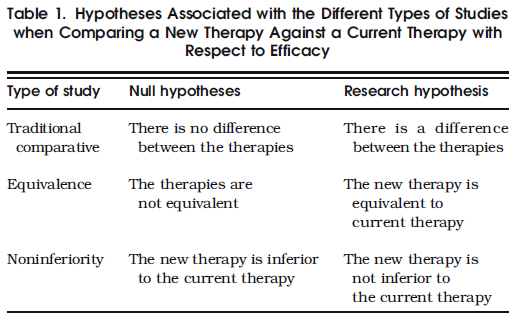

In hypotheses testing, the research or alternative hypothesis represents what the study aims to show.

- In essence, the null and research hypotheses in testing equivalence are simply those of a traditional comparative study

reversed. For noninferiority studies, the research hypothesis is that the new therapy is either equivalent or superior to the current therapy (Table 1).

- In essence, the null and research hypotheses in testing equivalence are simply those of a traditional comparative study

reversed. For noninferiority studies, the research hypothesis is that the new therapy is either equivalent or superior to the current therapy (Table 1).

-

The term equivalent is not used here in the strict sense, but rather to mean that the efficacies of the two therapies are close enough so that one cannot be considered superior or inferior to the other. This concept is formalized in the definition of a constant called the equivalence margin. The equivalence margin defines a range of values for which the efficacies are “close enough” to be considered equivalent.

-

In practical terms, the margin is the maximum clinically acceptable difference that one is willing to accept in return for the secondary benefits of the new therapy.

-

In summary, the equivalence of a new therapy is established when the data provide enough evidence to conclude that its efficacy is within $δ$ units from that of the current therapy.

-

If the equivalence margin is set to zero, $δ=0$, then the problem simplifies to a traditional one-sided superiority test.

-

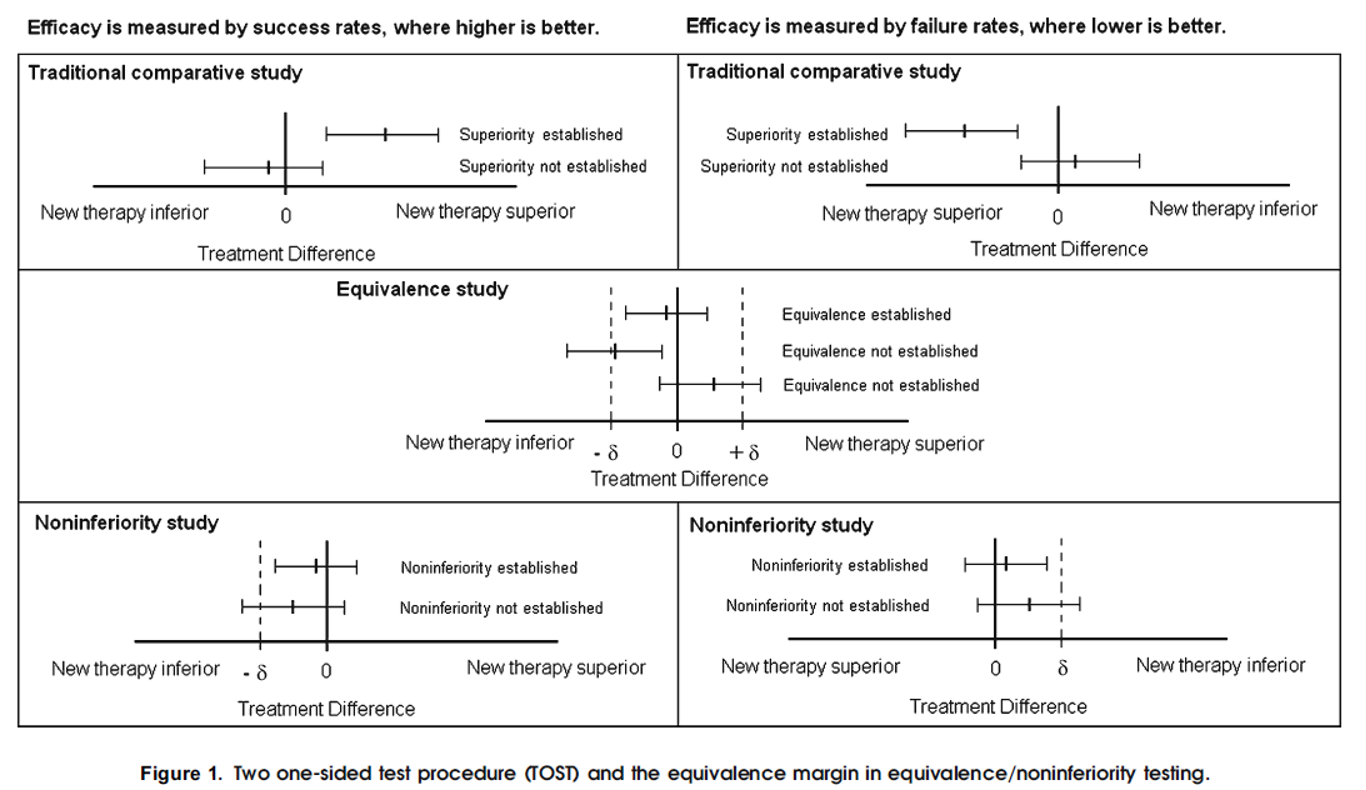

The simplest and most widely used approach to test equivalence is the two one-sided test (TOST) procedure. Using TOST, equivalence is established at the $α$ significance level if a $(1–2α) × 100\%$ confidence interval for the difference in efficacies (new – current) is contained within the interval $(-δ, δ)$

- The reason the confidence interval is $(1–2α) × 100\%$ and not the usual $(1- α) × 100\%$ is because this method is tantamount to performing two one-sided tests. Thus, using a 90% confidence interval yields a 0.05 significance level for testing equivalence.

-

Noninferiority is established, at the α significance level, if the lower limit of a $(1–2α) × 100\%$ confidence interval for the difference (new – current) is above $-δ$ (when higher is better) (Fig. 1)

- Non-inferiority tests are one-sided tests

-

Since an equivalence test is tantamount to applying two traditional one-sided tests, a p-value can be reported as the larger of the two p-values of each of the one-sided tests. (to make sure if one test is significant then both tests are significant $\rightarrow$ to establish the research hypothesis)

-

An equivalence/noninferiority study should be designed to minimize the possibility that a new therapy that is found to be equivalent/noninferior to the current therapy can be nonsuperior to a placebo.

-

One way to minimize this possibility is to choose a value of the equivalencemargin based on themargin of superiority of the current therapy against the placebo. This margin of superiority can be estimated from previous studies. In noninferiority testing, a ommonpractice is to set the value of $δ$ to a fraction, $f$, of the lower limit of a confidence interval of the difference between the current therapy and the placebo obtained from a meta analysis. The smaller the value of $f$, the more difficult the establishment of equivalence/noninferiority of the new therapy.

-

The choice of f is a matter of clinical judgment governed by the maximum loss of efficacy one is willing to accept in return for nonefficacy advantages of the new therapy

-

When the outcome is mortality, the FDA has suggested a value of f of 0.50.

-

Note that the smaller differences commonly observed in ITT have the opposite effect when testing equivalence/noninferiority. ITT makes it easier to establish equivalency/noninferiority and is considered anticonservative. The FDA requires the reporting of both (ITT and PP) types of analyses