How R searches and finds stuff

by Suraj Gupta

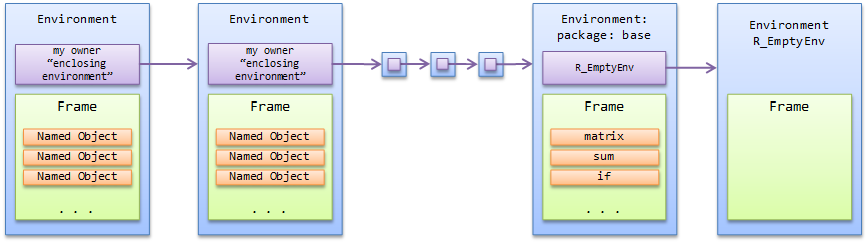

- Everything in R lives in an environment.

- Ultimately, we're trying to figure out which environment something lives in, and how we get there (or how we got there)

- An environment, like everything else in R is an object. Objects hold stuff. Environments are specialized, they can only hold two things:

- A frame

- This is just a collection of named objects. Since everything in R lives in an environment and the frame is the place where an environment holds objects

- Enclosing environment (environment's owner)

-

This is just a reference to another environment (parent environment).

-

The chain of enclosing environments stops at a special environment called the Empty Environment, which can be accessed with

emptyenv().

-

Given an environment object, you can query the object for the two things that matter: the environment’s owner and the objects in the frame.

-

- A frame

Play time with Environemnts

-

Create a new environment

> myEnvironment = new.env() > myEnvironment <environment: 0x0000000006ce0920> -

Every environment (except R_EmptyEnv) has an enclosure

> parent.env(myEnvironment) <environment: R_GlobalEnv> -

Who's R_GlobalEnv's enclosing environment?

> parent.env( parent.env( myEnvironment ) ) <environment: package:stats> attr(,"name") [1] "package:stats" attr(,"path") [1] "C:/R/R-2.14.1/library/stats" -

The

R_GlobalEnvmust be special if it can be retrieved using the identifier.GlobalEnvAND a functionglobalenv() -

The empty environment is accessed using

emptyenv()> emptyenv() <environment: R_EmptyEnv> -

<environment: 0x0000000006ce0920>is the location of the environment in memory. We can add a friendly name by assigning a "name" attribute.> attr( myEnvironment , "name" ) = "Cool Name" > myEnvironment <environment: 0x0000000006ce0920> attr(,"name") [1] "Cool Name" > environmentName( myEnvironment ) [1] "Cool Name" -

Unless you try hard, when you create an object it is automatically placed in the "current" or "local" environment, accessible using

environment(); And we can query an environment for all objects in the frame usingls(). -

We can override the default behavior and create an object in an environment other than the local environment using the

assign()function.> ls( envir = myEnvironment ) character(0) > assign( "myLogical" , c( FALSE , TRUE ) , envir = myEnvironment ) > ls( envir = myEnvironment ) [1] "myLogical" -

We can retrieve any named object from any given environment using the

get()function> get( "myLogical" , envir = myEnvironment ) [1] FALSE TRUE -

R uses the local environment as the default value. You can change an environment's enclosure using the replacement form of

parent.env().> myEnvironment2 = new.env() > parent.env( myEnvironment2 ) <environment: R_GlobalEnv> > parent.env( myEnvironment2 ) = myEnvironment > parent.env( myEnvironment2 ) <environment: 0x0000000006ce0920> attr(,"name") [1] "Cool Name" -

Another way to understand the "current" or "local" environment: We create a function that calls

environment()to query for the local environment. When R executes a function it automatically creates a new environment for that function. This is useful - variables/objects created inside the function will live in the new local environment. -

We call

Test()to verify this. We can see thatTest()does NOT printR_GlobalEnv. We didn't create any objects withinTest(). If we had, they would live in the0x0000000006ce9b58environment whileTest()is running. When the function completes executing, the environment dies.> Test = function() { print( environment() ) } > environment() <environment: R_GlobalEnv> > Test() <environment: 0x0000000006ce9b58>

