[book] Fundamentals of Clinical Trials (4th edition)#

A study note of [Friedman et al., 2015]

Chapter 5 Basic Study Design#

Sound scientific clinical investigation almost always demands that a control group be used against which the new intervention can be compared. Randomization is the preferred way of assigning participants to control and intervention groups.

Most trials use the so-called parallel design. That is, the intervention and control groups are followed simultaneously from the time of allocation to one or the other.

Exceptions to the simultaneous follow-up are historical control studies. These compare a group of participants on a new intervention with a previous group of participants on standard or control therapy.

A modification of the parallel design is the cross-over trial, which uses each participant at least twice, at least once as a member of the control group and at least once as a member of one or more intervention groups.

Another modification is a withdrawal study, which starts with all participants on the active intervention and then, usually randomly, assigns a portion to be followed on the active intervention and the remainder to be followed off the intervention.

Factorial design trials employ two or more independent assignments to intervention or control.

Controls may be on placebo, no treatment, usual or standard care, or a specified treatment.

Randomized control and nonrandomized concurrent control studies both assign participants to either the intervention or the control group, but only the former makes the assignment by using a random procedure.

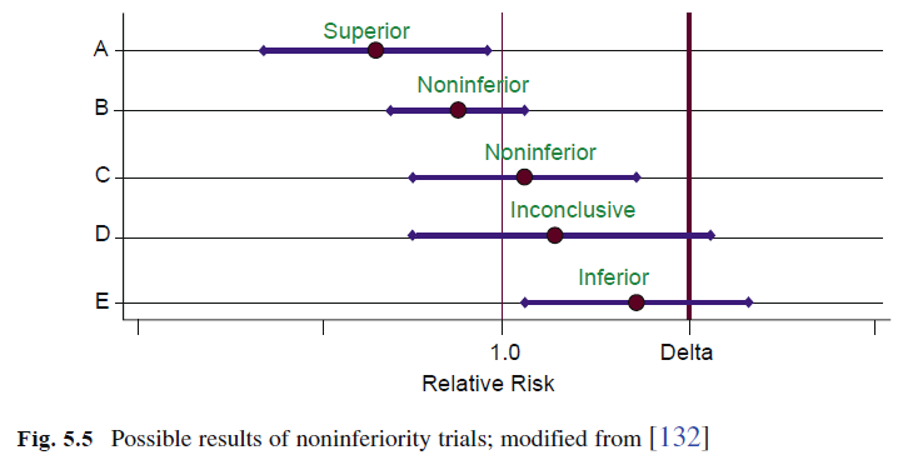

there are superiority trials and equivalence or noninferiority trials. A superiority trial, which for many years was the typical kind of trial, assesses whether the new intervention is better or worse than the control. An equivalence trial would assess if the new intervention is more or less equal to the control. A noninferiority trial evaluates whether the new intervention is no worse than the control by some margin, delta (d).

In both of these latter cases, the control group would be on a treatment that had previously been shown to be effective, i.e., have an active control.

5.1 Randomized control trials#

There are three advantages of the randomized design over other methods for selecting controls: i. First, randomization removes the potential of bias in the allocation of participants to the intervention group or to the control group. ii. The second advantage, somewhat related to the first, is that randomization tends to produce comparable groups; that is, measured as well as unknown or unmeasured prognostic factors and other characteristics of the participants at the time of randomization will be, on the average, evenly balanced between the intervention and control groups. iii. The third advantage of randomization is that the validity of statistical tests of significance is guaranteed.

The process of randomization makes it possible to ascribe a probability distribution to the difference in outcome between treatment groups receiving equally effective treatments and thus to assign significance levels to observed differences.

Not all clinical studies can use randomized controls, e.g. for rare diseases. In such an instance, only case–control studies might be possible.

5.2 Non-randomized concurrent control study#

The major weakness of the nonrandomized concurrent control study is the potential that the intervention group and control group are not strictly comparable.

Even for large studies that could detect most differences of real clinical importance, the uncertainty about the unknown or unmeasured factors is still of concern.

5.3 Historical controls and databases#

If an investigator is already of the opinion that the new intervention is beneficial, then she would most likely consider any restriction on its use unethical.

In addition, participants may be more willing to enroll in a study if they can be assured of receiving a particular therapy or intervention.

Finally, since all new participants will be on the new intervention, the time required to complete recruitment of participants for the trial will be cut approximately in half.

