Correlated/Longitudinal Data Analysis

Based on course notes and blog posts

Cross-sectional vs longitudinal data

-

Cross-sectional (CS) study can be reduced from the longitudinal study (LS) if the number of measures per subject is equal to one, ie $n_i=1$.

$$ Y_{i1}=\beta_cx_{i1}+\varepsilon_{i1}, i=1,\cdots, m $$- $\beta_c$ represents the difference in average $Y$ across two sub-populations which differ by one unit in $x$.

-

With repeated measures, above model becomes LDA model:

$$ Y_{ij}=\beta_cx_{i1}+\beta_L(x_{ij}-x_{i1})+\varepsilon_{ij}, i=1,\cdots,m; j=1,\cdots,n_i $$-

Notice that $\beta_L$ represents the expected change in $Y$ over time per one unit change in $x$, w.r.t its baseline value: $$(Y_{ij}-Y_{i1})=\beta_L(x_{ij}-x_{i1})+\varepsilon_{ij}-\varepsilon_{i1}$$

-

When $n=1$, above two models are identical.

-

It's more common that $\beta_C$ and $\beta_L$ have the same sign. However, it may exist that they have opposite sign.

-

In CS the basis is a comparison of individuals with a particular value of $x$ to others with a different value

-

In LDA each person is his/her own control. $\beta_L$ is estimated by comparing a person's response at two times assuming that $x$ changes over time.

-

Estimation of $\beta_C$ is confouned by unmeasured individual characteristic; while estimation of $\beta_L$ is less likely to be affected by unmeasured confounding. (since, if the confounders are not time-varing, they will be cancelled out when doing model (2)-(1)).

-

Graphic representation of longitudinal data

Y against Time

- Check the time trend for every individual

- Check the variability change over time (esp. at beginning vs end)

Instead of using $Y$, use the standardized residuals:

$$ y_{iJ}^*= \frac{y_{iJ}-\bar{y}_{\cdot J}}{s_J} $$$$ \bar{y}_{\cdot J}= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^ny_{iJ}, s_J^2= \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n(y_{iJ}- \bar{y}_{ \cdot J})^2 $$- Spaghetti plot

- ZAP plot: using residuals

- regress $y_{ij}$ on $t_{ij}$ and get the residuals $r_{ij}$

- choose on dimensional summary of the residuals, for example $g_i=\text{median}(r_{i1},\cdots, r_{in_i})$

- plot $r_{ij}$ vs $t_{ij}$ using points (quantiles of $g_i$)

- order units by $g_i$ (min, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, max)

- add lines for selected quantiles of $g_i$

Y against X

-

AV plot

-

Graphic methods to separate CS information from LS information

The model

$$ y_{ij}= \beta_Cx_{i1}+ \beta_L(x_{ij}-x_{i1})+ \varepsilon_{ij}, i=1, \cdot,m; j=1, \cdots,n $$suggests making two scatterplots:

i. $y_{i1}$ Against $x_{i1}$ for $i = 1, \cdots, m$

ii. $y_{ij} - y_{i1}$ against $x_{ij} - x_{i1}$ for $i = 1, \cdots, m; j = 2, \cdots, n$

From the plots, we can then ask:

i. are the differences acros subjects? (CS effect)

ii. are there changes across time within subjects? (LS effect)

Fitting smooth curves

$$ Y_i= \mu(t_i)+ \varepsilon_i, i=1, \cdots,m $$We want to estimate an unknown mean response curve $\mu(t)$ in the model. Nonparametric regression models that can be used to estimate the mean response profile as a function of time.

Alawys, the smaller of the window width the less smoothness we get.

Kernel estimation

-

selection of window centered at time $t$;

-

$\hat{\mu}(t)$ is the average of $Y$ of all points that are visible in that window

-

slide a window from the extreme left to extreme right, calculating $\hat{ \mu}(t_i)$ for each

-

a "better" method is to use a weight function that changes smoothly with time and gives weights to the observations closer to $t$. E.g. Gaussian kernel $K(t_i)=\exp(-0.5t_i^2)$ (i.e. $N(0,1))$

-

at window with $t=t_1$,

$$ \hat{ \mu}(t_1)= \sum_{i=1}^m \omega(t_1,t_i,h)y_i/ \sum_{i=1}^m \omega(t_1,t_i,h) $$Where $h$ controls the smoothness.