Short Answer: How R Searches and Finds stuff

- It seems that environments are not just static repositories of objects. When R executes an expression, there is always one local or current environment. Maybe its easier to think of this as the active environment, in contrast to the other environments which are inactive. Or perhaps its more intuitive to think of an expression executing “within” a particular environment. The point here is that at any moment R can ask “hey, what’s the local environment.” R asks this questions a lot. In fact, it asks this question every time it needs to find a named object. We saw that R creates a new local environments every time it runs a function. So when we run any decently involved piece of code, functions call other function and environments spawn and die.

- When R goes searching for the names in that expression, it first looks at the objects within the local environment. If the object is not found by name in that environment, then R searches the enclosing environment of the local environment. If the object is not in the enclosure, then R searches the enclosure’s enclosure, and so on. That’s how R searches and finds stuff; it traverses the enclosing environments and stops at the first environment that contains the named object.

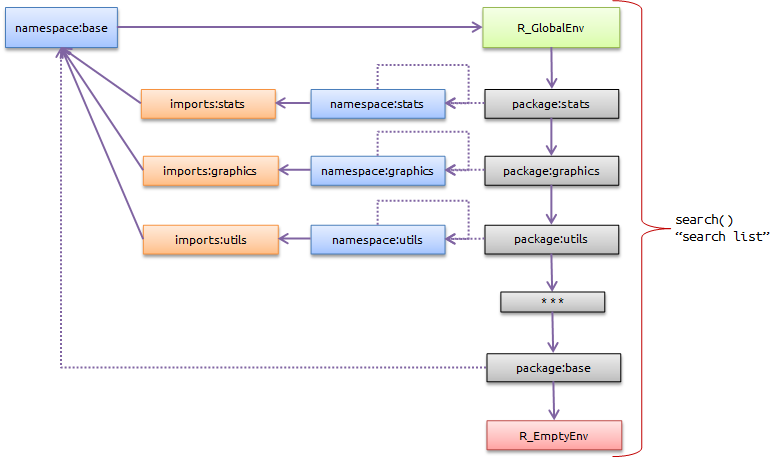

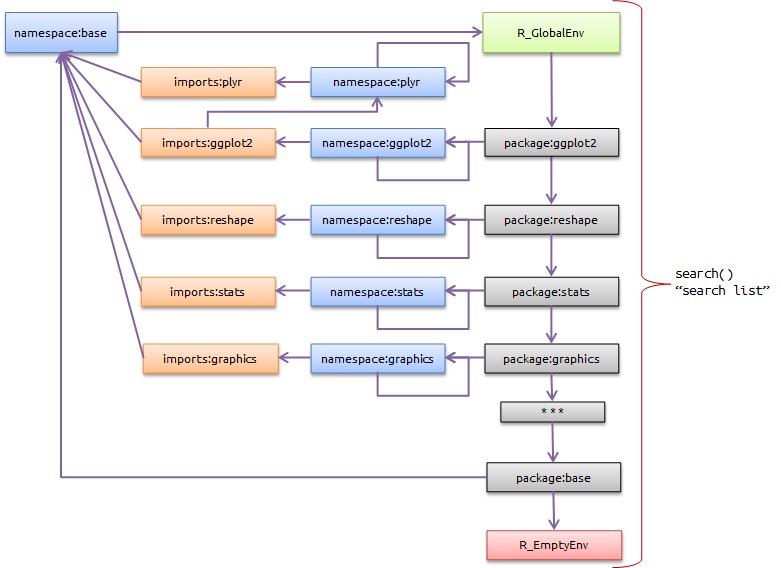

Map of the World (follow the purple line road)

This graphic shows the state of all environments when you first startup R. Each box represents a unique environment. The solid purple line represents the enclosing environment relationship. I’ll explain the dotted purple line in a bit. For now, consider it a relationship that’s similar to the enclosing environment.