Typically, historical control data can be obtained from two sources. i. First, control group data may be available in the literature. These data are often undesirable because it is difficult, and perhaps impossible, to establish whether the control and intervention groups are comparable in key characteristics at the onset. ii. Second, data may not have been published but may be available on computer files or in medical charts.

Limitations of historical control studies

They are particularly vulnerable to bias.

An improvement in outcome for a given disease may be attributed to a new intervention when, in fact, the improvement may stem from a change in the patient population or patient management.

Time trend of disease rate may not be separable from the true treatment effect when using historical control.

Shifts in diagnostic criteria for a given disease due to improved technology can cause major changes in the recorded frequency of the disease and in the perceived prognosis of the subjects with the disease.

common concern about historical control designs is the accuracy and completenes swith which control group data are collected.

The role of historical control studies

In some special cases where the diagnosis of a disease is clearly established and the prognosis is well known or the disease highly fatal, a historical control study may be the only reasonable design.

The primary reasons have been the speed and lesser cost of such analyses, compared with clinical trials.

In addition, databases likely represent a much broader population than the typical clinical trial and can therefore complement clinical trial findings.

5.4 Cross-over designs#

The cross-over design allows each participant to serve as his own control. In the simplest case, namely the two period cross-over design, each participant will receive either intervention or control (A or B) in the first period and the alternative in the succeeding period. The order in which A and B are given to each participant is randomized.

Depending on the duration of expected action of the intervention (for example, drug half-life), a wash-out period may be used between the periods.

The appeal of the cross-over design to investigators is that it allows assessment of how each participant does on both A and B. Since each participant is used twice, variability is reduced because the measured effect of the intervention is the difference in an individual participant’s response to intervention and control (smaller sample size needed).

To use the cross-over design, however, a fairly strict assumption must be made; the effects of the intervention during the first period must not carry over into the second period.

This assumption should be independent of which intervention was assigned during the first period and of the participant response. In many clinical trials, such an assumption is clearly inappropriate, even if a wash-out is incorporated.

Obviously, a fatal event cannot serve as the primary response variable in a crossover trial. Cross-over trials should be limited

to those situations with few losses of study participants.

The basic appeal of the cross-over design is to avoid between-participant variation in estimating the intervention effect, thereby requiring a smaller sample size.

Only if there is substantial evidence that the therapy has no carryover effects, and the scientific community is convinced by that evidence, should a crossover design be considered.

5.5 Withdrawal studies#

A number of studies have been conducted in which the participants on a particular treatment for a chronic disease are taken off therapy or have the dosage reduced. The objective is to assess response to discontinuation or reduction. This design may be validly used to evaluate the duration of benefit of an intervention already known to be useful.

Withdrawal studies have also been used to assess the efficacy of an intervention that had not conclusively been shown to be beneficial in the long term.

One serious limitation of this type of study is that a highly selected sample is evaluated. Only those participants who physicians thought were benefiting from the intervention were likely to have been on it for several months or years. Anyone who had major adverse effects from the drug would have been taken off and, therefore, not been eligible for the withdrawal study. Thus, this design can overestimate benefit and underestimate toxicity.

Another drawback is that both participants and disease states change over time.

5.6 Factorial design#

In the simple case, the factorial design attempts to evaluate two interventions compared to control in a single experiment.

A concern with the factorial design is the possibility of the existence of interaction and its impact on the sample size. Interaction means that the effect of intervention X differs depending upon the presence or absence of intervention Y, or vice versa. It is more likely to occur when the two drugs are expected to have related mechanisms of action.

The larger the interaction, the smaller the increase in sample size needed to detect it.

If an interaction is detected, or perhaps only suggested, the comparison of intervention \(X\) would have to be done individually for intervention \(Y\) and its control. However, the power of the comparisons is less than the mariginal total comparisons.

The factorial design has some distinct advantages. If the interaction of two interventions is important to determine, or if there is little chance of interaction, then such a design with appropriate sample size can be very informative and efficient.

However, the added complexity, impact on recruitment and adherence, and potential adverse effects of “polypharmacy” must be considered.

5.7 Group allocation designs#

In group or cluster allocation designs, a group of individuals, a clinic or a community are randomized to a particular intervention or control.