Smoothing spline

-

Smoothing spline (cubic): the function $s(t)$ that minimizes the criterion

$$ J( \lambda)= \sum_{i=1}^m \{y_i-s(t_i) \}^2+ \lambda \int s''(t)^2dt $$ -

$s(t)$ Satisfies the criterion if and only if it is a piecewise cubic polynomial

-

$\lambda$ Smaller $\Rightarrow$ curve less smooth

-

$\int s''(t)^2dt$: roughness penalty

Loess

- Center a window at time $t_i$

- fit weighted least squares

- Calculate the residuals

- Down weight the outliers and repeat 1, 2, 3 many times

- the result is a fitted line that is insensitive to the observations with outlying $Y$ values

Exploring correlation structure

-

Let $y_{ij}=\beta_0+x_{ij}\beta+\varepsilon_{ij}$, we should be clear that

$$ cor(y_{ij},y_{ik}) \ne cor( \varepsilon_{ij}, \varepsilon_{ik})=cor(y_{ij},y_{ik}|x_{ij},x_{ik}) $$similarly, $var(y) \ne var(\varepsilon)$.

-

We explore the correlation structure based on the residuals of the model. And it is used for equally spaced data, not for irregular data.

-

Weakly stationary: if residuals have constant mean and variance and if $corr(y_{ij}, y_{ik})$ depends only on $|t_{ij}- t_{ik}|$, then the process $Y_{ij}$ is said to be weakly stationary.

-

Autocorrelation function (ACF)

$$ \rho(u)=corr(Y_{ij},Y_{ij-u}) $$for all $i$, which is pooling observation pairs along the diagonals of the scatter plot matrix.

$$ se( \rho(u)) \approx 1/ \sqrt{N} $$Where $N$ is the number of independent pairs in the calculation.

-

ACF is most effective for studying equally spaced data that are roughly

stationary.

-

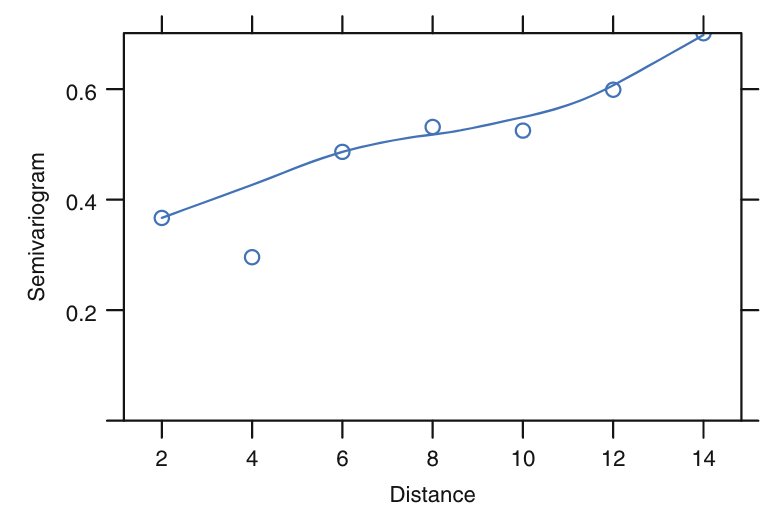

For irreguarly-sapced data, we can use Variogram:

- the time difference between all possible pairs of measurements on the same subject is played against the covariance of the pair of measurements within subjec

-

If $Y(t)$ is stationary, the Variogram is directly related to the ACF $\rho(u)$ by

$$ \gamma(u)= \sigma^2 \{1- \rho(u) \} $$Where $\sigma^2$ is the variance of $Y$:

$$ \begin{align*} E(X-Y)^2 &= [E(X-Y)]^2+Var(X-Y)\\ &= 0+Var(X)+Var(Y)-2Cov(X,Y)\\ &= 2\sigma^2-2\rho\sigma^2\\ &= \sigma^2(1-\rho) \end{align*} $$ -

