Meta-analysis

Basic introduction to fixed- vs random-effects meta-analysis model [1]

[Earlier notes](./attachments/A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis.pdf)

- There are two popular statistical models for meta-analysis, the fixed-effect model and the random-effects model.

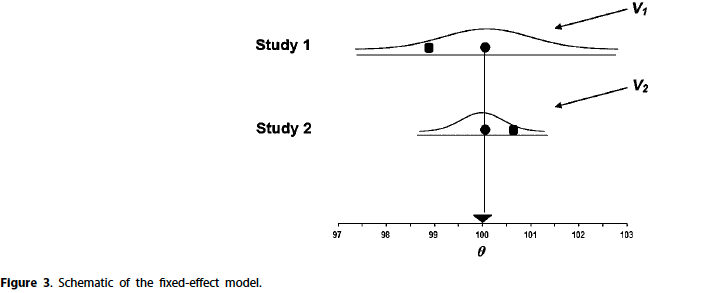

- Under the fixed-effect model we assume that there is one true effect size that underlies all the studies in the analysis, and that all differences in observed effects are due to sampling error.

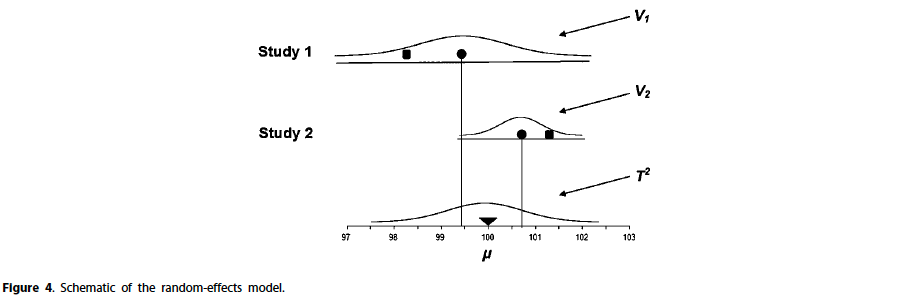

- By contrast, under the random-effects model we allow the true effect sizes to differ—it is possible that all studies share a common effect size, but it is also possible that the effect size varies from study to study.

- The two analyses sometimes produce exactly the same results, but often their results will differ. When this happens, either model can yield the higher estimate of the effect size.

Fixed-effect model

- The defining feature of the fixed-effect model is that all studies in the analysis share a common effect size.

-

⭐ The fixed-effect model starts with the assumption that all studies share a common effect size. If we start with that assumption, then the point of the analysis must be to estimate the common effect size.

-

For the fixed-effect model, the null hypothesis is that the common effect size is (for example) zero.

Random-effects model

-

The defining feature of the random-effects model is that there is a distribution of true effect sizes, and our goal is to estimate the mean of this distribution.

-

First, the confidence interval for the summary effect will always be wider under the random-effects model

-

Second, the study weights are more similar under the random-effects model (large studies lose influence while small studies gain influence)

-

-

⭐ The random-effects model allows that there may be a distribution of true effects. It follows that the first step in the analysis should be to estimate the amount of variation and then use this to inform the direction of the analysis.

- If the variation is trivial, then we would focus on reporting the mean and its confidence interval. If the variation is non trivial, then we might want to address the substantive implications of the variation, but the mean might still be useful as a summary measure.

- By contrast, if the variation is substantial, then we might want to shift our focus away from the mean and toward the dispersion itself.

-

For the random-effects model, the null hypothesis is that the mean effect size is (for example) zero.

Deriving the combined effect

Source of variance and inverse variance weights

-

The majority of meta-analyses assign weights to each study based on the inverse of the overall study error variance (that is, 1/variance). This provides a generic approach to meta-analysis that can be used to combine estimates of a large variety of metrics, including standardized mean differences, means differences, correlation coefficients, regression coefficients, odds ratios and simple means or proportions.

-

⭐ This scheme is used for both the fixed-effect and random-effects models. Where the models differ is in what we mean by a precise estimate, or (more correctly) how we define the overall study error variance.

-

For fixed-effect model this weight is given by

$$ W _i= \frac{1}{V_i} =\frac{1}{\sigma/n_i} $$ -

For random-effects model, this is given by

$$ W_i = \frac{1}{V_i + T^2}, $$where $V_i$ is the within-study error variance and $T = \text{var}(\alpha_i)$, is the variance of random effects or between-study variance

-

Computing the combined effect

-

The weighted mean (M) is computed as

$$ M = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^kW_iY_i}{\sum_{i=1}^k W_i} $$ -

Uncertainty in combined effect

$$ V_M = \frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^kW_i}, \text{SE}_M = \sqrt{V_M} $$-

Consider study weight as the information contributed by a study, then the sum of weights is the total information available to estimate M, and the higher this value, the lower the variance.