The rationale is that the intervention is most appropriately or more feasibly administered to an entire group. This design may also be better if there is concern about contamination. That is, when what one individual does might readily influence what other participants do.

In group or cluster allocation designs, a group of individuals, a clinic or a community are randomized to a particular intervention or control.

The rationale is that the intervention is most appropriately or more feasibly administered to an entire group. This design may also be better if there is concern about contamination. That is, when what one individual does might readily influence what other participants do.

5.8 Hibrid designs#

Combining historical and randomized controls in a single study.

A number of criteria must be met in order to combine the historical and randomized controls. These include the same entry criteria and evaluation factors and participant recruitment by the same clinic or investigator. The data from the historical

control participants must also be fairly recent.

This approach, if feasible, requires fewer participants to be entered into a trial.

cautions that if biases introduced from the nonrandomized participants (historical controls) are substantial, more participants might have to be randomized to compensate than would be the case in a corresponding fully randomized trial

5.9 Large, simple and paragmatic clinical trials#

The arguments for Large, simple and pragmatic clinical trials:

Advocates of large, simple trials maintain that for common pathological conditions, it is important to uncover even modest benefits of intervention, particularly short term interventions that are easily implemented in a large population.

Sufficiently large number of participants are more important than modest improvements in quality of data. Thus careful characterization of people at entry, or of interim response variables, is unnecessary. And the most important criteria for a valid study are unbiased (i.e. randomized) allocation of participants to intervention or control and unbiased assessment of outcome.

The simplification of the study design and management allows for sufficiently large trials at reasonable cost.

Because of the broad involvement of many practitioners, the results of the trial may be more widely applied than the results of a trial done in just major medical settings.

5.10 Studies of equivalency and non-inferiority#

New interventions may have little or no superiority to existing therapies, but, as long as they are not materially worse, may be of interest because they are less toxic, less invasive, less costly, require fewer doses, improve quality of life, or have some other value to patients.

In studies of equivalency, the objective is to test whether a new intervention is equivalent to an established one. Noninferiority trials test whether the new intervention is no worse than, or at least as good as, some established intervention.

The control or standard treatment must have been shown conclusively to be effective; that is, truly better than placebo or no therapy.

First, the active control that is selected must be one that is an established standard for the indication being studied and not a therapy that is inferior to other known ones.

Second, the studies that demonstrated benefit of the control against either placebo or no treatment must be sufficiently recent such that no important medical advances or other changes have occurred, and in populations similar to those planned for the new trial.

Third, the evidence that demonstrated the benefits of the control must be available so that a control group event rate can be estimated.

Fourth, the response variable used in the new trial must be sensitive to the postulated effects of the control and intervention.

Selecting the margin of indifference or noninferiority, \(d\), is a challenge. Ideally, the relative risk of the new intervention compared to the control should be as close to 1 as possible. For practical reasons, the relative risk is often set in the range of 1.2–1.4. This means that in the worst case, the new intervention may be 20–40% inferior to standard treatment and yet be considered equivalent or noninferior.

The investigator must consider several issues when designing an equivalence or noninferiority trial.

First, the constancy assumption that the control vs. placebo effect has not changed over time is often not correct.

In addition, as background therapy changes, the effect of the control or placebo may also change.

For noninferiority trials, the margin of indifference, \(d\), is specified, where \(I − C < d\). To select the best control \(\rightarrow\) decide the margin of noninferiority \(\rightarrow\) conduct the best trial

5.11 Adaptive designs#

Early phase studies have designs that allow for modifications as the data accrue. Many late phase trials are adaptive in the sense that the protocol allows for modification of the intervention to achieve a certain goal, typically using an interim variable.

Some trials, by design, will adjust the sample size to retain a desired power if the overall event rate is lower than expected, the variability is higher than planned, or adherence is worse than expected. In such cases, the sample size can be recalculated using the updated information

Traditionally, if the effect of the intervention was less than expected, or other factors led to a less than desirable conditional power, the study either continued to the end without providing a clear answer or was stopped early for futility.

A criticism of these designs is that they can introduce bias during the implementation of the adjustment. They may also provide sufficient information to allow people not privy to the accumulating data to make reasonable guesses as to the trend.

Group sequential designs, in common use for many years, are also considered to be response adaptive in that they facilitate early termination of the trial when there is convincing evidence of benefit or harm.