Calculating $\gamma(u)$, the Vriagram:

-

Starging with the residulas $r_{ij}$ and the time $t_{ij}$, compute all possible

$$ v_{ijk}= \frac{1}{2}(r_{ij}-r_{ik})^2 $$and

$$ u_{ijk}=t_{ij}-t_{ik} \text{ for } jSmooth $v_{ijk}$ against $u_{ijk}$ (using lowess)

Estimate the total variance as

$$ \hat{ \sigma}^2= \frac{1}{N-1} \sum_{ij}(r_{ij}- \bar{r})^2 $$If the time $t_{ij}$ are not total irregular, i.e. there will be more than one observations at each vlaue of $u$. Then let

$$ \hat{ \gamma}(u)= \frac{ \sum_{i=1}^{n_i}v_{ijk}}{n_i} $$

-

Fig. 7.3 of [1]

Linear model for correlated data (continuous outcome)

excerpt from Chapter 7 of [1:1]

-

To develop a general linear model framework for longitudinal data, in which the inference we make about the parameters of interest ($\beta$) recoginze the likely correlation structure of the data. There are two ways to archieve this:

Random effects model (conditional model)

$$ Y_{ij} = U_i + \beta_0 + \beta_1t_j + \epsilon_{ij} $$Where

$$ U_i \sim N(0, v^2), \text{variantion between units/clusters} $$$$ \epsilon_{ij} \sim N(0, \tau^2), \text{variantion within units } $$ $\rho = \frac{v^2}{v^2 + \tau^2}$, proportion of total variance due to between-unit variation

-

$var(y_{ij}|U_i) = \tau^2, cov(y_{ij}, y_{ij'}|U_i)=0$

-

Example: random effects (repeated measures) ANOVA:

-

we can treat the group (condition) variable as the orignial “time” variable, i.e. the repeated meaures are observed on different conditions (which cause the groups effect that we are interested in).

$$ y_{ij} = \mu_j + U_i + \epsilon_{ij} $$where

$$ \mu_j, j=1, \cdots, n \text{ is the group effects} $$$$ U_i \sim N(0, v^2) \text{ is the between subjects random effects} $$$$ \epsilon_{ij} \sim N(0, \tau^2) \text{ is the random error} $$ -

Total sum of squares = between group sum of squares + within group sum of squares

-

-

Heteogeneity: variation between groups implies (relative) similarity/correlation within groups. If $v^2 >> \tau^2 \Rightarrow \rho \rightarrow 1 \Rightarrow$ significant difference between groups.

MMRM

-

MMRM (mixed model of repeated measures) is a special case of linear mixed model (LMM)[4]

- it doesn’t specify any random effects but it specifies a correlated residual error structure. (similar as the GLS or marginal model?)

-

MMRM vs LMM

- The first thing to remember is that it generally only makes sense to fit the MMRM if subjects are measured at a common set of times.

- If the measurements occur on a more ad-hoc basis, such that the times of measurement vary across subjects, what is typically called the MMRM model can’t really be fitted.

- It is worth noting that in this case, if one uses a relatively simple random effects structure (e.g. intercepts and slopes) one can still specify that the residual errors are serially correlated over time. Here the correlation in errors is accommodating residual correlation between measurements close in time that cannot be captured by the simple random effects structure. See Section 3.3.4 of [5] for more on this.

-

If the correlation structure of the repeated measures implied by the specified random effects is incorrect, the standard errors may be general biased. This potential issue suggests that in this setting the the MMRM, which uses an unstructured covariance structure for the residual errors, is preferable.

-

With missing values, mixed models fitted by maximum likelihood are obtained under the missing at random assumption.

-

If the number of measurement times is moderate or large and there are missing values, sometimes one can encounter convergence problems with the unstructured covariance matrix in the MMRM. In the case of this occurring, trials often pre-specify to use models which parametrise the residual error covariance matrix using fewer parameters (e.g. first order autoregressive).