The Global Environment

- The global environment is precisely the environment that you start at when you launch R. It is your current or local environment when R launches. If you make an assignment at the prompt, the named object is stored in

R_GlobalEnv. - Be careful with the

environment()function. It might seem wrong that this returnsNULLbut if you read the documentation you'll see thatenvironment()takes a function as input.myVariableis not a function, its a numeric. The purpose ofenvironment()is not to tell you an object's owner.

The Search List

- In R, the “search list” is the chain of enclosing environments starting with

R_GlobalEnvand ending withR_EmptyEnv. I like to think of it as the main highway on our map. This is the highway that R drives down when we start inR_GlobalEnv. All roads in our world eventually lead to this highway. You can obtain the search list by typingsearch()at the prompt:

Package v. Namespace v. Imports Environments

-

package environment

- This is where a package’s exported objects go.

- Simply put, these are the objects that the package author wants you to see. These are most likely functions.

- In traditional Object Oriented Programming (OOP), this is analogous to a “public” class or method.

-

namespace environment

- This is where all objects in a package go. This includes objects the package author wants you see. It also includes objects that are not meant to be accessed by the end-user[1]. In OOP this is analogous to a “private” or “internal” class or method.

- You might be thinking “wait, so objects the author wants me to see are in BOTH the package environment and the namespace environment?” Yes and No. Yes, both environments have a frame that lists objects of the same name, but no there is not two copies. Both environments have pointers to the same function.

-

imports environment

- This environment contains objects from other packages that are explicitly stated requirements for a package to work properly. Most packages published on CRAN are not islands; they build on functionality provided in other packages. The

imports:packageenvironment contains all objects in the imported packages.

- This environment contains objects from other packages that are explicitly stated requirements for a package to work properly. Most packages published on CRAN are not islands; they build on functionality provided in other packages. The

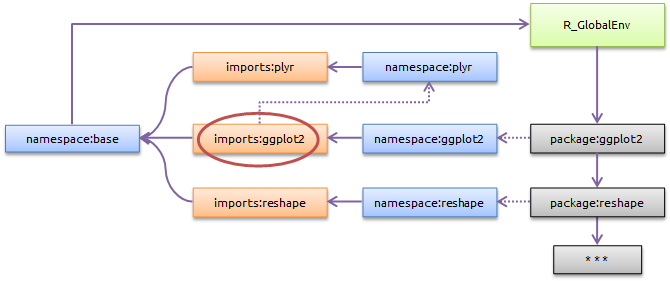

Imports v Depends

-

The

Dependssection also lists packages that a package requires.The difference betweenImportsandDependsis where the requirement is placed on our map of the world. Because our map specifies the path R takes to find objects, there are consequences to specifying a requirement inImportsversusDependsin terms of how R finds the dependency. -

If the package is specified in

Imports, then the package contents will go into the “imports” environment.-

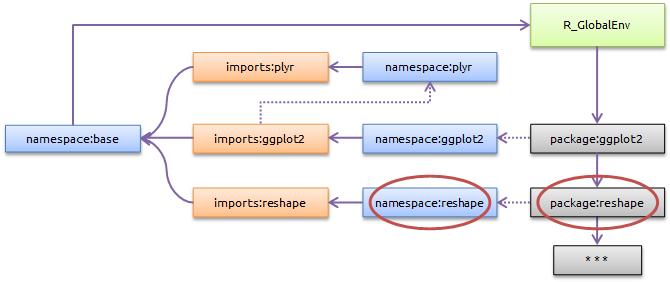

For example, In the case of ggplot2, the objects in the

plyrpackage will appear in theimports:ggplot2environment. Notice also thatplyrdoes not have a package environment. Its nicely tucked away inside the environmentimports:ggplot2.