Chapter 6 The Randomization Process#

Randomization tends to produce study groups comparable with respect to known as well as unknown risk factors, removes investigator bias in the allocation of participants, and guarantees that statistical tests will have valid false positive error rates.

Two forms of experimental bias are of concern:

Selection bias, occurs if the allocation process is predictable (i.e. what treatment a participant will get)

Accidental bias, arises when the randomization procedure doesn’t achieve balance on risk factors or prognostic covariates. This is crucial for small studies but for large studies, the chance of accidental bias is negligible.

6.1 Randomization methods#

Fixed allocation randomization#

Fixed allocation procedures assign the interventions to participants with a prespecified probability, usually equal, and that allocation probability is not altered as the study progresses.

Equal or unequal allocation?

An unequal allocation ratio, such as 2:1, of intervention to control. The rationale for such an allocation is that the study may slightly lose sensitivity but may gain more information about participant responses to the new intervention, such as toxicity and side effects.

The rationale for such an allocation is that the study may slightly lose sensitivity but may gain more information about participant responses to the new intervention, such as toxicity and side effects. In some instances, less information may be needed about the control group and, therefore, fewer control participants are required.

Although the loss of sensitivity or power may be less than 5% for allocation ratios approximately between 1/2 and 2/3, equal allocation is the most powerful design and therefore generally recommended.

Simple or complete randomization

A convenient method for producing a randomization schedule is to use a random number producing algorithm, available on most computer systems. A simple randomization procedure might assign participants to group A with probability p and participants to group B with probability 1−p. This procedure can be adapted easily to more than two groups by dividing the interval 0–1 into more than two pieces of length.

The advantage of this simple randomization procedure is that it is easy to implement.

The major disadvantage is that, although in the long run the number of participants in each group will be in the proportion anticipated, at any point in the randomization, including the end, there could be a substantial imbalance (especially when sample size is small). While such imbalances do not cause the statistical tests to be invalid, they do reduce ability to detect true differences between the two groups. In addition, interim analysis of accumulating data might be difficult to interpret with major imbalances in number of participants per arm, especially for smaller trials.

Alternating assignment of participants to the intervention and the control groups (e.g., ABABAB…) is not a form of randomization (except for the first assignment). It’s more vulnerable to unblindness and should be totally avoided.

(Permuted) block randomization

It is used in order to avoid serious imbalance in the number of participants assigned to each group – an imbalance that could occur in the simple randomization procedure.

It guarantees that at no time during randomization will the imbalance be large and that at certain points the number of participants in each group will be equal

If participants are randomly assigned with equal probability to groups A or B, then for each block of even size (e.g., 4, 6, or 8), one half of the participants will be assigned to A and the other half to B. The order in which the interventions are assigned in each block is randomized, and this process is repeated for consecutive blocks of participants until all participants are randomized.

Another method of blocked randomization may also be used. In this method for randomizing the order of assignments within a block of size b, a random number between 0 and 1 for each of the b assignments (half of which are A and the other half B) is obtained.

The advantage of blocking is that balance between the number of participants in each group is guaranteed during the course of randomization. The number in each group will never differ by more than b/2 when b is the length of the block. A second advantage of blocking is that if the trial should be terminated before enrollment is completed, balance will exist in terms of number of participants randomized to each group.

A potential, but solvable problem with basic blocked randomization is that if the blocking factor b is known by the study staff and the study is not double-blind, the assignment for the last person entered in each block is known before entry of that person. This could, of course, permit a bias in the selection of every fourth participant to be entered.

To avoid this problem in the trial that is not double-blind, the blocking factor can be varied as the recruitment continues. In fact, after each block has been completed, the size of the next block could be determined in a random fashion from a few possibilities such as 2, 4, 6, and 8.

A disadvantage of blocked randomization is that, from a strictly theoretical point of view, analysis of the data is more complicated than if simple randomization were used. The data analysis performed at the end of the study should reflect the randomization process actually performed.

Since blocking guarantees balance between the two groups and, therefore, increases the power of a study, blocked randomization with the appropriate analysis is more powerful than not blocking at all or blocking and then ignoring it in the analysis.

Stratified randomization

Investigators may become concerned when prognostic factors are not evenly distributed between intervention and control groups. As indicated previously, randomization tends to produce groups which are, on the average, similar in their entry characteristics, both known and unknown. For any single study, especially a small study, there is no guarantee that all baseline characteristics will be similar in the two groups.