- A possible alternative would be use doubly robust estimation, which would be (asymptotically) unbiased if either the outcome model (including the simpler parametrisation for the residual covariance matrix) or the model for dropout (missingness) were correct.

-

SAS warning in MMRM model (or proc mixed macro) and how to handle it

- Example warning message:

The Hessian (or G or D) Matrix is not positive definite. Convergence has stopped.

- Meaning of the warning:

- The Hessian Matrix is based on the D Matrix (the variance covariance matrix of the random effects), and is used to compute the standard errors of the covariance parameters.

- Algorithms that estimate these parameters get stuck if the Hessian Matrix doesn’t have those same positive diagonal entries.

- What to do about it?

- To check the scaling of your predictor variables. Variables with vastly different scales may lead to this issue

- To respecify the random parts of the model: reduce number of random effects, specify a different covariance structure (usually simpler structure)

- Change to a different model, such as GEE model

- Reference

- Example warning message:

Marginal model (population average)

-

Generalized least squares is based on these ideas, and can incorporate multiple types of correlation structures without including any random effects.[6]

-

Generalized least squares, Markov models when no random effects are added, and GEE are all examples of marginal models, marginal meaning in the sense of not being conditional on subject so not attempting to estimate individual subjects’ trajectories.

-

With exchangable (or CS) variance-covariance structure (balanced data)

$$ Y_{ij} = \beta_0+\beta_1t_j+\epsilon_{ij}, i=1, \cdots, m; j=1, \cdots, n\\ Cov(Y_i) = \sigma^2V_0\\ $$where

$$ V_0 = \rho J+(1-\rho)I\\ \rho=corr(y_{ij}, y_{ij'}), \text{ for $j \ne j'$} $$- Marginal model with CS variance structure is equivalent with random effects (intercept) model: the same $E(Y_i)$ and $Cov(Y_i)$ structures, thus wil return the same estimate of the parameters.

-

Exponential correlation/autoregressive model

-

Correlation b/t a pair of measurements of the same subject decays towards 0 as the time separation b/t the measurement increases, i.e.

-

For unequally-spaced data

$$ cov(y_{ij}, y_{ik}) = (V_0)_{ij} = v_ij = \sigma^2e^{-\phi|t_j-t_k|} $$ -

For equally-spaced data

$$ t_{j-1}-t_j = d $$For all $j$, then $v_{jk}=\sigma^2\rho$, where $\rho=\exp(-\phi d)$ is the correlation b/t successive observations on the same subject.

-

-

In marginal model, we model the mean and the covariance strucutre separately:

$$ E(Y_i) = \mu = X_i\beta\\ Cov(Y_i) = CS/AR(1)/... $$ -

Three basic elements of correlation structures:

- Random effects

- Autocorrelation or serial dependence

- Noise, measurements error

-

Modelling the correlation in longitudinal data is important to be able to obtain correct inference on $\beta$s. Incorporating correlation into estimation of regression models is achieved via weighted least squares.

-

Weighted least-squares (WLS) estimation

All following etimators are weighted LS etimators, the difference is in the choince of the weight and its impact on the variance (or efficiency thus the interval) estimation of beta.

Generalized least squares is like weighted least squares but uses a covariance matrix that is not diagonal.

- (no distribution assumption on $y$) The weighted least-squares estimator of $\beta$, using a symmetric weight matrix, $W$, is the value $\hat{\beta}_W$, which minimize the quadratic form

-

Standard matrix manipulations give the explicit result

$$ \hat{\beta}_W = (X'WX)^{-1}X'Wy $$-

It's an unbiased estimator of $\beta$, whatever the choice of $W$.

-

$\text{Var}(\hat{\beta}_W) = \sigma^2\{(X'WX)^{-1}X'W\}V\{WX(X'WX)^{-1}\}$

-

When $W = I$, it reduces to the OLS estimator $\hat{\beta}_I = (X'X)^{-1}X'y$, with $\text{Var}(\hat{\beta}_I) = \sigma^2(X'X)^{-1}X'VX(X'X)^{-1}$

-

When $W = V^{-1}$, the estimator becomes the MLE (under the assumption of normal distribution): $\hat{\beta} = (X'V^{-1}X)^{-1}X'V^{-1}y$ with $\text{Var}(\hat{\beta}) = \sigma^2(X'V^{-1}X)^{-1}$

-

-

According to the Gauss-Markov theorem, the MLE is the most efficient linear estimator for $\beta$. However, to identify this optimal weighting matrix we need to know the complete correlation structure of the data - we don't need to know $\sigma^2$, because $\hat{\beta}_W$ is unchanged by proportional changes in all the elements of $W$.