-

For fixed-effect model

$$ V_M = \frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^k\frac{n_i}{\sigma}} = \frac{\sigma}{\sum_{i=1}^kn_i} $$- If every study has the same sample size, $n$, then $V_M = \frac{\sigma^2}{k\times n}$; this is equivalent to pooling all the individual observations together for analysis

- ⭐ Importantly, because all studies are estimating the same value, it does not matter how the subjects are distributed across the studies. The variance of the combined effect will be the same regardless of whether we have 10 studies with 100 persons in each, 5 studies with 200 in each, or 1 study with 1000 persons, because the cumulative sample size is the same in all cases.

-

For random-effects model

$$ V_M = \frac{\sigma^2}{k\times n} +\frac{T^2}{k} $$assuming every study has the same sample size $n$.

- Note that the second term is analogous to $\sigma^2/n$, the formula for the variance of the sample mean in a primary study. In the primary study we were dealing with one mean and the observations were subjects. Here we are dealing with a grand mean and the observations are studies.

- The consequence of this second term in the variance of the combined effect (6) is that, if we have only a few studies, there is a limit to the precision with which we can estimate the grand mean, no matter how large the sample size in these studies. Only as $k$ approaches infinity will the impact of between-study variation approach zero.

- Namely, increasing the sample size within studies is not sufficient to reduce the standard error beyond a certain point (where that point is determined by $T^2$ and $k$). If there is only a small number of studies, then the standard error could still be substantial even if the total n is in the tens of thousands or higher.

-

Difference between the two models

- In fact, though, the estimate of the combined effect is almost always different under the two models (provided, of course that, $T^2$ is not zero).

- Because $T^2$ is a constant, it reduces the relative differences among the weights, which means that the relative weights assigned to each study are more balanced under the random-effects model than they are under the fixed-effect model.

- Concretely, if we move from fixed-effect weights to random-effects weights, large studies lose influence and small studies gain influence.

- While study weights are always more similar to each other when using random-effects weights as compared with fixed-effect weights, the extent of similarity will depend on the ratio of within-study error variance to between-studies variance.

- Note that the impact of $T^2$ on the relative weights does not depend on how many studies are included in the analysis, because the issue here is how much uncertainty $T^2$ adds to the effect size estimate in a specific study.

- By contrast, the precision of the combined effect (above) does depend on the number of studies because the issue there is how much information each study adds to this summary.

Which model to use when

-

It makes sense to use the fixed-effect model if two conditions are met.

- First, there is good reason to believe that all the studies are functionally identical.

- Second, our goal is to compute the common effect size, which would not be generalized beyond the (narrowly defined) population included in the analysis.

-

In the vast majority of meta-analyses the random-effects model would be the more appropriate choice

- is more likely to fit the actual sampling distribution;

- does not impose a restriction of a common effect size;

- yields the identical results as the fixed-effect model in the absence of heterogeneity;

- allows the conclusions to be generalized to a wider array of situations.

-

Caveats to using a random-effects model

- If the number of studies is very small, then the estimate of the between-studies variance ($\tau^2$) will have poor precision. In such case:

- Option A is to report the separate effects and not report a summary effect.

- Option B is to perform a fixed-effect analysis.

- Option C is to perform a Bayesian meta-analysis(?), where the estimate of $\tau^2$ is based on data from outside of the current set of studies.

- The second caveat is that, although we define a fixed-effect meta-analysis as assuming that every study has a common true effect size, some have argued that the fixed-effect method is valid without making this assumption.

- The third caveat is that a random-effects meta-analysis can be misleading if the assumed random distribution for the effect sizes across studies does not hold.

- The fourth caveat is that, as we move from fixed-effect weights to random-effects weights, large studies lose influence and small studies gain influence.

- If the number of studies is very small, then the estimate of the between-studies variance ($\tau^2$) will have poor precision. In such case:

-

Avoid mistakes when selecting a model

- Don’t use significance from the test of heterogeneity to decided if a random-effects model is preferred or not

- it is a bad idea to use a non-significant heterogeneity test as evidence that the studies share a common effect size as the test is often poor powered

- it uses fixed-effect as the default model, however the random-effects model is a better candidate for it as mathematically, the fixed-effect model is really a special case of the random-effects model with the additional constraint that all studies share a common effect size.

- there is no ‘cost’ to using the random-effects model as the impact from misspecification of the model when using random-effects model is minimal compared with fixed-effect model

- ⭐ Rather than start with either model as the default, one should select the model based on their understanding about whether or not the studies share a common effect size and on their goals in performing the analysis.

- Don’t use significance from the test of heterogeneity to decided if a random-effects model is preferred or not

-

weighting schemes

- Inverse-variance weights

- Mantel-Haenszel weights for binary data

- weighting by sample size for correlations

- They all assume that all studies in the analysis either share a common effect size (fixed-effect model) or are a random sample from a universe of potential studies (random-effects model).If either assumption is correct, then any weighting scheme will be unbiased.

-

Moderator variables

- If we expect that the variation in effect sizes is related to a continuous variable, we can use meta-regression to study this relationship. Again, we can apply either a fixed-effect or a random-effects variant of this approach, depending on whether or not we assume that all studies with the same covariate values will have the same true effect

References

Borenstein, Michael and Hedges, Larry V and Higgins, Julian PT and Rothstein, Hannah R (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. ↩︎