Imbalances in prognostic factors can be dealt with either after the fact by using stratification in the analysis or can be prevented by using stratification in the randomization.

Stratified randomization is a method that helps achieve comparability between the study groups for those factors considered.

Stratified randomization requires that the prognostic factors be measured either before or at the time of randomization. If a single factor is used, it is divided into two or more subgroups or strata (e.g., age 30–34 years, 35–39 years, 40–44 years).

If several factors are used, a stratum is formed by selecting one subgroup from each of them.

The stratified randomization process involves measuring the level of the selected factors for a participant, determining to which stratum she belongs and performing the randomization within that stratum. Within each stratum, the randomization process itself could be simple randomization, but in practice most clinical trials use some blocked randomization strategy.

Blocked randomization is, as described previously, a special kind of stratification.

Small studies are the ones most likely to require stratified randomization, because in large studies, the magnitude of the numbers increases the chance of comparability of the groups.

Increased stratification in small studies can be self-defeating because of the sparseness of data within each stratum. Thus, only important variables should be chosen and the number of strata kept to a minimum.

In addition to making the two study groups appear comparable with regard to specified factors, the power of the study can be increased by taking the stratification into account in the analysis.

Participants in each of the “smaller trials” belong to the same stratum. This reduces variability in group comparisons if the stratification is used in the analysis. Reduction in variability allows a study of a given size to detect smaller group differences in response variables or to detect a specified difference with fewer participants.

It has been argued that there usually does not exist a need to stratify at randomization because stratification at the time of analysis will achieve nearly the same expected power. It appears for a large study that stratification after randomization provides nearly equal efficiency to stratification before randomization. However, for studies of 100 participants or fewer, stratifying the randomization using two or three prognostic factors may achieve greater power although the increase may not be large.

In multicenter trials, centers vary with respect to the type of participants randomized as well as the quality and type of care given to participants during follow-up. Thus, the center may be an important factor related to participant outcome, and the randomization process should be stratified accordingly. Each center then represents, in a sense, a replication of the trial, though the number of participants within a center is not adequate to answer the primary question. Another reason for stratification by center is that if a center should have to leave the study, the balance in prognostic factors in other centers would not be affected.

If in the stratified randomization, a specific proportion or quota is intended for each stratum, the recruitment of eligible participants might not be at the same rate. That is, one stratum might meet the target before the others. If a target proportion is intended, then plans need to be in place to close down recruitment for that stratum, allowing the others to be completed.

Adaptive randomization procedure#

Adaptive procedures change the allocation probabilities as the study progresses

Baseline adpative procedure

The Biased Coin Randomization procedure, originally discussed by Efron, attempts to balance the number of participants in each treatment group based on the previous assignments but does not take participant responses into consideration.

The purpose of the algorithm is basically to randomize the allocation of participants to groups A and B with equal probability as long as the number of participants in each group is equal or nearly equal. If an imbalance occurs and the difference in the number of participants is greater than some prespecified value, the allocation probability (p) is adjusted so that the probability is higher for the group with fewer participants. Efron suggests an allocation probability of p = 2/3 when a correction is indicated.

This approach, from a strictly theoretical point of view, demands a cumbersome data analysis process. The correct analysis requires that the significance level for the test statistic be determined by considering all possible sequences of assignments, which could have been made in repeated experiments using the same biased coin allocation rule where no group differences are assumed to exist.

One possible advantage of the biased coin approach over the blocked randomization scheme is that the investigator cannot determine the next assignment by discovering the blocking factor. However, the biased coin method does not appear to be as widely used as the blocked randomization scheme because of its complexity.

Another similar adaptive randomization method is referred to as the Urn Design, based on the work of Wei and colleagues. From a theoretical point of view, this method, like the biased coin design, would require the analyses to account for the randomization. It seems likely, as for the biased coin design, that if this randomization method is used, but ignored in the analyses, the p-value will be slightly conservative, that is, slightly larger than if the strictly correct analysis were done.

Other stratification methods are adaptive in the sense that intervention assignment probabilities for a participant are a function of the distribution of the prognostic factors for participants already randomized. In general, adaptive stratification methods incorporate several prognostic factors in making an “overall assessment” of the group balance or lack of balance. This method is sometimes called minimization because imbalances in the distribution of prognostic factors are minimized.