-

Also, because the correlation structure may be difficult to identify in practice, it is of interest to ask how much loss of efficiency might result from using a different $W$

-

When we know the correlation structure is CS (uniform/exchangable), the OLS is fully efficient as the WLS estimator; an intuitive explanation is that with a common correlation b/t any two equally spaced measurements on the same unit, there is no reason to weight measurements differently.

Using OLS estimator is misleading when V $\ne$ I

-

In many circumstances where there is balanced design, the OLS estimator, $\tilde{\beta}$, is perfectly satisfactory for point estimation. But this is not always the case. (Example in book page 63)

-

Even when OLS is reasonably efficient, it is clear from the form of its variance

$$ \text{Var}(\tilde{\beta}) =\sigma^2(X'X)^{-1}X'VX(X'X)^{-1} $$That interval estimation for $\beta$ still requires information about $\sigma^2 V$, the variance matrix of the data. In particular, the usual formula for the variance of the least-squares estimator,

$$ \text{Var}(\tilde{\beta}) = \sigma^2(X'X)^{-1} $$Assumes that $V = I$, the identify matrix, and can be seriously misleading when it is not so.

-

A naive use of OLS would be to ignore the correlation structure in the data and to base interval estimation for $\beta$ on the variance above with $\sigma^2$ being replaced with its usual estimator, the residual mean square

$$ \tilde{\sigma}^2 = (nm - p)^{-1}(y-X\tilde{\beta})'(y-X\tilde{\beta}) $$There are two sources of error in this native approach when $V \ne I$:

- $\text{Var}(\tilde{\beta})$ is wrong

- $\tilde{\sigma}^2$ is no longer an unbiased estimator of $\sigma^2$

MLE under Gaussian assumptions

-

Simultaneous estimtation of the parameter of interest $\beta$ and of covariance parameters $\sigma^2$ and $V_0$ using the likelihood function (profile likelihood method)

-

The log-likelihood function for observed data $y$ is

$$ L(\beta, \sigma^2, V_0) = -0.5\{nm\log(\sigma^2) + m\log(|V_0|) + \sigma^{-2}(y-X\beta)'V_0^{-1}(y-X\beta)\} $$-

By fixing $V_0$ and $\sigma^2$ first, we calculate

$$ \hat{\beta}(V) = (X'V^{-1}X)^{-1}X'V^{-1}y $$ -

Maximize $L(\hat{\beta(V), \sigma^2, V_0})$ w.r.t. $\sigma^2$ and get

$$ \hat{\sigma}^2(V_0) = RSS(V_0)/nm $$where $RSS(V_0) = (y - X\hat{\beta}(V_0))'V^{-1}(y - X\hat{\beta}(V_0))$

-

Then maximize the updated likelihood w.r.t. $V_0$ and get $\hat{V}_0$

-

-

By using the profile likelihood method, we gain computational advantage (since we reduce the number of parameters to be maximized in one iteration) since there are closed forms for the MLEs.

REML

-

To improve the estimation of the $\sigma^2$ from MLE, which is biased, to get an unbiased estimator based on the linearly transformed set of data $\bf{Y}^* = \bf{AY}$ such that the distribution of $\bf{Y}^*$ doesn't depend on $\beta$

-

We call the likelihood for the transformed data $\bf{Y}^*$ marginal likelihood for $\sigma^2$ and $V_0$ since it doesn't contain $\beta$ parameters

-

We choose the transforming matrix $\bf{A}$ as

$$ \bf{A = I - X(X'X)^{-1}X'} $$However, this matrix is singular. To obtain a non-singular distribution, we can use only $N-p$ rows of the $\bf{A}$ matrix. Actually, the estimators for $\sigma^2$ and $V$ do not depend on which rows we use, nor on the particular choice of $\bf{A}$: any full-rank matrix with the property that $E(\bf{Y}^*) = 0$ for all $\beta$ will give the same answer.