-

-

If a package is specified in

Depends(i.e.reshapepackage), then the package is loaded as it would be if you calledlibrary()orrequire()from the R prompt. That is, the package, namespace, and imports environments are created for the dependency and placed on our map. The reshape package is attached beforeggplot2and thepackage:reshapeenvironment becomespackage:ggplot2’s enclosing environment.

-

Is the choice between Depends and Imports arbitrary? Its not. The

library()command (or generally attaching a library) places the package environment underR_Global. More precisely, the package environment becomesR_Global’s enclosing environment.R_Global’s old enclosure now encloses the package environment.

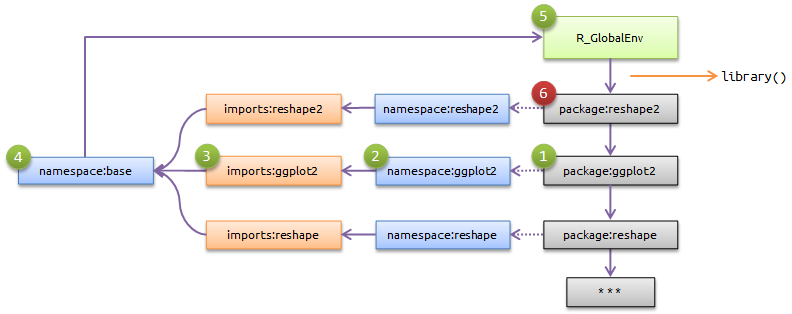

- Both

reshapeandreshape2contain the functioncast. Lets say (I’m making this up) thatggplot2has a function calledFunctionThatCallsCast(). As you can guess, this function calls thecast()function. Without knowing any details of how R finds stuff, lets just follow the “purple line road”. We travel from to 1 and 2 and findFunctionThatCallsCast(). Remember, the package and namespace environments both reference a package’s public-facing functions. We execute that function and now we need to findcast. We travel from 3 to 5 searching forcast. We findcastat 6 and stop. But this is the wrongcast. This iscastin packagereshape2, butggplotdepends on thecastinreshape. This could have dire consequences depending on the differences betweencastinreshapeandreshape2. - The better solution would have been to stuff

reshape’scast()function intoimports:ggplot2using theImportsfeature. In that case, we would have travelled from 2 to 3 and stopped. Now you can see why the choice betweenImportsandDependsis not arbitrary. With so many packages on CRAN and so many of us working in related disciplines its no surprise that same-named functions appear in multiple packages.Dependsis less safe.Dependsmakes a package vulnerable to whatever other packages are loaded by the user.

- Both

namespace:base

- All

imports:<name>environments havenamespace:baseas their enclosure. Think of this a freebie for creating a package. Since the base functions are used frequently, they are most likely a dependency for any package (or a package’s imports). Withoutnamespace:basewhere it is, R would have to go hunting quite far to findpackage:base. There’s a big risk that another package has a function of the same name as a base function. - A package author cannot know a-prior when you intend to attach her package nor that you have decided to write your own version of a base function. So do as you like, a package author can expect that R will find the base functions immediately after

Imports. There’s no chance of corruption.

The Curveball (the dotted purple lines)

-

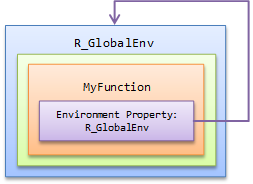

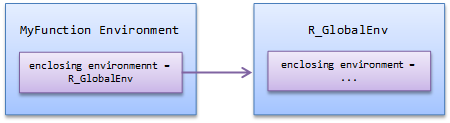

Functions, like all objects, are housed inside environments. However, functions themselves have a property which is a pointer to the environment in which they should run. When you create a function, that property is automatically set to the environment in which the function was created. So the environment that houses a function and the environment that the function will run in is one and the same.