Adaptive methods do not have empty or near empty strata because randomization does not take place within a stratum although prognostic factors are used. Minimization gives unbiased estimates of treatment effect and slightly increased power relative to stratified randomization.

The major advantage of this procedure is that it protects against a severe baseline imbalance for important prognostic factors. Overall marginal balance is maintained in the intervention groups with respect to a large number of prognostic factors.

One disadvantage is that adaptive stratification is operationally more difficult to carry out, especially if a large number of factors are considered.

In addition, the population recruited needs to be stable over time, just as for other adaptive methods.

Another disadvantage of adaptive randomization is that the data analysis is complicated, from a strict viewpoint, by the randomization process.

if minimization adaptive stratification is used, an analysis of covariance should be employed.

To obtain the proper significance level, the analysis should incorporate the same prognostic factors used in the randomization.

Minimization and stratification on the same prognostic factors produce similar levels of power, but minimization may add slightly more power if stratification does not include all of the covariates.

Response adaptive procedure

Response adaptive randomization uses information on participant response to intervention during the course of the trial to determine the allocation of the next participant.

Examples of response adaptive randomization models are the Play the Winner and the two-armed bandits models.These models assume that the investigator is randomizing participants to one of two interventions and that the primary response variable can be determined quickly relative to the total length of the study. Both of these response adaptive randomization methods have the intended purpose of maximizing the number of participants on the “superior” intervention. Although these methods do maximize the number of participants on the “superior” intervention, the possible imbalance will almost certainly result in some loss of power and require more participants to be enrolled into the study than would a fixed allocation with equal assignment probability.

A major limitation is that many clinical trials do not have an immediately occurring response variable.

They also may have several response variables of interest with no single outcome easily identified as being the one upon which randomization should be based.

Furthermore, these methods assume that the population from which the participants are drawn is stable over time. If the nature of the study population should change and this is not accounted for in the analysis, the reported significance levels could be biased, perhaps severely. For response adaptive methods, that analysis will be more complicated than it would be with simple randomization. Because of these disadvantages, response adaptive procedures are not commonly used.

Examples of response adaptive randomization models are the Play the Winner and the two-armed bandits models.These models assume that the investigator is randomizing participants to one of two interventions and that the primary response variable can be determined quickly relative to the total length of the study. Both of these response adaptive randomization methods have the intended purpose of maximizing the number of participants on the “superior” intervention. Although these methods do maximize the number of participants on the “superior” intervention, the possible imbalance will almost certainly result in some loss of power and require more participants to be enrolled into the study than would a fixed allocation with equal assignment probability.

A major limitation is that many clinical trials do not have an immediately occurring response variable.

They also may have several response variables of interest with no single outcome easily identified as being the one upon which randomization should be based.

Furthermore, these methods assume that the population from which the participants are drawn is stable over time. If the nature of the study population should change and this is not accounted for in the analysis, the reported significance levels could be biased, perhaps severely. For response adaptive methods, that analysis will be more complicated than it would be with simple randomization. Because of these disadvantages, response adaptive procedures are not commonly used.

Final notes#

The manner in which the chosen randomization method is actually implemented is very important. If this aspect of randomization does not receive careful attention, the entire randomization process can easily be compromised, thus voiding any of the advantages for using it.

In some cases, the clinic may register a participant by dialing into a central computer and entering data via touchtone, with a voice response. These systems, referred to as Interactive Voice Response Systems or IVRS, or Interactive Web Response Systems, IWRS, are effective and can be used to not only assign intervention but can also capture basic eligibility data.

For large studies involving more than several hundred participants, the randomization should be blocked.

If a large multicenter trial is being conducted, randomization should be stratified by center.

Randomization stratified on the basis of other factors in large studies is usually not necessary, because randomization tends to make the study groups quite comparable for all risk factors.

For small studies, the randomization should also be blocked and stratified by center if more than one center is involved.

Since the sample size is small, a few strata for important risk factors may be defined to assure that balance will be

achieved for at least those factors.

For a larger number of prognostic factors, the adaptive stratification techniques should be considered and the appropriate analyses performed. As in large studies, stratified analysis can be performed even if stratified randomization was not done.

Chapter 7 Blindness#

Bias may be defined as systematic error, or “difference between the true value and that actually obtained due to all causes other than sampling variability”

Large sample size does not reduce bias although it generally improves precision and thus power.