Robust estimation (unstructured covarince matrix)

-

Not willing to specify a parameteric model for the covariance structure $V$ for $\bf{Y}$, a "robust" estimation of $\beta$ resembles the form of a WLS estimator by using the working covariance matrix (weight) $W$:

$$ \tilde{\beta}_W = (X'WX)^{-1}X'Wy $$and the variance of $\tilde{\beta}_W$ takes a sandwich form:

$$ \hat{R}_W = \{(X'WX)^{-1}X'W\}\hat{V}\{(X'WX)^{-1}X'W\} $$where $\hat{V}$ is a consistent estimate for $V$ whatever the true covariance structure is.

-

Robust estimation of $V$

-

Data: $\{y_{hij}\}, h = 1, \cdots, g; i = 1, \cdots, m_h; j = 1, \cdots, n$, where $h$ = treatment, $i=$ subject, and $j=$ time point.

-

Let $E(Y_{hij}) = \mu_{hj}, h = 1, \cdots, g; j = 1, \cdots, n.$ A saturated model for the covariance matrix assumes

$$ \text{Var}(Y) = V, $$With non-zero diagnola blocks equal to $V_0$, a positive definite but otherwise arbitrary $n \times n$ matrix.

-

The REML estimator for $V_0$ is:

$$ \hat{V}_0 = (\sum_{h=1}^g m_h - g)^{-1}\times\sum_{h=1}^g\sum_{i=1}^{m_h}(y_{hi}-\hat{{\bf\mu}}_h)(y_{hi}- \hat{{\bf\mu}}_{h})' $$where

$$ {\bf y}_{hi} = (y_{hi1}, \cdots, y_{hin})'\\ {\bf\mu}_h = (\mu_{h1}, \cdots, \mu_{hn})'\\ \hat{\mu}_{hj} = \frac{1}{m_h}\sum_{i=1}^{m_h}y_{hij}, j = 1, \cdots, n $$

-

-

The MLE of $V$: when the saturated model strategy is not feasible, typically when data are from observational studies with continuous covariates, we can estimate $V$ by maximizaing the likelihood - however this approach depends on how $V$ is.

-

For unlalanced data, $V$ is still block diagonal, but the $V_{0i}$ will have different sizes. We can estimate $V_{0i}$ as

$$ \hat{V}_{0i} = ({\bf y}_i - \hat{\bf \mu}_i)({\bf y}_i - \hat{\bf \mu}_i)', $$Where $\hat{\bf \mu}_i$ is the OLS estimate of ${\bf \mu}_i$ from the most complicated model we are prepared to entertain for the mean response.

-

The steps can be summarized as follows

-

Specify saturated model for the mean

$$ E(Y_{hij}) = \mu_{hij} $$ -

Estimate $\mu_{hj}$ by OLS and get $\hat{\mu}_{hj}$

-

REML estimate of $\hat{V}_0$

-

By using $\hat{V}_0$, we get robust s.e. estimate for $\beta$

-

-

Robust estimation v.s. parametric approach

-

The crucial difference b/t these two methods is that, with robust estimation, a poor choice of $W$ will affect only the efficiency of the inference for $\beta$, not the validity.

-

CI and hypothesis tests are derived from

$$ \tilde{\beta}_W \sim MVN(\beta, \hat{R}_W) $$which will be asymptotically correct whatever. the true form of $V$.

-

We can get consistent estimate of $V$ by REML under a saturated model.

-

-

Comparison

- Efficiency: optimal weighted least-squares estimate uses a weight matrix whose inverse is proportional to the true covariance matrix so it would seem reasonable to use the data to estimate this optimal weight matrix.

- The robust estimation also requires to estimate the V matrix using the data, however it always involves more parameters (total $n(n + 1)/2$ in unstructured) than the covariance matrix under parametric assumption.