-

"The environment that a function will run in": executing a function creates a new environment specifically for that function and the enclosing environment function’s new environment is what is specified by the function’s environment property. This is “the environment that a function will run in.” We can get a function object’s environment property using the

environment()function.> MyFunction = function() {} > environment( MyFunction ) <environment: R_GlobalEnv> -

And when we run

MyFunction()and R is executing lines of codes inside that function, the environments look like this:

-

By default, R sets a function’s environment property equal to the environment where the function was created (the environment that owns the function). However, its not necessary that a function’s executing environment and the environment that owns the function are one and the same. In fact, we can change the environment to our liking:

# notice how environment(MyFunction) no longer returns R_GlobalEnv > MyFunction = function() { } > newEnvironment = new.env() > environment( MyFunction ) = newEnvironment > environment( MyFunction ) <environment: 0x000000000e895628> -

Another way to see a function's environment property is to just print the function. The environment will appear at the bottom of the printed function.

-

How R searches for variables in a function call: find the "cloest" one to use first if not otherwise specifically specified for its enclosing environment

> age = 32 > MyFunction = function() + { + age = 22 + FromLocal = function() { print( age + 1 ) } + FromGlobal = function() { print( age + 1 ) } + NoSearch = function() { age = 11; print( age + 1 ) } + environment( FromGlobal ) = .GlobalEnv + FromLocal() + FromGlobal() + NoSearch() + } > MyFunction() [1] 23 [1] 33 [1] 12 -

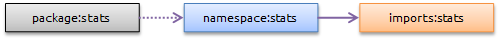

This explains the dotted purple lines in our map. If you inspect the environment property of the functions within the

package:<name>environments you’ll see that they all point to thenamespace:<name> environment. So in essence, the package environment is just a pass-thru to the namespace environment.> statsPackageEnv = as.environment( "package:stats" ) > sdFunc = get( "sd" , envir = statsPackageEnv ) > environment( sdFunc ) <environment: namespace:stats> > statsNamespaceEnv = environment( sdFunc ) > sdFunc2 = get( "sd" , envir = statsNamespaceEnv ) > environment( sdFunc2 ) <environment: namespace:stats> # An easier way to get a namespace environment > statsNamespaceEnv = asNamespace( "stats" ) > statsNamespaceEnv <environment: namespace:stats> -

The package environment says “I don’t know what to do, ask my functions”. And when we ask the functions they all say “when you execute us create a new environment whose enclosure is the namespace environment.” More precisely, the functions are just offering up their environment property . We might as well make those dotted lines solid:

-

Incidentally, this is another explanation for why there’s no easy way to query an object for the environment that owns it. When we are executing in an environment, we are interested in the objects it owns because we might be looking for one of them. When we find a function we need to know which environment to execute it within. But its not important in our workflow to identify an arbitrary object’s owning environment.

Passing Functions

- If a function

FunctionA( someOtherFunction )takes another functionsomeOtherFunctionas a parameter thenFunctionAmust have some variability in the way it runs. That variability is governed by the implementation ofsomeOtherFunction. When we constructsomeOtherFunction, we expect it to run in a particular way.someOtherFunctionshould have access to the objects in the environment in which it was constructed. That expectation doesn’t change when the function is handed-off toFunctionA. But R creates a new environment forFunctionA. Thankfully that’s not a problem. WhensomeOtherFunctionis finally run R looks to the function’s environment property and executes within that environment, not withinFunctionA’s environment. So the integrity of our expectation is upheld. In fact,FunctionAcan passsomeOtherFunctiontoFunctionBwhich in turn can pass the function toFunctionCand it has no consequence on howsomeOtherFunctionwill run. That’s the magic of a function’s environment property.

That Creepy Caller

- The call stack is the sequence of function calls that has gotten you to wherever you currently are in the calculation. For example,

FunctionAcallsFunctionBwhich in turn callsFunctionC. The call stack just places each of those functions on top of one another in the order in which they were called. Lets sayFunctionCneeds to executeFunctionD. The wrong way to think about the search mechanism is to follow the callers. - Unfortunately, the call stack is more intuitive than the chain of enclosing environments. Just remember, whenever R is evaluating a statement the system is simultaneously at the top (or bottom if it’s easier to visualize that way) of two important chains of environments.