A clinical trial should, ideally, have a double-blind design in order to avoid potential problems of bias during data collection and assessment. In studies where such a design is impossible, other measures to reduce potential bias are advocated.

Types of trials (in terms of blindness)#

An unblinded study is appealing for two reasons. First, all other things being equal, it is simpler to execute than other studies.

Second, investigators are likely to be more comfortable making decisions, such as whether or not to continue a participant on his assigned study medication if they know its identity.

The main disadvantage of an unblinded trial is the possibility of bias.

In a single-blind study, only the investigator is aware of which intervention each par- ticipant is receiving.

Both unblinded and single-blind trials are vulnerable to another source of potential bias introduced by the investigators. This relates to group differences in compensatory and concomitant treatment. (This may be in the form of advice or therapy.)

In a double-blind study, neither the participants nor the investigators responsible for following the participants, collecting data, and assessing outcomes should know the identity of the intervention assignment.

The main advantage of a truly double-blind study is that the risk of bias is reduced.

The double-blind design is no protection against imbalances in use of concomi- tant medications.

A triple-blind study is an extension of the double-blind design; the committee monitoring response variables is not told the identity of the groups.

However, in a trial where the monitoring committee has an ethical responsibility to ensure participant safety, such a design may be counterproductive.

A triple-blind study can be conducted ethically if the monitoring committee asks itself at each meeting whether the direction of observed trends matters. If it does not matter, then the triple-blind can be maintained, at least for the time being.

Protecting the double-blind design#

One of the surest ways to unblind a drug study is to have dissimilar appearing medications.

When the treatment identity of one participant becomes known to the investigator, the whole trial is unblinded. Thus, matching of drugs is essential.

Cross-over studies, where each subject sees both medications, require the most care in matching.

Drug preparations should be pretested if it is possible. One method is to have a panel of observers unconnected with the study compare samples of the medica- tions.

It is usually prudent to avoid using extra substances unless absolutely essential to prevent unblinding of the study.

In addition, enclosing tablets in capsules may change the rate of absorption and the time to treatment response.

As long as each active agent is not being compared against another, but only against placebo, one option is to create a placebo for each active drug or a so-called “double-dummy.”

By drug coding is meant the labeling of individual drug bottles or vials so that the identity of the drug is not disclosed.

One side effect in one participant may not be attributable to the drug, but a constellation of several side effects in several participants with the same drug code may easily unblind the whole study.

This type of coding has no operational limits on the number of unique codes; it simplifies keeping an accurate and current inventory of all study medications and helps assure that each participant is dispensed his assigned study medication.

A procedure should be developed to break the blind quickly for any individual participant at any time should it be in his best interest.

Known pharmaceutical effects of the study medication may lead to unblinding.

Another way of estimating the success of a double-blind design is to monitor specific intermediate effects of the study medication.

Assessing and reporting of blindness#

Randomized trials with inadequate blinding, on average, show larger treatment effects than properly blinded trials

In assessing the success of blindness, decisions have to be made when to conduct the assessment and what questions to ask.

We believe that monitoring and reporting of the success of blindness are important for two reasons. First, knowing that the level of this success is one of the measures of trial quality may keep the investigators’ attention on blindness during trial conduct. Second, it helps readers of the trial report determine how much confidence they can place on the trial results.

Chapter 8 Sample size/power calculation#

Chapter 11 Data collection and quality control#

Chapter 12 Assessing and reporting adverse events#

Chapter 16 Monitoring response variables#

16.1 Monitoring committee#

16.2 Statistical methods used in monitoring (interim analysis)#

Classical sequential methods#

Group sequential methods#

Flexible group sequential procedures: alpha spending functions#

Asymmetric boundaries#

Curtailed sampling and conditional power procedures#

Other approaches#

Chapter 17 Issues in data analysis#

Analysis populations#

Missing data or poor quality data#

Competing events#

Composite outcomes#

Covariate adjustment#

Subgroup analyses#

Comparison of multiple variables#

Use of cutpoints#

Analysis of non-inferiority trial#

Analysis following trend adaptive designs#

Meta-analysis of multiple studies#

Chapter 18 Closeout#

Chapter 19 Reporting and interpreting of results#

Lawrence M Friedman, Curt D Furberg, David L DeMets, David M Reboussin, and Christopher B Granger. Fundamentals of clinical trials. Springer, 2015.