- So the robust approach is usually satisfactory when the data consist of short, complete sequence of measurements observed at a common set of times on many experimental units, and care is taken in the choice of the working correlation matrix. In other circumstance, it is worth considering a parametric modeling approach.

Transition/stochastic/Markov model

- Markov models (see especially here and here for references) are more general ways to incorporate a variety of correlation structures with or without random effects.

- Markov models are more general because they easily extend to binary, nominal, ordinal, and continuous outcome. They are computationally fast and require only standard frequentist or Bayesian software until one gets to the post-model-fit stage of turning transition probabilities into state occupancy probabilities.

Generalized linear models (GLM) for longitudinal data

graph TD

a[GLM for longitudinal data] --> b[Continuous outcome: identity link]

a --> c[Discrete outcome: logit/log link]

b --> d["Is var(Yi) known?"]

d -- Yes --> e[WLS]

d -- No --> f["model var(Yi) in addition to E(Yi|Xi)?"]

f -- Yes --> g[marginal model]

g --> g1[MLE]

g --> g2[RMLE]

f -- No --> h[Robust estimation]

c --> i[Marginal mdoel]

c --> j[Trasitional model]

c --> k[random effects model]

i --> i1[GEE: quasi-likelihood]

j --> l[Likelihood based]

k --> l

b --> i1

- G(eneralized) is used for non-normal outcoes

- GEE is used for correlated data, and for both continuous and discrete outcomes; when used in continuous outcome, it is equivalent to LMM (linear mixed model)

- GEE and GLMM (generalized linear mixed model) are not equivalent as $E(g(x))\ne g(E(x))$, where $g(\cdot)$ is a non-linear function (or transformation).

Continuous outcome

- When we don't know the true variance-covariance structure of $\bf{Y}_i$, we mainly have to options: impose paramatric assumption of the covariance structure or leave it unspecied (robust method).

- Essentially, the estimate of $\beta$ has the form of weighted least squares no matter which method we use, and it's valid. The dierence lies on $\text{var}(\beta)$, depending on the different weights that are assumed.

Parametric method

-

Parametric model on $\text{var}(Y_i)$. The model is then fully specied: first two moments and distribution, then we can use ML or REML method to find the MLE of the parameters and make inference on them.

-

The advantage on of REML over ML is that, the ML estimates of the variance components, $\sigma^2$ the diagnoal part, is biased. Using REML can avoid this and get unbiased estimates.

-

The MLE of $\sigma^2$, $\hat{\sigma}^2 = RSS/(nm)$, where $RSS$ is the residual sum of squares and $nm$ is the number of observations in total. While the RMLE of $\sigma^2$ is $\tilde{\sigma}^2 = RSS/(nm-p)$, where $p$ is the number of elements in $\beta$.

-

For ${\bf Y} \sim MVN(X\beta, \sigma^2V)$, the MLEs are found by using profile likelihood technique:

$$ \hat{V}_0 = \arg\max L_r(V_0)\\ \hat{\beta} = \hat{\beta}(\hat{V}_0)\\ \hat{\sigma}^2 = \hat{\sigma}^2(\hat{V}_0) $$ -

Note that $V_0$ has effect on $\hat{\beta}$ for its variance but not expectation.

Robust method

-

Without assuming the parametric form of $\text{var}({\bf Y}_i)$, we may select a "working" covariance matrix as the weight, say $W$. Then the robust estimate of $\beta$ is given by

$$ \tilde{\beta}_W = (X'WX)^{-1}X'Wy $$With variance

$$ \hat{R}_W = \{(X'WX)^{-1}X'W\}\hat{V}\{(X'WX)^{-1}X'W\} $$Where $\hat{V}$ is a consistent estimate of $V$ whatever the true covariance structure is.

Discrete outcome

Marginal model (using GEE)

Why GEE

- We can not easily generalize the rules used in continuous type outcome to discrete outcome, since there is no ready to use multivariate version of discrete distributions corresponding to the univariate ones (binomial/Poisson)

- Simplicity: formulating quasi-score equation only needs to specify the first two moments of the outcomes; the variance is always a function of the mean of the outcome

- Consistency: despite the miss specification fo the covariance structure, the estimate of the regression coefficient is still valid. The specification of variance only affect the efficiency of the estimated coefficient, if the variance structure is correctly specified, the estimate is MLE and most efficient.