- One is the chain of enclosing environments which is involved in the task of scoping (i.e. where to look next for variable names not found in the frame of the current environment). This is the chain we care about.

- The other chain is the call stack, which is produced by the sequence of function calls. You can ignore this chain.

- There are scenarios where it’s necessary to look for a variable via the call stack, but to accomplish that you have to use some special functions in R.

- A word of caution: R (and some R literature) uses the term “parent” in context of both chains. There’s the function

parent.env()which we already know andparent.frame()which is used to interrogate the call stack. This is certainly confusing and its a historic slip-up. The term “parent” should not be used as a substitute for enclosing environments. It should only be used with the call stack.

Finally, How R searches and finds stuff

- R just follows the purple line road in our map above.

- If

ggplotis not in the global environment, then it must be in a package. So R travels down the search list looking forggplot. This is simply the chain of enclosing environments starting withR_Global. R ultimately find the function in one of the package environments. Althoughggplotis found within thepackageenvironment, R executesggplotwithin thenamespaceenvironment as described in the prior section. In this case, we’ve foundggplotinpackage:ggplot2and we execute the function withinnamespace:ggplot2. - Lets say

ggplotcalls another functionMyFunction. A few things can happen:- If

MyFunctionis defined withinggplot, then we find it immediately since R checks the local environment first. In this case the local environment is the environment created to runggplot - If not found, then R looks to the enclosing environment of

MyFunction’s executing environment which isnamespace:ggplot2. If we findMyFunctionhere, then it’s a case of a package function calling another function in the same package. - If

MyFunctionis not in thenamespace:ggplot2, then R checks the enclosing environment of the namespace environment which is the imports environment. This givesggplotan opportunity to findMyFunctionwithin a set of explicitly defined package dependencies. This is like ggplot finding a plyr function in our example above. - If

MyFunctionis not in the imports environment, then we check the enclosing environment of the imports environment which isnamespace:base. A base function (i.e. sd() for standard deviation) would be found here and the search would be complete. - If

MyFunctionis not found innamespace:base, then we are back to the search list. We start by checkingR_GlobalEnv. Its unlikely thatMyFunctionis inR_GlobalEnv. It would be poor practice for a package to expect the user to define some function in the global environment. However, the user could take this as an opportunity to intercept the search by defining her own version ofMyFunctionin the global environment. - If

MyFunctionis within a package that’s a dependency ofggplot2and that dependency is specified inDependsrather thanImports, then the search list is where we would findMyFunction.

- If

Qualitative Comments

- If we are executing outside of a package (as in

R_GlobalEnv) it enables us to find functions inside packages. If we are inside a package it allows the package functions to find the specified dependencies. If we are inside a package or a package’s imports (dependencies), then we have a buffer of base functions before we plunging into the search list. Also, the design ensures that we terminate atR_EmptyEnvif a named object cannot be found, no matter where on the map we are.

Skip the search-and-find

-

f you know exactly which package contains the object desired then you can reference it directly using the

::operator. Simply place the package name before the operator and the name of the object after the operator to retrieve it. -

If the object is not exported or you are unsure, then you can use the

:::operator (notice the extra colon).-

This operator searches the namespace environment for the given object (as we discussed, non-exported objects do not appear in the package environment, only in the namespace environment).

# view the ::: operator function > `:::` function (pkg, name) { pkg <- as.character(substitute(pkg)) name <- as.character(substitute(name)) get(name, envir = asNamespace(pkg), inherits = FALSE) } <bytecode: 00000000073BAEA8> <environment: namespace:base>

-

The latter, the “hidden” objects (they are not really hidden, you can access them if you’d like) facilitate the “visible” ones. ↩︎