Details of GEE

-

GEE function:

$$ U(\beta) = \sum_{i}\frac{\partial \mu_i'(\beta)}{\partial\beta}V_i({\bf y_i - \mu_i(\beta)}) $$ -

Estimate of $\beta$

$$ \hat{\beta} = (\sum_iD_i'V_i^{-1}D_i)^{-1}D_i'V_i^{-1}y_i, $$Where $D_i = \frac{\partial \mu_i(\beta)}{\partial \beta}$.

$$ \text{Cov}(\hat\beta) = \left(\sum_iD_i'V_i^{-1}D_i\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_iD_i'V_i^{-1}\text{var}(y_i)V_i^{-1}D_i\right)\left(\sum_iD_i'V_i^{-1}D_i\right)^{-1} $$the robust version.

Comments on GEE

-

GEE is the maximum likelihood score equation for multivariate Gaussian data, and for binary data when $\text{var}(Y_i)$ is correclty specified.

-

$\hat{\beta}$ is consistent when sample size goes to infinity even when $\text{var}(Y_i)$ is incorrectly specified

-

Disadvantages of GEE

- it is a large sample approximate method;

- it does not use a full likelihood function so cannot be used in a Bayesian context;

- not being full likelihood the repeated observations are not properly “connected” to each other, so dropouts and missed visits must be missing completely at random, not just missing at random as full likelihood methods require.

Appendix: Limitation of OLS models in analyzing repeated measures data

Date: Feb 28, 2014

-

One of the most important assumptions for appropriate F-tests when using OLS in repeated measures data is that there is a constant correlation among multiple measure- ments within a subject.

-

Some authors have suggested the use of repeated measures MANOVA instead of univariate repeated measures ANOVA when the assumption of constant covari- ance is not met. This is a reasonable approach if there are no missing data. But MANOVA requires that the data for all indi- viduals be available for exactly the same time points to estimate the covariance matrix.

-

Algorithms for the computation of variance components using OLS are not optimal when data are missing, even if the assumptions about the covariance structure are correct

-

linear mixed models, which uses an estimation algorithm called generalized least squares (GLS) is designed to deal with correlated data.

-

Basically, GLS estimates are appropriately weighted based on the covariance structure of the data. The estimates of the variance components are acquired by maximizing either the full likelihood (maximum likelihood, or ML) or a restricted version of the likelihood (restricted or residual maximum likelihood, or REML).

-

growth curves test for differences in initial values and in rates of growth of each factor’s levels, allowing for a more straightforward interpretation of data. A particular implementation of the growth curve model is called the random coefficients growth curve, where each subject’s parameters are considered a random draw from a population of such parameters. This implementation is also known as multilevel models, or hierarchical linear models.

-

The mixed model, although slightly more complicated than the other two structures (requiring the estimation of four rather than two variance components), it is appealing because it is so broadly applicable. We also had some indication from previous work that this structure might be less sensitive to misspecification, and thus more robust in our analyses.

-

The determinat of the variance/covariance matrices is a indicator of the variability of the model account for the data.

-

Independent random errors can be manipulated to assume any covariance structure by premultiplying the independent variates by some square-root decomposition of the covariance structure. (eg [Cholesky decomposition] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cholesky_decomposition))

-

The repeated measures OLS algorithm produces accurate F-tests when data are balanced, and quite reasonable results when data are unbalanced and the variance/covariance structure of the data is CS.

References

Harrell, Frank E and others (2015). Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. ↩︎ ↩︎

the convariance structure is usually the nuiance parameter ↩︎

Two categories of robustness: 1. w.r.t. the outlier; 2. w.r.t. the model assumptions ↩︎

1.MMRM vs LME model, 2.Mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) in Stata, SAS and R ↩︎

Verbeke, Geert (1997). Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. ↩︎

Longitudinal Data: Think Serial Correlation First, Random Effects Second ↩︎